They prefer a video call over a list of typed questions to avoid the “pretence” which creeps into writing and is absent in one-on-one chats. Back against an exposed red brick wall and the Amsterdam sun shining in their eyes, squinting and sniffling, Rah apologises for having a cold. Their body of work, available in the Mumbai-based TARQ gallery, their website, social media, and articles covering exhibitions, are intimidating. But the artist, with their slight frame and soft voice, is not. Exuding warmth, Rah says they “do not like having conversations not rooted in anything”. I ask if they feel at a disadvantage during interactions with strangers, since the personal nature of their art means that more about them is known than can be known otherwise. “There is this parasocial relationship based upon the perception of a curated image. But you don’t know me. As much as things are presented to look a certain way, I am very different from the expectations,” they say.

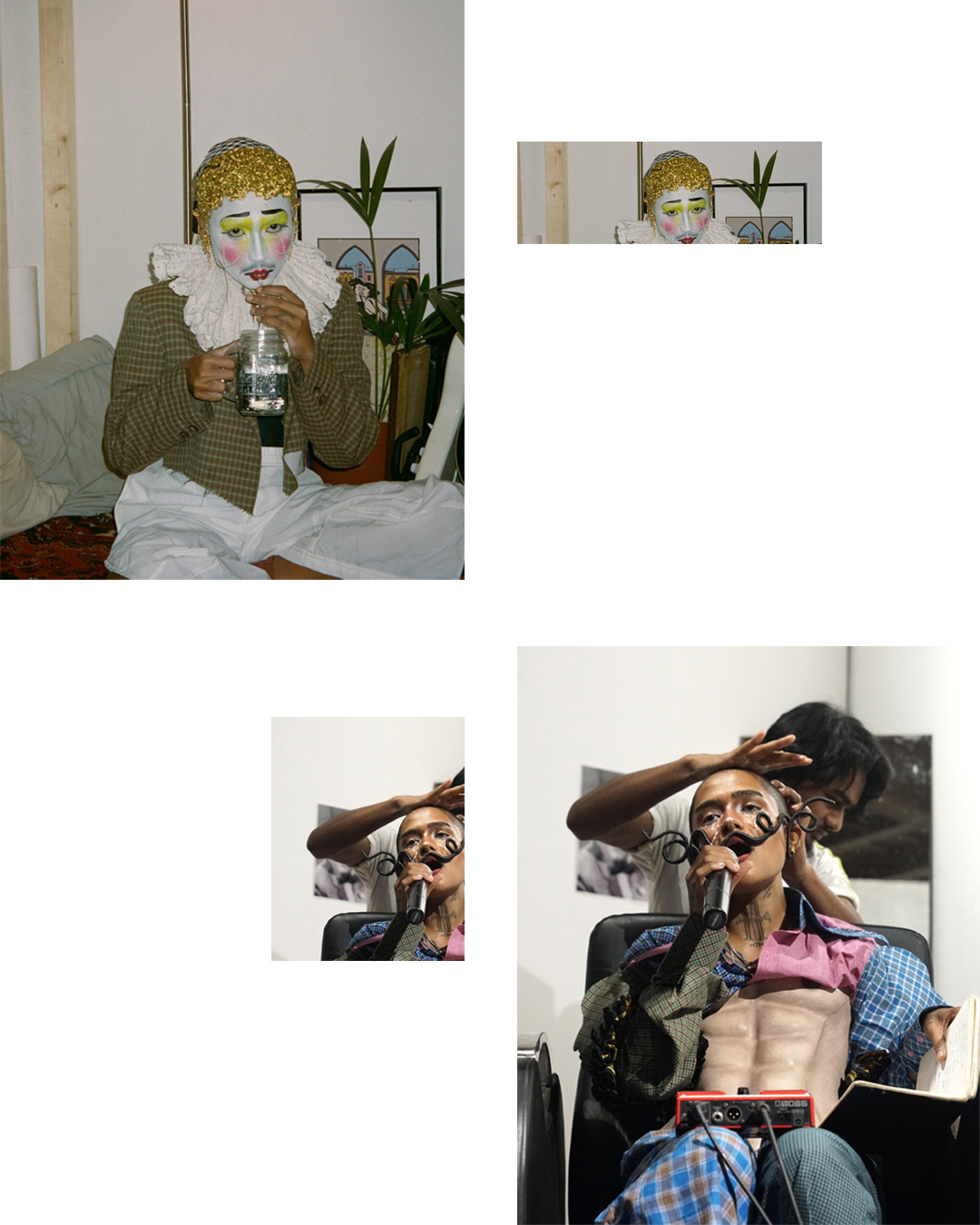

Rah Naqvi and the work that goes into ‘making’ and ‘being’ art. Photographed by Beatriz Lerer Catelo.

