A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know- Diane Arbus (American Photographer)

Titled ‘What the Camera Didn’t See’ an exhibition by Alexander Gorlizki and Riyaz Uddinat MAP, literally blurs the boundaries between photography and painting by transforming stiff, stoic subjects in vintage photographs into surreal fantasy paintings using a 600 years old Indian art tradition.

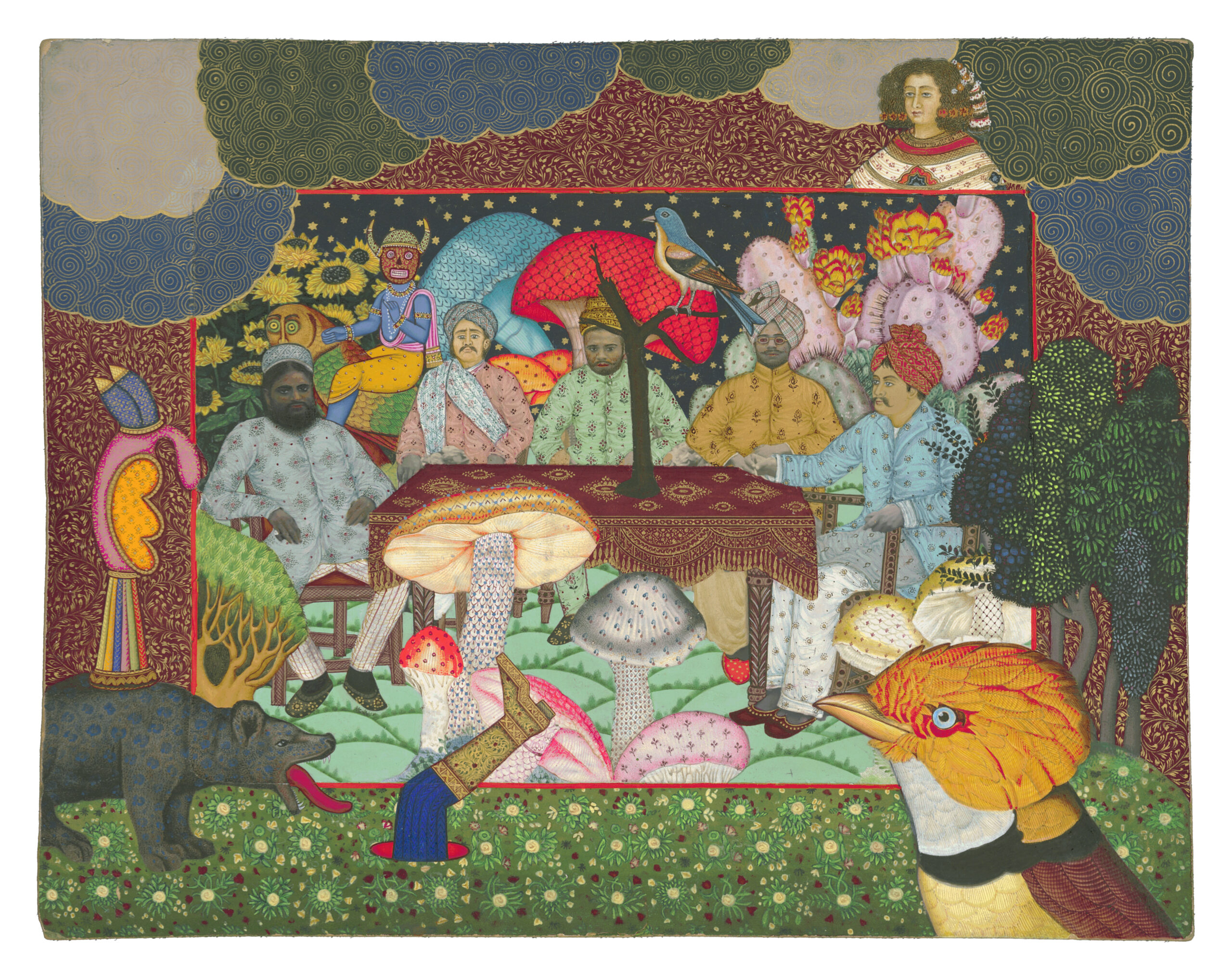

(L-R) New Posting, I didn’t mean it

2023, USA-India

Pigment and gold on paper

Various sizes

British born Alexander Gorlizki first visited India in 1983.

