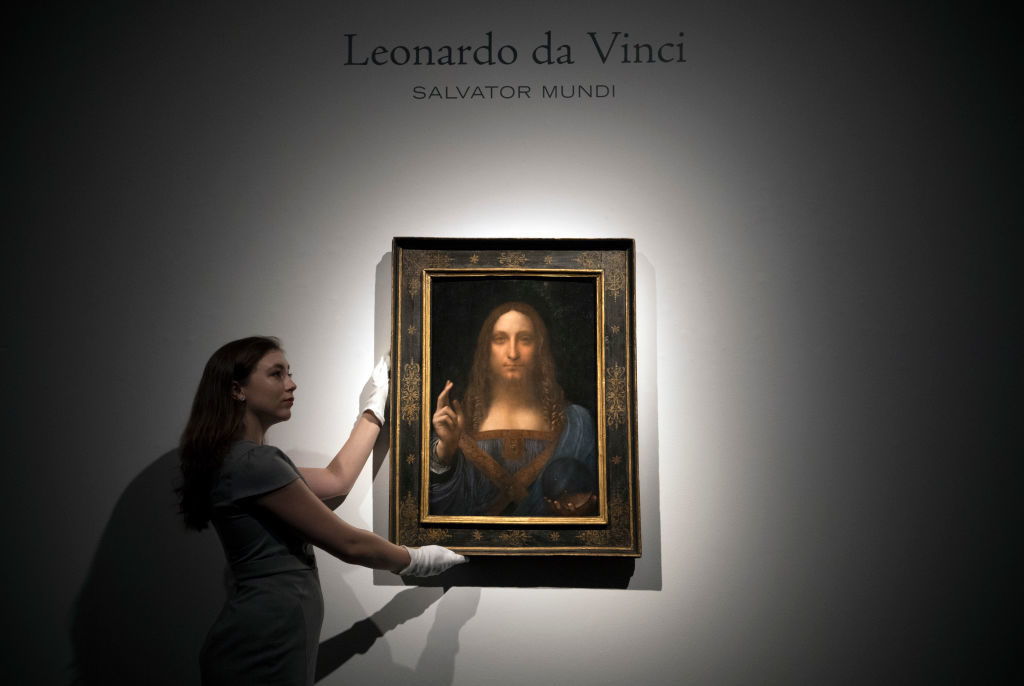

In April 2005, during the restoration process of a painting — a portrait of Christ with a modest price tag of $1,175 — Dianne Dwyer Modestini, an art historian and conservator, made a discovery that shook the art world and sent ripples into the deep sea of geopolitics, money, and power. When art dealers Alexander Parish and Robert Simon purchased the painting at an auction held at the St. Charles Gallery auction house, it was heavily overpainted and bore a resemblance to a mere copy. However, it was the consortium’s hunch, a gut feeling, and years of experience in art dealerships that led them to contact Modestini for the conservation work, just in case it turned out to be from one of the Old Masters. They found more than what they were looking for when Modestini discovered a pentimento in the painting, concluding that it was indeed from the hand of the master. It was the long-lost work by Leonardo Da Vinci, thought to be destroyed or stolen in 1603.

The artwork depicts Jesus Christ in a frontal stance adorned in Renaissance attire, clutching a crystal orb in his left hand, widely interpreted by art scholars as a representation of the world. His expression exudes divine wisdom and authority, capturing the essence of his spiritual significance. The piece is notably intricate, with meticulous attention to detail evident in the intricacies of the garments and the reflective surface of the orb. Its colour scheme predominantly features rich, earthy tones, creating a subdued yet impactful palette.

However, when the curator of the National Gallery, Luke Syson, was contacted in 2008, he enlisted the expertise of several Leonardo Da Vinci scholars and art historians to examine the painting. Notable figures such as Maria Teresa Fiorio, Martin Kemp, Jerry Saltz, and Frank Zöllner were among those consulted. None of them officially authenticated it as an original, but according to Martin Kemp, “It did possess a certain ambiguity that can be attributed to Da Vinci.” Conversely, Jerry Saltz, an art critic for The New York Times, vehemently denounced it as a malicious attempt to make money.

