How do you express yourself when your identity is already visible?

It’s a question I pose to three creatives across disciplines, with their faith, Sikhi, as the common denominator: Gurdev Singh, a visual artist rooted in his culture and ways to challenge it; Gurjeet Singh, an artist toying with yet profoundly working with soft sculptures, and Sukh Sohal, a creative director and designer carving the middle ground of identity via fashion.

The men sit, speak, and think with stark contrasts — their beliefs, while not too far from each other, are expressed uniquely. I deduce that Gurdev revels in the playground of ‘plenty’ and a willingness to return to a certain Sikh fluidity, one that Gurjeet perhaps already revels in “by the grace of his family.” Sukh’s creative leaning isn’t all that distant, but the clear understanding of fashion and faith as separate entities makes for an expression that’s easy to point out. But it’s the complexity of these creative expressions through fashion that I remain interested in — is faith a driving factor, or part of the result?

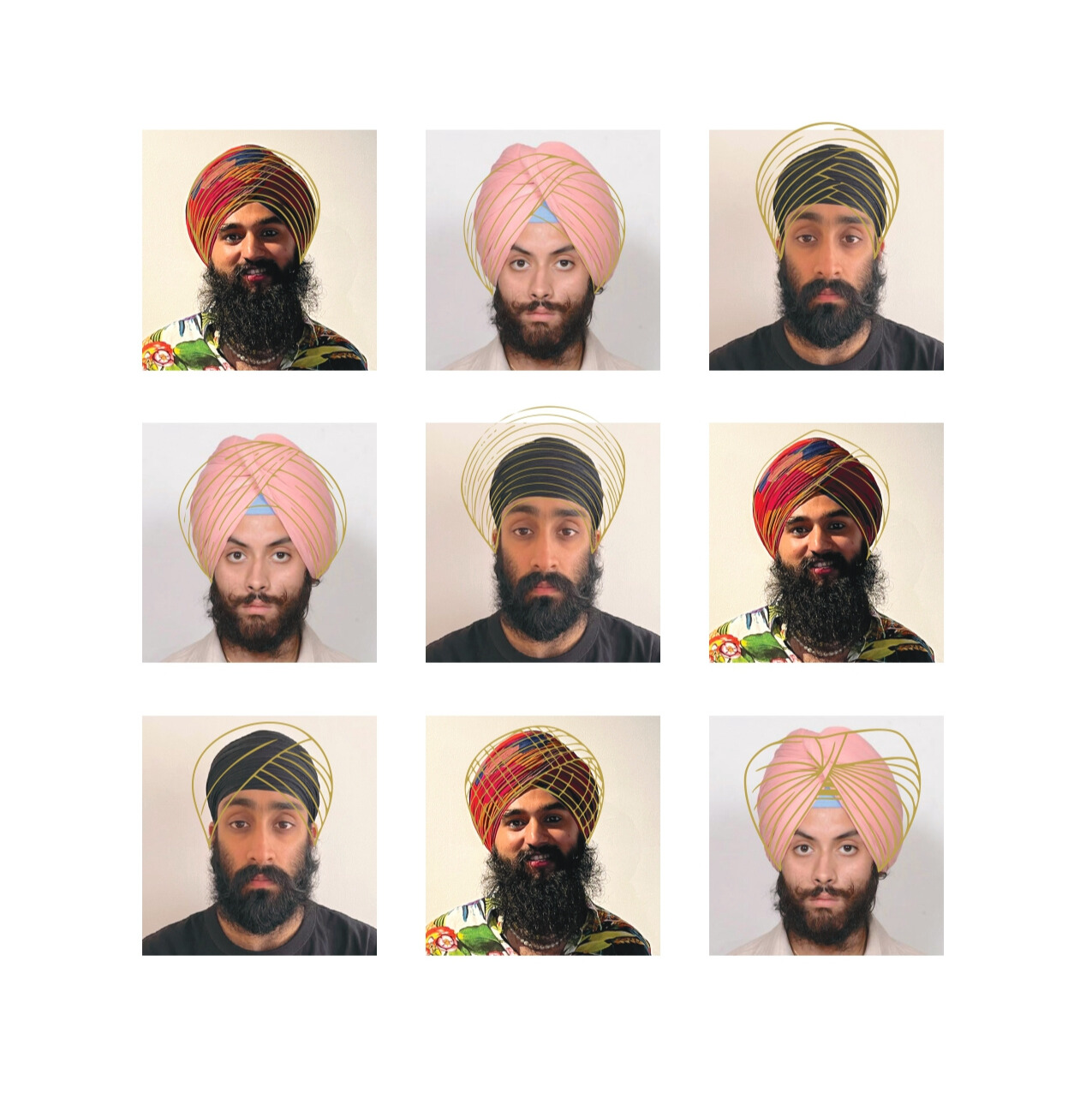

Various versions of the Sikhi faith peak through the creatives’ work, play, and fashion

Faith and fashion have a longstanding relationship, albeit varied across the world. What we wear has not just covered the body — it has proclaimed belief, signified belonging, and expressed spiritual discipline. The Christian clergy has its cassocks and stoles, the Buddhist monks don their ochre robes, while the hijab and abaya signify Islamic faith. In modern day, however, faith often supersedes these guided notions — there’s a certain freedom and a will to wring it, while figuring out what one’s individuality truly is.

So what is theirs?