Rah has lived many lives in many places; a childhood in Mumbai’s Mira Road, summer vacations at Nanna’s home in Aligarh, graduation years at St. Xavier’s Mumbai and Ahmedabad’s National Institute of Design (NID), a brief stint at setting up a studio in Darjeeling with friends, and finally the big leap, a residency at Forecast Forum in Berlin which in turn brought them to Amsterdam via the De Ateliers Residency. Their art chronicles these organic and often tectonic shifts of geography and identity. They tell me, “The nature of work changes in accordance with where it is being presented. I am changing, growing, and my work grows with it.”

What is your motivation behind your nostalgic pieces, for instance A Bed Not Big Enough and Shanakht? “It is less about the past rather the innocence and naivety of being so young. Even if I am speaking of my mother or grandmother in my work it is their story but their story exists within a larger discourse. It boils my blood to see people who have nothing to do with our community or lives, in the name of upliftment, be exploitative. They take a bunch of pictures of women in Shaheen Bagh, monetise the temporal appeal of these resisting figures, and their labour, while our communities battle the same struggles as before. The ones you demonise and ostracise as women with no power, are the ones fighting for our collective rights.” Their Blanket of Solidarity is homage to the movement. Rah’s maternal family lives in Shaheen Bagh, so the events which began unfolding in December of 2019 must have carried personal stakes? “It was not just the pain and fear of the fact that something as draconian as that law could be passed. My Appi was studying at Jamia, she was at the protest and she got hurt. Amidst the distrust, I had to find a community in the Netherlands to fight and amplify what was happening.” Could they maintain momentum in Amsterdam? “For a while. There is a neglect when it comes to how much attention the global community offers to South Asian issues. Value is based on global positioning, skin colour, etc.”

In performance, Rah Naqvi. (Top) White Man Weeping, photographed by Beatriz Lerer Castelo; (Bottom) Soft Touch Men, photographed by Shivani Gupta.

So how did the move to Amsterdam happen? “I had never imagined that this could be a possibility when I was studying in NID, Ahmedabad. But in my second year, I knew in my bones that I could not continue working in textile because it is a very exploitative industry. [While] working with artisans, you see that their lives never change while you keep progressing. I knew that I had to be an artist. Lekin hamare ghar mein kaun artist banta hai? (But who becomes an artist in our home?)” This is a universal experience for middle class kids of the ’80s and ’90s. The idea that humanities and fine arts can get you a career and money is emerging now, back then it was inconceivable. “But it is not the same here (Amsterdam). The access to art is very different from how it is back home.” It does not take too long to figure out why that is. The resistance is borne out of simple, human, survival instinct. “Yeah, these people have safety nets. You start from a point which is relatively alright. I started doing a lot of research to find open calls that I could apply to. To my surprise I got into a short term residency in Berlin. From there I went to Amsterdam for a day and visited De Ateliers. When I saw this place my mind was pretty blown.” What was the setup offering? “The thing that I saw first was enormous, absolutely massive spaces. Space itself screamed of stability. It was a desire to have a place where I could just do my work without restraint. So I decided to apply. After sending this application, a lifelong imposter syndrome made it seem unlikely that I would get in. It was also around this time that I started a design studio with my close friends from college in Darjeeling.” This is where Rah’s journey gets tricky. They were confronted by the nexus between capitalism and art. “We had meagre savings, but endless resources in the form of collective hope.” Can anyone break into these spaces without being backed by capital? “I will genuinely be very honest. Caste and class will give you this advantage and privilege that most people don’t like to recognise and acknowledge because it reveals that talent has other things to credit for its success. It has never been an even playing field. Even speaking English. The language automatically makes these ‘open calls’ available to you. Acknowledging it is a very small step.” As a trans person, who is South Asian and Muslim, but also middle class and conversant in a first world language, Rah has no qualms about admitting the advantage they may have over many others. “There is power in me coming from a family which has a roof over their head. India is a place that provides you with ample opportunity to realise what class and caste position you are in. If you cannot do that work and still decide to perform victimhood, both in India and in the west, then you are contributing to a serious problem.”

