For the first time in a long time in 2021, guests and press personnel were called to 10 Avenue Georges V in the heart of Paris to experience a reenactment of history. Contextualising history in a modern context, Demna Gvasalia (creative director of Balenciaga) presented the first Balenciaga haute couture show in a long time, to be precise – 53 years since Cristobal Balenciaga closed the his eponymous couture house. For a visionary like Demna, this re-imagination was not just an homage to the greats in fashion, but also a strong and poignant re-contextualisation of his history and the story of his people. A Georgian who had to escape his country in the face of war, artists like Demna classically never “belonged” to the fashion Industry, let alone the haute couture world of fashion – the private club within the private club.

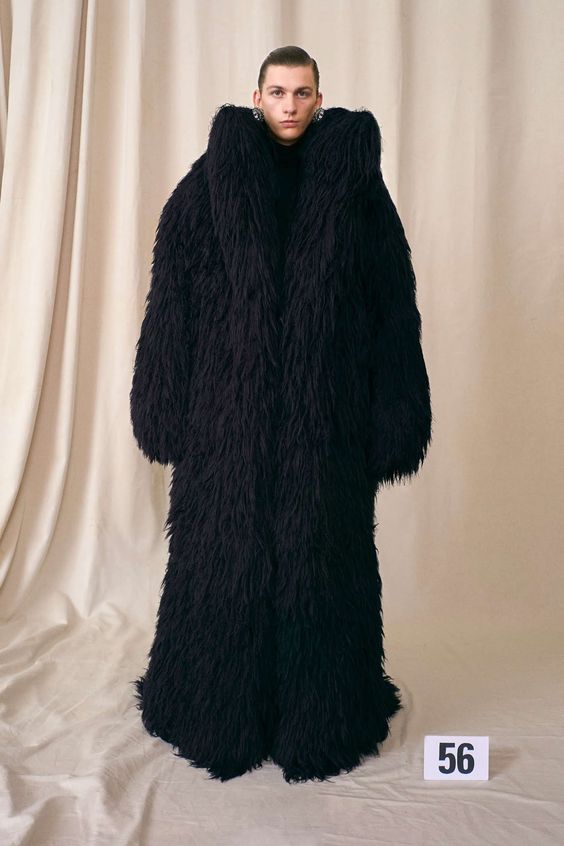

Balenciaga Haute Couture Fall 2021 collection

To delve further into this, it’s imperative to understand why haute couture is revered in the fashion world. Translating to “high sewing” in French, the word refers to the creation of exclusive custom-fitted high-end fashion design that is constructed by hand from start-to-finish. Many confuse with plain old high-end fashion, but there are hand-made and bespoke intricacies that make haute couture stand out from regular high fashion.

While the show in a way reignited the lust for haute couture and brought it back to life with its sheer precision and performance, it also shone upon the under belly of the fashion world. With designers like Demna, his brother Guram Gvasalia now at Vetements (a luxury fashion house founded by Demna), the late great Virgil Abloh (artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s menswear collection), Yoon Ahn (creative director of Dior Homme’s jewellery) paying homage to the artistry of their business’ forefathers and foremothers, the complexities of the haute couture world are revealed. Questions are raised on the inclusion of indigenous culture; and out of the many questions it presents, I ask you this – what makes a Cristobal Balenciaga, Christian Dior, Demna Gvasalia, Virgil Abloh different from your local indigenous tailor or masterji?

In a previous article, we delved deep into the history of tailoring in India and how engrained the process of tailoring is to the very essence of Indian living. In examining this lost art, I came to realise that I did not see much difference between someone like Cristobal Balenciaga or my local masterji in Connaught Place. In both these scenarios, clients go to specific maisons that make pieces meant to be tailored to perfection. After all, Balenciaga and further on Dior and Chanel were known for their cuts, lines and the silhouette of their clothes. Even later on, designers like Martin Margiela, Rae Kawakubo, Alexander McQueen, Yves Saint Laurent, Karl Lagerfield, Kim Jones, etc. became synonymous with high fashion because of their cuts and their haute couture approach to ready to wear fashion. Upon investigating the same, it appears that even independent, unknown designers in the Western part of the world are considered haute couture, even though they aren’t specifically big established brands.