On faith and its weight, things are a bit open-to-interpretation with Gurdev. He’s here to have fun — and he’ll make sure you know it. “I want my work to be absurd — it may have meaning, it may not have any. As an artist, I think you should be ready to change yourself at any moment. You never know what the audience will like, and when.” We talk about how the clothed expression of Sikhi of today — in its more muted tones and straight silhouettes — is not what he aims to follow. Sat amongst the various colours of the many belongings that occupy his room, he readily shares his screen — images of the Maharajas of Patiala, an erstwhile princely state, show up. These men from a time gone by, dressed in softer silhouettes, sporting the most elegant jewellery are part of his inspiration. “Hypermasculinity is anti-art,” he says. The inherent need to be “more Sikh” is absent: “Sikhs used to be flamboyant. Look at the pictures of Maharajas — they had piercings, earrings, jewellery. My inspiration for fashion is this.” He then points me to the 1964 Partisan Review essay Notes on Camp by American critic Susan Sontag. She considered Camp “a sensibility that, among other things, converts the serious into the frivolous.” Much later in our conversation, I ask Gurdev whether fashion carries spiritual weight — he nearly chuckles as he leans back in his chair and says, “I don’t know. This is just fun.” Days later, while reading Sontag’s notes, I found what I believe represents Gurdev well: “Camp taste turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgment. Camp doesn’t propose that it is in bad taste to be serious; it merely asserts that nothing in the universe is to be taken quite seriously.”

(L-R) Gurdev’s ‘Middle Class Maharaja’ — a persona marrying a certain royalty with everyday life; The visual artist sporting one of his simpler yet bold looks. Photographed by Ashish Negi.

A back and forth between fashion and faith seems inevitable, but it’s what forms the breeding ground of ideas and expressions, particularly for Sukh: “Earlier, [fashion and faith] were separate. In university, I began adding layers — this is who I am, this is what I wear everyday, so why don’t I express myself how I want to express myself? The sardars around me didn’t view the two as separate worlds entirely, but it’s what they were used to,” he says. He took time too, to realise what makes Sukh, Sukh — identities aren’t borrowed the way cultural traditions are, and often require a bit more work. For a UK-born and raised sardar, things are a bit more complex. I ask him if the understanding of the various cultures in the UK — influenced heavily by Black culture — was a gateway to understanding his own Sikhi better. He’s prompt to respond in the affirmative. “Indians and South Asians haven’t been rebellious or been that confident. We’ve always had an inferiority complex given that colonialism is so deep within our country. We’re always having that constant battle of trying to etch out of it. So having those cultures and communities trying to really represent themselves is a beautiful act that actually gives us the confidence to do so much more as well.”

Elsewhere, dressed in a deep red Gul Sohrab shirt, Gurjeet sweetly circles his answers to each of my curiosities back to his family. Sikh culture is nearly synonymous with his family’s values and the lessons they share — experienced in the excitement they hold for his work, and the enthusiasm for his fashion. In his hometown 50 kilometres away from Amritsar, bordering Lahore, people are conservative. “My family is very emotional — if they don’t understand something, they try to understand the emotion behind it.” And so, with the strength he gained amongst loved ones, he learnt that he “doesn’t want to be controlled.” “I realised when I began putting myself first, I lived a happier life,” he says. Loud colours, prints that make you look twice, and uncommon combinations seem to bring a smile to his face. He tells me, “In fact, my tailor tells me he enjoys stitching my clothes because they’re so different, and others ask about them too — I think he may even have hiked his prices!” And while he acknowledges certain shortcomings in his culture, his Sikh faith has made him what he is. His fashion is a result of the confidence he gains from the goodness in his community, and a belief that even the traditionalists simply need more information and exposure. “My faith is my comfort, and so is my fashion,” he puts it simply.

Playful colours and patterns find each other in Gurjeet’s presence. Photographed by Harsh Jimnani.

The three men and their artistic expressions see no overlap. But the interpretation of their faith sees commonalities in their view of the world, and how they place themselves in it. To each, faith is personal as is their fashion — but both are a form of expression that is unlikely to be recreated. While Sukh, and his fashion brand lohaS (his last name inverted) navigate an amalgamation of his 30 years in the UK as well as his roots, Gurdev aims to move what he calls the “cultural needle” to normalise critique of cultures, and Gurjeet grabs on to each new opportunity to learn something new from Sikhi. Not each step of their journey is an entanglement of faith and expression, but it’s several things at once — long-standing inspiration, a continuous tussle, and a thought-provoking identification of ideals.

Sukh within a familiar setting of lahoS’s workshops. Photographed by Ashish Negi.

As I speak to each of them, I attempt to find a common theme that underlines it all — what is their relationship with faith and fashion? What allows them to create from faith, or create for fashion? Do they even spend time thinking about the two concepts together? Sukh’s articulation backs up the form, design, and silhouettes of lahoS — he knows where he comes from, and understands that his creative expression is a unique reflection of him, his faith, and his culture. Gurdev’s nonchalance yet pointed references of his culture’s past and present make me understand his art better — sometimes ridiculously intriguing, other times, a collection of what I imagine to be artful quips. In his heartwarming presence, Gurjeet emphasises the importance of expression — his, via fashion and art.

I’m still wondering whether belief is only ever led by faith, or whether there’s room for it to be led by creative expressions like fashion. And to leave me thinking, but also giving me a self-sufficient answer, Sukh says, “Faith gives you hope, and hope gives you creative expression.”

Parts of the interviews have been translated from Hindi to English for the purposes of the story.

Words by Meghna Mathew.

Featured image by Harsh Jimnani.