The becoming of history comes with loss. Stories, monuments and jewels catch dust; sometimes disappearing, to be found later. What was once an ordinary object, may see centuries of civilisation and soon, what was once the future. They don’t remain ordinary. They are rediscovered as a collectable, a sentiment, and a proclamation of one’s cultural knowledge.

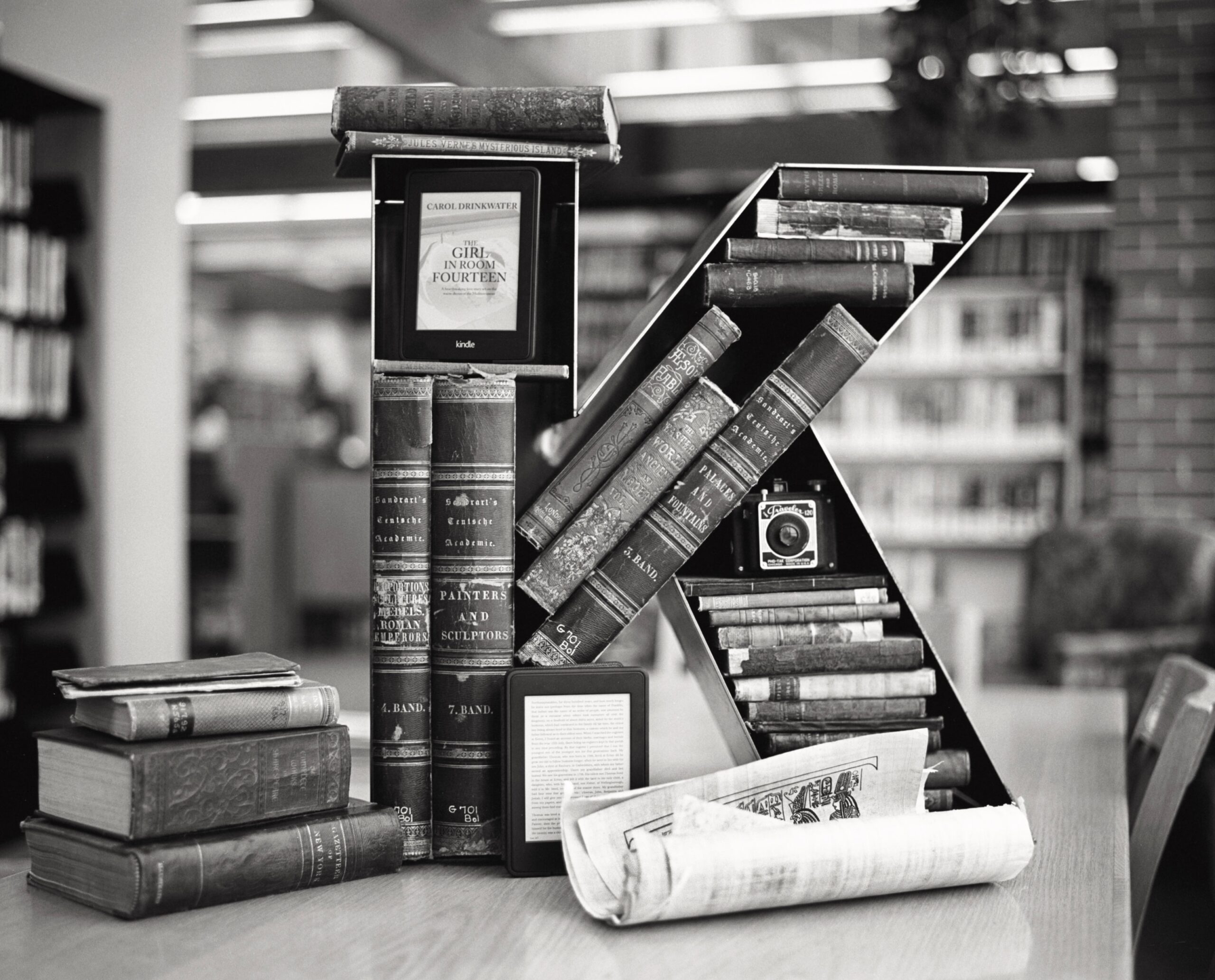

“People who are sick of buying new things, buy old things,” laughs Mahijit, the co-owner of an antique store, Krishna. Nestled cosily in the streets of Saket, New Delhi, Mahijit Singh and Nalin Tomar’s shop houses rare objects handpicked from towns across India and the world. The essence of their shop is rich with textiles not woven anymore, jewellery from centuries gone and decorative items that once adorned someone else’s home.

To quench my eagerness about their sources, he tells me about Karaikudi, a city known for its vintage and antique collections. He moves on to tell me about the Waghria family from Gujarat, who have built a vast network of reselling, meandering into the interiors of India. They go from village to village, picking antiques which then enter the chain of antique dealers. Mahijit however, tries collecting items only from the 19th century onward, for older items bring controversies. They’re found in sometimes predictable or surprising spots, finally making their way through a network of dealers, royal families, and collectors.