Has the struggle in their practice, especially as an early-to-mid career artist, ended or eased? “If it comes to my practice and its development, then I would consider myself ‘Oh! Mid-career’. But, financially I am still struggling.” The way Rah says it makes it sound that opportunities are scarce when in reality their principled rejection of collaborations and talk about your associations are a big reason behind this. “When you talk about the art world and opportunities, so many people are exposed as agents of capitalism based on what they have continued to say yes to. That has been a complete eye opener.” It reminds one of Khalil Gibran’s “Tum zulm ke khilaaf kaise naara lagaoge, tumhare munh mein toh niwala hai (How can you raise your voice against injustice when your mouth is full of food?”). Rah brings back the trope of the ‘broke’ good artist. ‘Good’ in their case signalling to both art and ethics. Did they feel the pressure to have a side gig? “Yeah, I do hand-poked tattoos for people to make some extra money but working from precarity just doesn’t feel romantic at all.” What is one to do? Today, how we make money is how we individuate ourselves. “That is sad, isn’t it?”

Rah Naqvi for ‘Soft Touch Men’. Photographed by Shivani Gupta.

They were mentioned in Forbes 30 Under 30, as people “who could not be ignored”. Do moments like that spell success to them? “I don’t consider that as success. Names are used without knowledge or consent but no one is there to support your practice. These supposed lists are of no use to me.” Is it so hard to find alternative spaces that align with their values within India? “Nothing good comes out of my mouth regarding the art world. I have tried to the best of my ability and capacity to reject opportunities which have blood money tied to them.” They could write a Bourdain style ‘Galleries Confidential’. They laugh, “Yes. I could. Sometimes I wish I did not see so much in black and white and see grey areas that most do. I don’t create for the sake of creating. I feel deeply that it is a great privilege to have skill and opportunity, so I must do justice to that.” Do they think age will temper this ‘absolute-ness’ of morality? “I doubt it. I think it is an autism thing as well. There is a sensitivity which makes things so blatantly clear that it is hard to look away.”

People and places figure so significantly in their art, do they ever consider moving back to the country? “When I first came here the goal was to come back but I worry for my safety, about the repercussions visibility would bring. My family is supportive and understanding mostly because I am outside the peripheries of control. At home they were very afraid for their own safety and mine. I used to work in my parent’s living room for the longest time. I loved it! Not complaining. But while I worked there, they insisted on me toning down my work for very valid concerns and fears.” Trans rights in India have been called inadequate by human rights organisations for some time now. The medical stipulation attached to being recognised as the gender a trans person identifies with has a strong element of coercion to it. Even at the level of culture, people are not accepting of these identities. It takes on violent forms of abuse, threats, and in some cases, assault with impunity. “When I think about coming home I want to first feel secure. The only commitment I have is to people and their lives. I don’t think that I have a deep, dying love for the nation state. Why must one have pride for a nation state which is murdering and brutalising its people?” Do they feel there are spaces in Amsterdam where a similar threat exists? “Yes and unfortunately they are very well organised! In the name of celebrating culture and dance, many upper caste nationalistic organisations in the west operate under a facade that sustains the funnelling of funds to right wing organisations in India. The imperial core is generally so disinterested in our socio-political issues that they rely on these superficial celebrations to educate themselves.”

Rah is not aiming for mainstream success but their community is growing with every piece, medium, and cause. “There are a lot of things that influence me. Your work is an embodiment of your journey, the things you learn, the people you meet. Everything is a process. It is how we create spaces for conversations and leave behind the knowledge we have gained for the next person. If it has to have that longevity then it needs to be a very patient process and a selfless one.”

Words by Ayesha Suhail.

Feature photo by Shivani Gupta.