“A family friend and Indian sculpture scholar took me to Sanchi. I was fascinated by the ancient sculptures of the Naginis, set among the rolling hills and unique landscape, and that feeling of wonderment has stayed with me ever since,” he begins.

Gorlizki currently lives and works in New York, but his connection with India, forged during that very first visit, runs deep and wide. In the mid 90’s he established a studio in Jaipur, along with Riyaz Uddin, a master painter specialising in miniature art, an ancient art form going back over 600 years. They have been close friends and associates for the past 26 years.

Gorlizki creates wonderful, fantasy drawings, Uddin breathes colour into them with jewel toned pigments, stone colours and gold leaf, using just a single haired brush.

The result is mesmerising.

Currently exhibiting at The Museum Of Art and Photography, the exhibit is a series of 23 works, ‘created in response to a set of photographs in the MAP collection and on actual vintage photographs’.

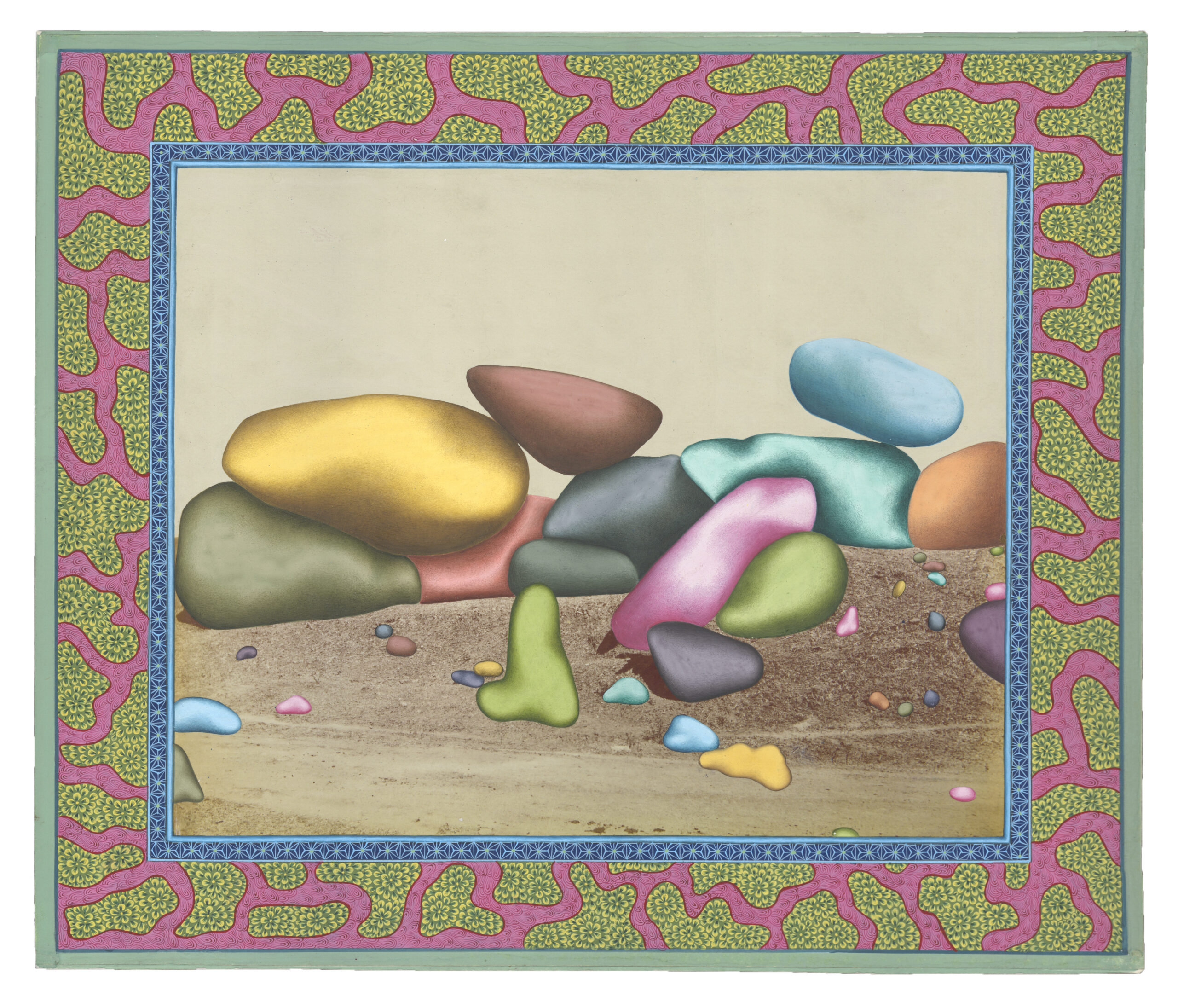

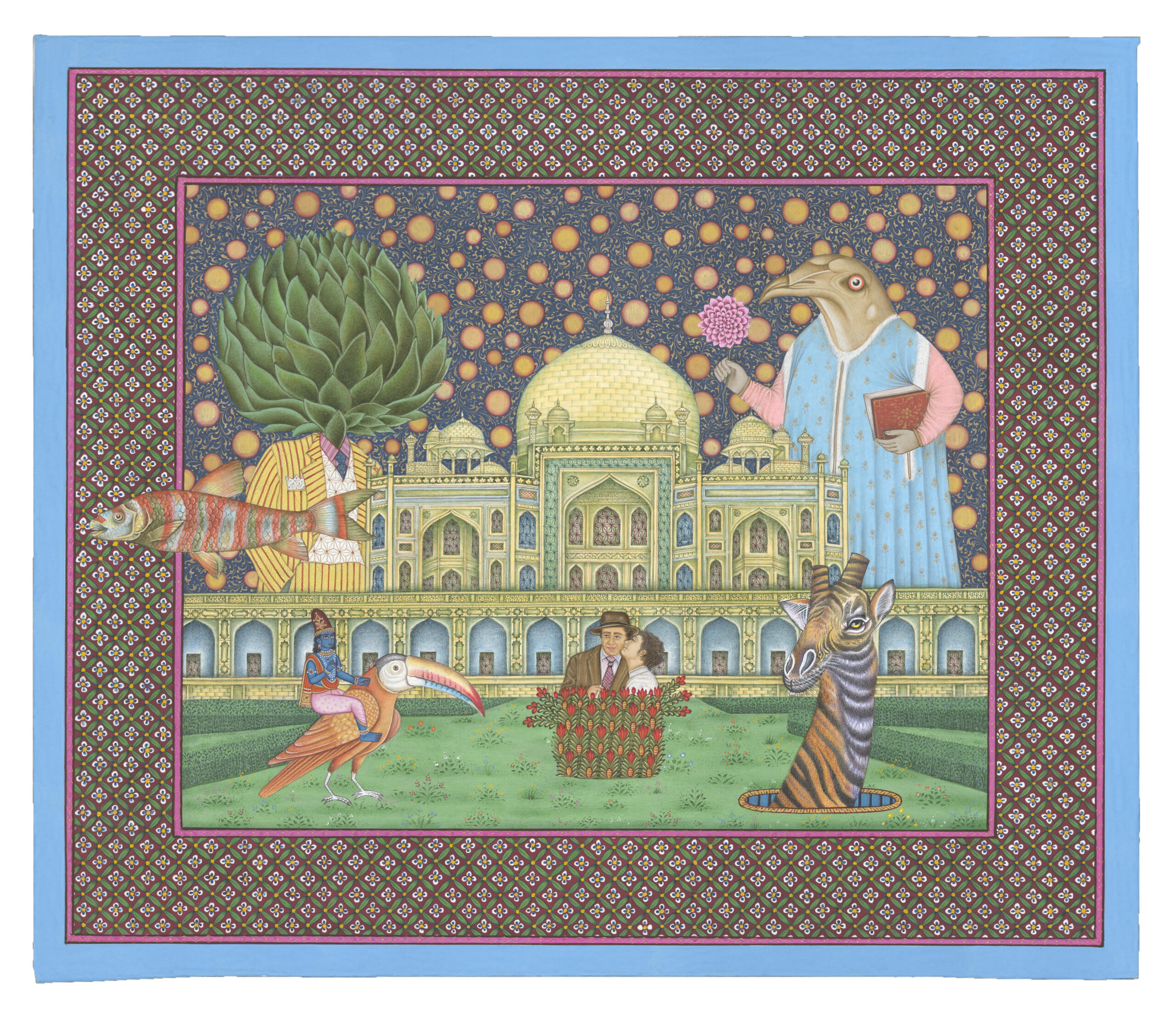

The paintings are surreal, fantastical, playful dreamscapes, encouraging us to combine the surreal and the mundane and reimagine our everyday relationship to spaces and objects. Inside each finely detailed frame is the happy co-existence of different histories, cultures and visual languages happily merging and re-contextualising.

Street Scene

2023, USA-India

Pigment on digital photograph

Image: H. 21.2 cm, W. 25.4 cm

Stoic, ordinary faces morph into royal visages, pipe smoking fish drift past a group of mustachioed aristocrats, colourful magic mushrooms seemingly rise out of the earth and surround a turbaned prince. Each work is richly detailed in the grand tradition of miniature art, yet so different in the narrative.