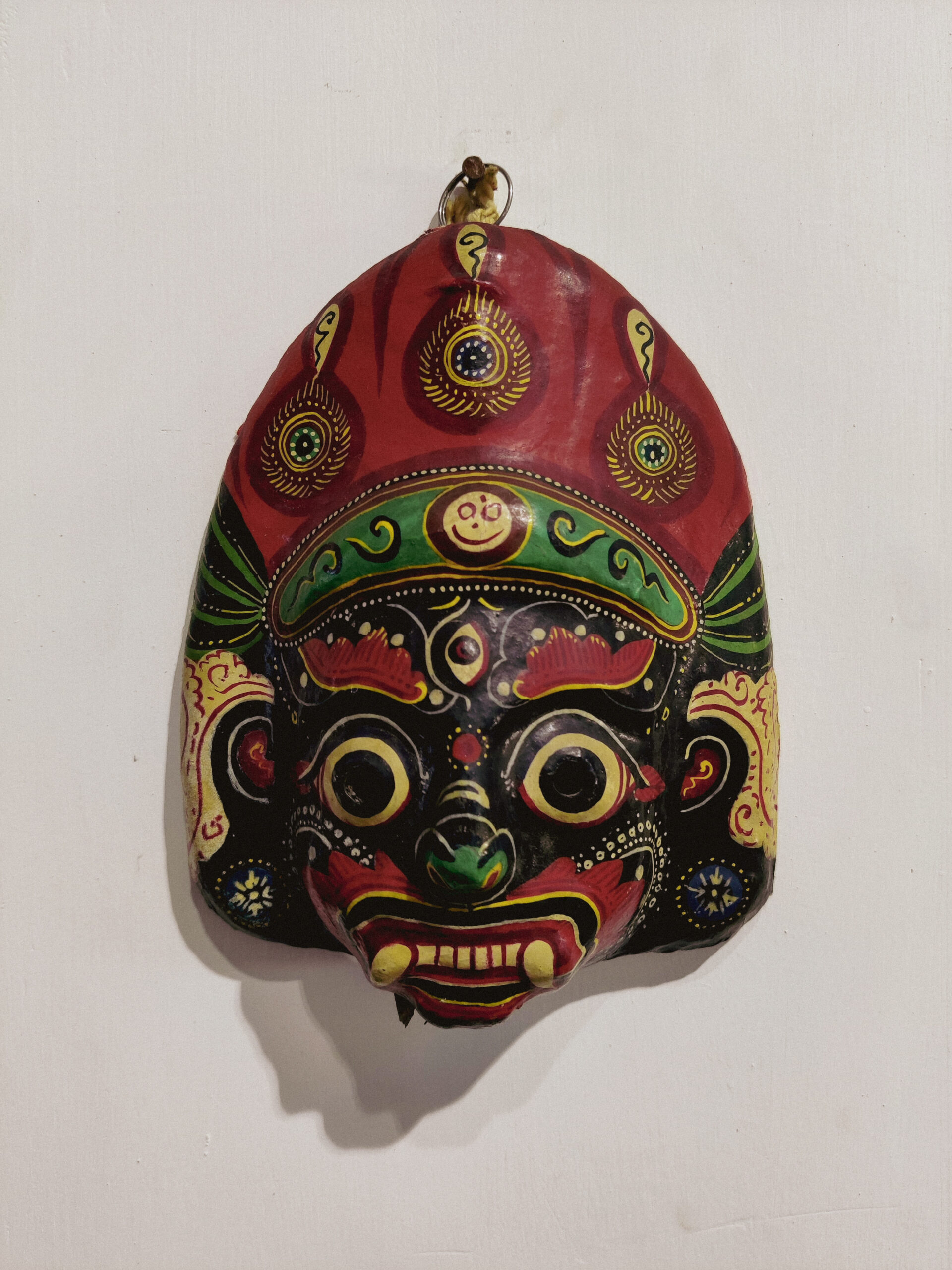

(L-R) Nooks and corner of the curation at the shop; Face mask collectible

He recalls the story of a jade dagger. After being informed by a dealer, he travelled twenty kilometres into a Jhansi village, where he saw a farmer ploughing his field. On introduction, the farmer produced a jade hilt of a dagger, which Mahijit identified to be constructed during the Mughal age. The artefact is worth lakhs of rupees today. How it came into the possession of the farmer; no one knows, but its origin stands true.

Enough peeking into the past will tell you how things are not made the same way anymore. Some carvings, finishings and artworks belong in brackets of our past; they are not replicable today. One can wonder if that is the reason they’re so revered by collectors. Is it the mere manufacturing of the object? Or is it the time warp it momentarily creates?

However, some objects come with more clarity.

Inside the Shop- looking into the Mahijit’s collection

Mahijit travelled to central India, to procure a jewellery set from a royal family. The family sold him a nath, maang tika and four bangles – encrusted in rubies and diamonds from a century ago. The nath was then bought by Mahijit’s dear friend and designer, Abu Jani, who once used it as a brooch for his sherwani.

He sourced another such piece from a jeweller in Saharanpur – a matha patti, supposedly from 1820s-Lahore, made from uncut diamonds. It belonged to a Lucknowi family that pawned it to their relatives in Saharanpur. Once free from the collateral, it reached the jeweller, who then sold it to Mahijit. “The jeweller definitely didn’t know the value of it,” he laughed. The maatha patti now belongs to the Modi family.

Mahijit’s customers understand the value of an antique, and the wealth it carries beyond monetary figures. They are in the likes of business families, designers like Abu Jani, Anju Modi, Ritu Kumar, and Paul Smith, collectors like Lekha Poddar and museums from Japan and China.

Their crevices are packed with stories from the past – some true, and some woven by our minds wandering into endless curiosities about whom the piece belonged to.

A forgotten memory is so rare to find again. Maybe that’s what we understand as valuable, as it draws us towards it, to peel its layers and call it ours.

Words by Namrata Iyer.

Image courtesy Mahijit Singh.