The first thing we imagine when we think of Ladakh are the mighty mountains, the clear skies, the surreal culture, and the unique nature of native settlements. However, we wanted to engage further with some of the contemporary developments in the Ladakhi region, from the last few years, to understand more about Ladakh’s nomadic architecture and the many, visible pressures placed on Ladakh’s landscape by haphazard urbanisation, growing foreign investment, among other things.

The dramatic scenery of the region is characterised by temperamental climatic shifts and colourful bands of diverse sediments.

That’s when we found Oorvi. Oorvi is a practising architect, independent researcher, and writer who works at the confluence of social and ecological dimensions of architecture, urban planning, and urban design. She is the founder of project NORSOU, a creative and research-led platform for the production of cities, landscapes, policy tools, and ideas. Her work as an architect is grounded in the belief that the practical applications of architecture should address the needs and goals involved in enhancing the everyday lives of citizens through spatial applications and context-specific conversations about contemporisation.

These are aimed towards the health of local populations, economies, and carefully-considered, natural environments. She wrote a piece titled ‘Inverted Grounds; Tethered Geographies’ that explores the built landscape of Ladakh, and, in Oorvi’s words, “explores the impact of recent, cumulative forces on regional, homegrown architecture, which are under threat of broad-brush, homogenous solutions/high-tech homogeneity”.

Oorvi Sharma

Her essay focuses on how recent constitutional change, particularly the 2019 abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A, affects Ladakh’s indigenous, earthen construction practices and the related socio-political landscape of regional development. While this scenario of analysis focuses on contemporary contexts in the region of Ladakh, her essay applies to a range of global communities which currently face similar conditions. Comprehensive and detailed, Oorvi’s essay is a textual, knowledge-based, interdisciplinary collage that weaves together concepts of architecture, urban planning and legal discourse. The essay is also grounded in Oorvi’s direct, regional field-experience, and evaluates the Ladakhi scenario through the lens of promoting the health of locally built environments and processes.

Sharma believes that thoughtful architectural practice and discourse can serve the purpose of sociopolitical advocacy, and vice versa. In her own words, foundational to her work is, “the belief that spaces, communities, and regions can be conceptualised, designed, and built differently in order to transfigure, support, and transmute local ecologies without financial or expressive compromise.”

During our interview with her, some very interesting conversations emerged that shed light on some of Ladakh’s unique architectural characteristics, along with the threats the region faces today.

Avantika Mishra: Your work brings attention to the essentials in the way buildings are designed and constructed. What are the existing essentials for designers and developers to consider in the context of Ladakh?

Oorvi Sharma: Ladakh is host to a unique mix of geographic, climatic, fuel, and resource conditions. The compounded effects of freezing temperatures in the winter and powerful heat from a scorching summer sun, when combined with the region’s extraordinarily dry air, render an entirely unique relationship between Ladakh’s locals and regional architecture. There was always a culture of building local villages, homes, and monasteries from soil that was sourced and fabricated on-site.