Apparently Gorlizki’s fascination for Indian art goes back to his childhood years spent in his mother’s antique shop where she dealt with textiles from Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Central Asia, then under Soviet rule, as well as stuff from North-West Pakistan and India.

“I guess my exposure to Asian art was organic in that sense. I was probably drawn to Indian Miniatures and their intricate detailing as a child, although what I saw might have been reproductions. However, what has sustained my interest over the years is my collaboration with Riyaz, and through him getting involved in the form itself, artistically.”

Gorlizki’s 26 year old association with Uddin has brought to fruition a unique, mystical take on the dreamlike realm of Indian miniatures. “I spend a lot of time studying historical Indian miniature paintings. I find that they all have certain features in common even if the styles, themes and subjects differ. For example, the intricacy of the brushwork, the way the figures are staged in relation to one another, often in profile, the judicious use of borders, arches and windows that seem to indicate a portal or gateway to another world. People often assume that miniature painting alludes to the small scale of the artwork whereas it actually refers to the fine detail of the brushwork. Because of the time involved in the minute detailing, paintings are generally smaller but the same technique can be applied to three-dimensional objects and a wide range of subjects. Because I work with Riyaz , one of the most talented living miniature painters, as well as with a group of his assistants, I’m able to explore new ways of applying and combining these techniques. Before we are happy with the final work, they are passed back and forth between the studios in Jaipur and Brooklyn so they really evolve over extended periods