Dianne Dwyer Modestini

Sony Pictures released “The Lost Leonardo,” a 95-minute thrilling documentary in 2021 that chronicles the discovery and subsequent exponential sale of Salvator Mundi. The film beautifully captures the painting’s journey from restoration to its rise as a global celebrity, often referred to as ‘The Male Mona Lisa’. Directed by Andreas Koefoed, the film masterfully weaves the narrative, giving it an investigative tone that keeps the viewer absorbed until the end. Koefoed doesn’t take sides and tells the art market’s most improbable and convoluted story in an uncomplicated way, ensuring an engaging and enlightening experience for audiences.

In the documentary, Frank Zöllner, a German art historian, academic, and Leonardo expert, states: “You have the old parts of the painting which are original—these are by pupils—and the new parts of the painting, which look like Leonardo, but they are by the restorer. In some parts, it’s a masterpiece by Dianne Modestini.”

In 2011, a significant breakthrough unfolded when Syson showcased the painting in an exhibition at The National Gallery, London. The decision to present it as ‘by Leonardo Da Vinci’ rather than ‘attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci‘ stirred controversy, marking a pivotal moment. This seemingly straightforward yet impactful attribution elevated the painting’s worth to unprecedented heights.

During my visit to the Jaipur Literature Festival earlier this year in February, I had the privilege of attending Luke Syson’s session titled ‘Leonardo Da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan’, coinciding with the exhibition’s title at The National Gallery. He eloquently put forward his argument in defence of his attribution, stating that true judgement emanates from the vitality and impact of the artwork when one stands in its presence, and to him, Salvator Mundi will always be a work by the Renaissance era’s greatest artist.

(L-R) Salvator Mundi before it was auctioned at Christie’s; Auction where Salvator Mundi was sold.

Parish and Simon, the original owners of the painting, became involved with Yves Bouvier, a Swiss businessman and art dealer, in 2013. Yves Bouvier played a key role in the fate of the Salvator Mundi, also known as The Bouvier Affair. Entrusted with procuring the valuable painting for Rybolovlev, a Russian billionaire and art collector, Bouvier employed unconventional tactics, including enlisting a professional poker player to negotiate the price with Sotheby’s.

Despite agreeing on a sum of $83 million, Bouvier misled Rybolovlev, stating the price as $127.5 million. As Rybolovlev delved deeper into the transaction, he unearthed a series of similar deceptions, prompting him to take legal action against Bouvier. “I have lost everything since that incident,” says Bouvier in “The Lost Leonardo.”

The Bouvier Affair proves that luxurious art has developed into a tool for covert wealth management that enables people to move enormous riches outside of conventional banking institutions. Paintings like Salvator Mundi are used as players in a high-stakes game of financial scheming in this enigmatic dance of grandeur and secrets.

The Mona Lisa displayed at the Louvre

Fast forward to 2017, and Rybolovlev enlisted Christie’s to auction off his art collection, including Salvator Mundi. The promotional video even featured Leonardo DiCaprio. The painting shattered all records, fetching a staggering $400 million, with an additional $50 million commission to Christie’s. Rumours about the mysterious buyer proliferated, with speculation suggesting that Mohammad Bin Salman, the Crown Prince and Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia, had kept it on his yacht.

In the fabric of art history, Salvator Mundi emerged as an enigma, a painting whose journey from ruins to global renown mirrors the complexities of the human experience. From a modest restoration project to its record-breaking sale at auction, Salvator Mundi has transcended mere canvas and pigment to become a symbol of intrigue, controversy, and fascination. And yet, amidst the speculation, one question looms large: nobody knows where the painting is today, adding yet another layer of intrigue to its already enigmatic tale.

Words by Raj Ajay Pandya.

Very good

Very good Raj