So what really, is the difference between tailoring in the Western world compared to the Eastern World? Why is a piece of tailoring made in some Rue in Paris haute couture, but something made in the streets of Benaras or Delhi not? Why are independent fashion companies maisons but a tailoring shop in Kanpur that has been run by a family for generations not one? Aside from the very visible distinction based on race and colour, it seems like the concept of haute couture is something that is associated directly with the amount of money a tailor made dress or a suit costs. A $4,000 Schiaparreli gown is haute couture, but a carefully crafted $60 wedding saree made in Benaras isn’t. Both pieces are highly intricate, use high quality materials and skills that take years and generations to perfect, and most importantly are custom-made. If we were to even look at the official requirements of a haute couture show for Fashion Weeks around the world, most, if not all tailoring shops in India would easily make the cut. What is further interesting is that even though many different regions in India are known for their own textile-based specialisations and a rich history of using varied kinds of fabrics and techniques, they are more so presented in a very touristy way – as if it’s something you observe from a distance and commend it for its art.

The same hasn’t reached to the level of people actually wanting to wear these garments. At the same time, localities and areas around India are also domestically known for their tailoring prowess and what they can provide at affordable rates, be it Jainsons Emporio in New Delhi or more conglomerate-based businesses like Fabindia and Anokhi that offer ready to wear alternatives for traditional Indian tailored clothes. Sadly, these aren’t the same as haute couture as it’s more of ready-to-wear fashion.

Beyond the simple scale of economics and the inherent white and western gatekeeping in the fashion industry, it seems like the Indian consumer itself sees this divide and reinforces it. The reason why most wedding tailors are now struggling with their business and are lusting for that Sabyasachi lehenga seems to be this same economic divide. Because one is expensive, marketed and presented in a mainstream manner – it is something that showcases ‘class’ or ‘status’. It is the same reason rich oligarch wives go to Balenciaga, Dior and Chanel.

It also becomes apparent when Sabyasachi collaborates with H&M and puts out essentially a pattern shirt for an increased price, or when Gucci puts out a $900 Turban. Although one can argue that the rise of brands like Sabyasachi and other designers such as Gaurav Gupta, Siddartha Tytler and older staple houses such as Manish Malhotra or Tarun Tahiliani have brought the limelight to Indian clothing culture and techniques, the current ‘haute couture’ world of Indian fashion seems to very much be taking directly from its domestic roots without helping the tailors or masterjis that have spent years perfecting their craft. Traditional Indian tailoring in the ‘haute couture’ field seems to live only in the exclusive clubs of tier 1 cities in India, forsaking the history and heritage that inherently is the reason for its existence.

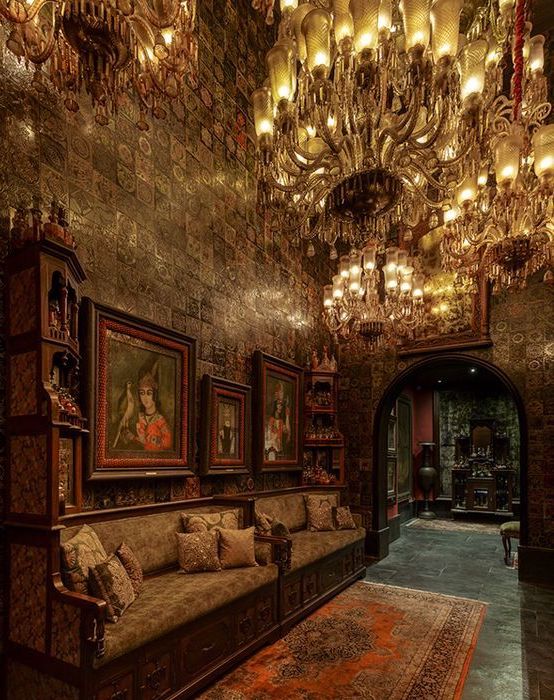

L-R Sabyasachi Flagship Store, Torani Flagship Store and Gaurav Gupta Flagship Store

With the surge in people of colour and designers from across the world breaking the moulds of fashion, it is probably high time we reimagine and relook into the definitions that are dictated to the industry by big brands, conglomerates like LVMH and WGSN and even how we look at tailoring in India. If we were to actually apply the same standards to the tailoring in India, India could be and probably would be the couture capital of the world.