of time,” explains Gorlizki, adding, “I also enjoy working with indigenous craftspeople, like, carpenters, embroiderers, sand casters, marble carvers, spectacle makers, cobblers, knitters, tailors, watchmakers, stone masons, manicurists among others. I have also worked with professionals in different fields like forgers, fakers, designers, musicians and film-makers. By working with them and observing them closely, the subject matter of my material evolves. It’s all about finding magic in the mundane. I admit I am also inspired by Edward Lear who was a famous 19th-century writer, popular for his clever limericks. He was also a very talented natural history illustrator. His colourful birds like African parrots and parakeets were outstandingly beautiful. I’ve borrowed from his vibrant colour palettes to use on European style paintings of elephants adding tiger, leopard, zebra patterns to come up with my own weird creations,” he smiles.

(L-R) Skyfalls, I didn’t mean it

2023, USA- India

Pigment and gold on paper

Various sizes

The two artists have a simple collaborative process. Once Gorlizki has formalized his visual imagery, iconography, patterns, colours, language and imagery in his mind’s eye and transcribed the same on the material he is using, he sends the works to India, where they are meticulously hand-painted in Jaipur by Riyaz and his studio team. It goes back and forth until they are both satisfied with the result.

‘What the Camera Didn’t See,’ compels you to join the artists on a mystical journey. Leave the mundane behind. Quite literally embrace the past, and swap formal images in sepia toned pictures for vibrant fantasies and playful sceneries where highly finessed art techniques are used to create visual alchemy.

Words by Jackie Pinto.

Image courtesy Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru.