A blend of cultural conditioning and sheer pragmatism enable Japanese family businesses to last for centuries – all while deflecting sticky-baton situations, father-son conflicts and the silver spoon syndrome. One such story is of the Kikkoman family.

Kikkoman, a Japanese company with over 2,000 products, an annual turnover of over US$ 40 billion and an impressive worldwide presence grew out of a deceptively simple sauce that was once thought of as ‘salty and one dimensional’. Made from four natural ingredients – water, soybeans, wheat and salt, their secret brewing process has remained unchanged for centuries and is called the Honjozo method.

Today, Kikkoman is the largest manufacturer of soy sauce in the world and the Imperial family’s preferred brand as well. Through their innovative marketing approach, they hope to be a staple in every kitchen in India by targeting “one restaurant and one self-taught chef at a time”, says Harry Hakuei Kosato, the Ivy League-educated, social entrepreneurial face of Kikkoman India.

Illustration of soy sauce brewing deposited at the Noda City Museum.

It all began in Nodu, a little Japanese town just north of Tokyo when the Mogi family set up a brewery in their farming community along the Edo river. In 1917, seven soy makers formally decided to join them and formed a company called Noda Shoyu. Renamed Kikkoman in 1964, it became a serious global player after World War II, when the occupation forces and hundreds of journalists who had been in Japan sparked a Western fascination with Japanese cuisine. The Kikkoman top brass saw the glimmer of opportunity and following their instincts, entered the American market with a bang (and shrewd marketing plan), opening their first overseas sales base in San Francisco in 1957.

Today, nearly twenty generations later, their descendants run three soy sauce production plants in Japan and seven overseas, while enthusiastically expanding their market share worldwide.

However, the question remains – in a rapidly changing scenario where economic disruptions are the norm, how have Japanese companies like Kikkoman found a way to survive and thrive over centuries while keeping the family business ethos intact? According to the Research Institute for Centennial Management, over 52,000 companies in Japan are at least a hundred years old – many spanning multiple centuries. Kikkoman, for example, has over 350 years of history and production facilities in Japan, the United States, Singapore, Taiwan, China and the Netherlands, all while still operating as a family business.

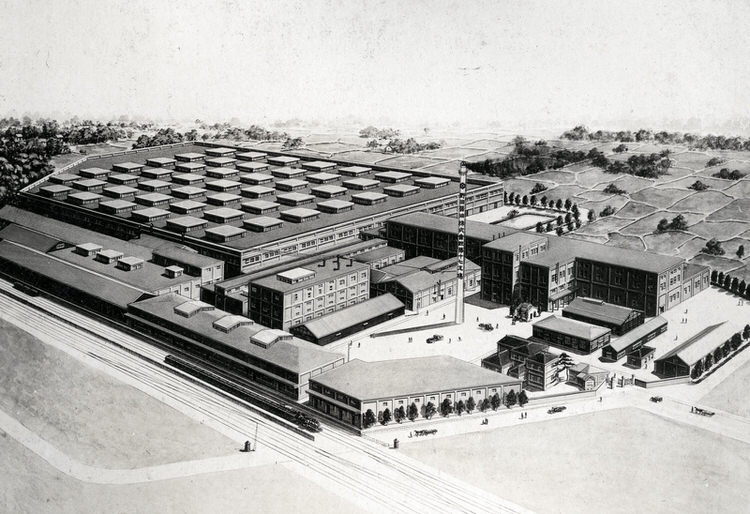

The Osaka Office in the early 20th century. (Top)

A birds eye view of Plant No.17. (Bottom)

“The Japanese social value system is very unique, entailing strong cultic features and a tough corporate identity that is an integral part of daily life. It has defined the nature of Japanese society since the Edo period with the ‘Ie’ system at the core of every traditional Japanese family. The term ‘Ie’ literally translates to a household and refers to a multigenerational family system where only one child inherits and the others have to fend for themselves. The Ie is intended to last forever and in principle never die. Japanese culture plays down the role of the individual and places importance on conformity and the success of the group as a whole instead – Shintoist values, harmony, horizontal ties, and an egalitarian structure are always emphasised. It functions as a corporate body that holds property in perpetuity. The Chairman and head of the Ie is in full control and the family is programmed to support him in every possible way,” explains Harry San.