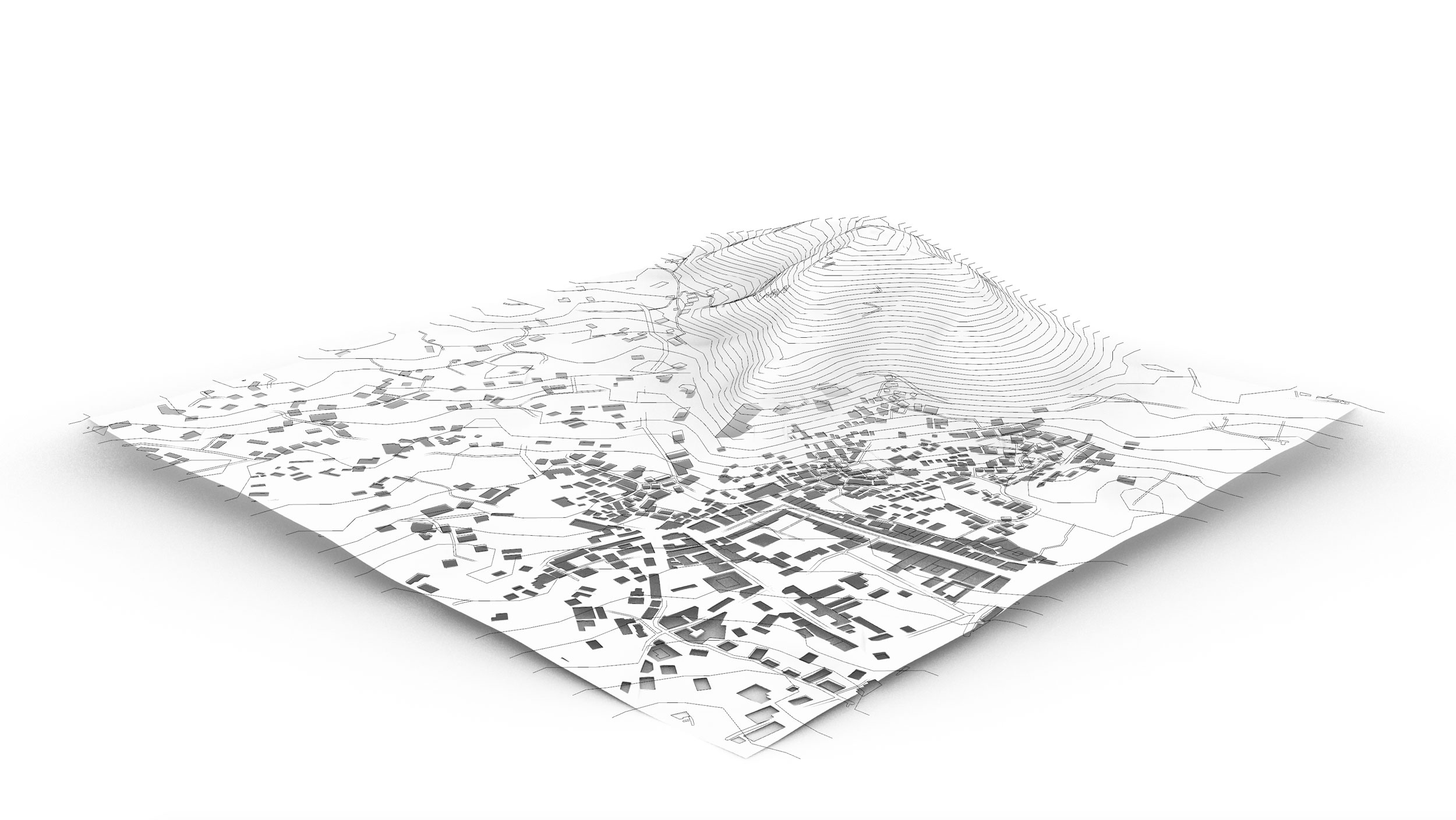

Topography of Ladakh in different seasons.

OS: In many ways, Ladakh is a sedimentary paradise, due to a convergence of the Himalayan orogen, numerous lakes and the valleys of the Indus, Zanskar, Shyok and Suru rivers. Thus. soil composition historically precipitated two primary building techniques in Ladakh: rammed earth and sun-dried mud bricks, the latter of which is more prevalent. These bricks and rammed walls were almost exclusively unstabilised, meaning they were made without cement. The mass of these walls, often supported by raw stone foundations, captured heat during the day, gradually warming interiors throughout the evening. Openings in earthen walls were strategic, to provide natural light where needed, while minimising unwanted heat transfer.

As a result, Ladakh’s vernacular architecture and indigenous construction dialogue is thermally-informed and ecologically-minded at its core. There is also an embedded ethical dimension to this regional, vernacular approach. By using fewer resources, the carbon footprint is relatively lower. In addition, using earth to build in an area where the material is readily available, inevitably saves money and time.

A narrow alleyway in Leh’s old town.

AM: How can contemporary attitudes to the accelerated construction in the region respond to these indigenous values of building with the existing ecologies in mind?

OS: Designers are problem solvers however, when faced with the depths of current issues in our cities and communities, we reach for tools with which we are generally familiar. This is why there is an absolute need, regionally and nationally, for radical, disciplinary retooling that resists superficial, greenwashing rhetoric and haphazard, accelerated development.

In this current period, fuel and energy consumption and carbon emissions are key issues. Especially in Ladakh, it is imperative to question whether we actually need any cement or concrete at all, and what form that might take as a spatial tectonic, in detail, and as an aesthetic matter.

Specifically for the region, designers should be developing an evolved architectural language suited specifically for Ladakh’s climate, where contemporary construction is rethought with local ecologies, emblematic ambitions, and extant resource realities in mind. The way forward is through retooling of the production process wherein a genuine, ground-up consideration of program, siting, materiality, and operational interaction produces solutions that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Children play on a terrace, amidst a group of clustered, earthen dwellings in Thiksey village.

AM: What are your views on current development paradigms in the region given the ongoing protests?

OS: The continued political and legal pressures on the Ladakhi community are palpable, as they seek to preserve their rights, livelihoods, and regional ecologies. As a result, there is merit in the current 2023 organisation of protests and local demands to include the region in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution with the aim of achieving constitutional support in the safeguarding of existing ecologies, microeconomics, and populations.

Ladakh is at risk of serving a perceived role of the hinterland, as ontologically and spatially divergent from the metropolis – and in turn, adopting subservience to industrial extractive capital. In response, over and above regional economic goals that are geared towards tourism-related densification and investment attraction, there is a real need to acknowledge socially responsible and ecological objectives in Ladakh. Specifically for architects in the region, there should be a concerted effort to develop a site-specific architectural language, evolved spatial and material tectonics, and innovative engineering solutions that are suited specifically for Ladakh’s climate. Construction should be rethought with local ecologies and extant resource realities.

Left: A small congregation of monks gathered beneath the smoke holes (tokskya) of the winter kitchen (rgyamthong) at Hemis Monastery.

Right: A range of restored domestic and religious structures that exhibit traditional techniques of building with mud-brick and local timber can be found in the region.

AM: In addition to the recalibration of design paradigms, what kinds of building policy implications are needed in response to regional and environmental needs in Ladakh?

OS: There are vast opportunities for policy intervention in the region which require local political entities and organisations to invite local populations to engage further as they imagine futures for the region. These efforts require the collective, active engagement with, interalia, regional experts, adept law-makers and architects, and citizens with a historical, contextual stake.

Looking beyond the adoption of Western-centric solutions, there is a need to strategise on how the disparate regions on the planet are developed or address the effects of climate change. Furthermore, it is time to take cues from the lack of resolution of the polarised debate between the Group of 77 (now 134) and Western countries regarding the effects of inequitable consumption distribution and resultant repercussions that should be shouldered by those responsible in order to compensate for damages, while not limiting what is needed for some to meet established levels of development and prosperity.

Words by Avantika Mishra.

Photographs by Oorvi Sharma.