Osamu Mogi, Head of International Operations Division at Kikkoman Corporation, whose family began to produce soy sauce in the 17th century, adds, “The secret of our success is quite simple. With a history spanning over 350 years and rooted in Japan, we have kept strictly to our family rules. Each generation may only have one member of the family enter the Kikkoman business, and there is no guarantee that a family member will join the board just by virtue of birth.”

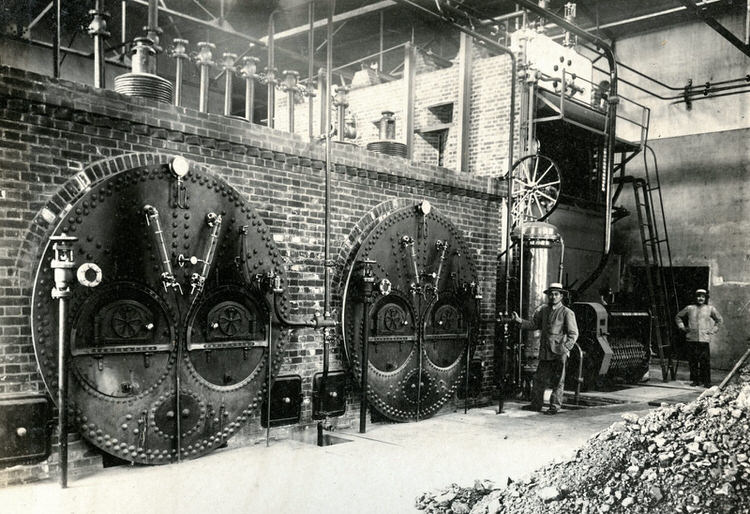

The Boiler Room of Plant No.17

Harry-san further explains that in order to keep lineage effectively controlled and prevent company assets from splitting up, “the Ie passes on the reins of the company to a suitable successor who is most qualified to ensure the survival of the company, not necessarily a first born son or blood relative. In case the Ie has no children, or they are incapable of taking charge, an outsider can be roped in to fill the role through adoption. This age-old adult adoption practice in Japan was developed so that families could successfully extend their family name, estate and ancestry without an unhealthy dependence on bloodlines.”

Apparently this system motivates the descendents to do a good job or risk being sidelined by a rank outsider and gives capable employees a chance at becoming an official part of the family themselves.

So how does Kikkoman successfully capture new markets?

“In 1949, after being listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, our company continued to put emphasis on governance, and now has a structure of appointing internal auditors. In 1957, we executed a full-scale entry into the U.S. on the heels of the American forces who paved our way. In 1972, the decision was made to set up a U.S. plant, by the then president from one of the founding families. Kikkoman’s global business subsequently turned profitable, and has grown now to comprise 70 per cent of the group’s revenue, and deliver 77 percent of the group’s profit. We later expanded into Europe, Asia and South America. In 1961, we created a teriyaki sauce that went remarkably well with barbecues and we taught Americans that the flavours of Kikkoman could enhance familiar foods like meat marinades, burgers, roasts, stews and casseroles,” says Osamu-san.

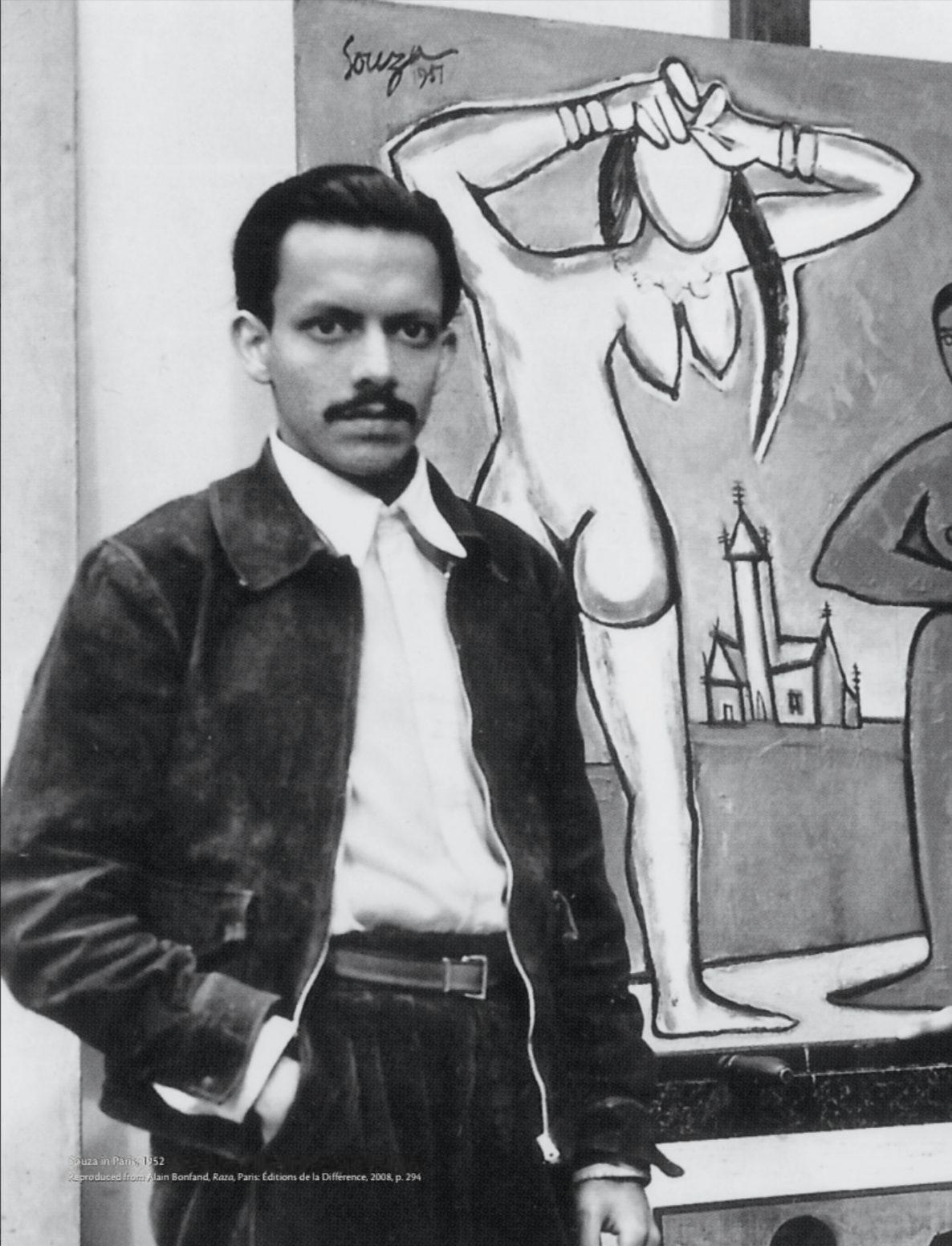

Illustration depicting Shimousa province’s soy sauce production in Dainihon Bussan Zue.

They are now following the same pattern in India – helped by the fact that Indians are no strangers to soy sauce in the first place, seeing as how Chinese food is the second most popular cuisine in the sub-continent.

Harry San works with hundreds of chef ambassadors — either professionals or self-taught who are called ‘Friends of Kikkoman’. “We first make them taste the contrast between cheaper, chemically produced sauces and ours. Then we ask them to actually cook with it. They are always amazed at the difference and the result.”

His goal is to make the distinctively reddish brown Kikkoman sauce a staple in every Indian home kitchen through personalised chef engagements or the ‘Honjozo Experience’ movement referencing the traditional manufacturing process by which soybeans, wheat, salt, and water are fermented and gradually aged over six months with the help of brewing micro-organisms such as koji mould, lactic acid bacteria, and yeast.

Kikkoman India’s marketing plan is all about finding uses for the sauce beyond pan-Asian food and becoming a flavour enhancer in a limitless range of Indian fare.

U.S. Newspaper advertisement (circa 1954).

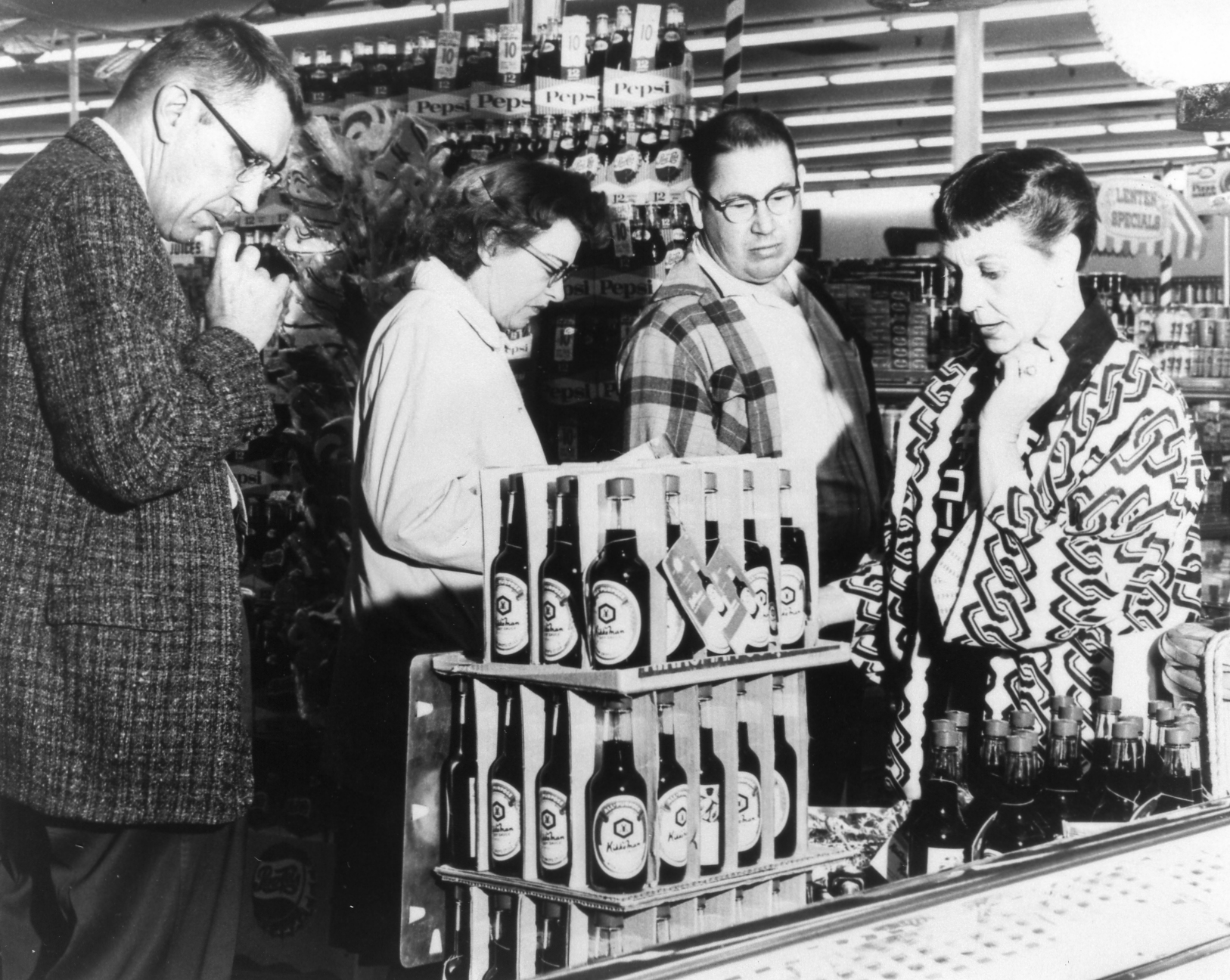

In-store demonstration at the U.S. supermarket (1964).

“Think of using it in everything from butter chicken to biryanis, samosas to desserts and even cocktails,” says Harry San, describing how he once layered a pan leaf with Kikkoman sauce and a sliver of tuna to make that perfect bite. From ancient times the soybean has been a key ingredient in the Zen-Buddhist culinary philosophy, developed by the monks and known as the Shojin Ryori principle of eating – it encourages the consumption of food that is seasonal, visually appealing, as well as balanced with light and fresh flavours. The sauce became the all-powerful taste enhancer and the ultimate game changer, thus giving it that high ranking importance.”

It’s interesting to see how an age-old family business has sustained and thrived, over the years and across the world – adapting to the times yet staying true to their values. The Kikkoman family and sauce are prototypes of success backed by heritage and family ties – a story quite relevant for our times.

Words by Jackie Pinto.

Images courtesy of the Kikkoman Group.