Ravish Kumar and Vinay Shukla have been fielding questions with equal parts good humour and earnestness since the release of the documentary feature film While We Watched in 2022. A few minutes into our conversation, and their natural affinity is evident. Ravish’s career in television journalism spans three decades of meticulously curated ground reports, critical commentary and investigative stories. He focuses on what gets swept under the rug of political and corporate greed. Vinay has made the ‘insignificant man’ his object of interest and it is not difficult to see what drew him to Ravish. With accolades like the prestigious Peabody Award (2024), and awards at Los Angeles Indian Film Festival (2017), Doc NYC (2023) Helsinki Documentary Film Festival (2023), Busan International Film Festival (2023), to name a few, Vinay has delicately placed his finger on the pulse of Indian political drama.

It is relatively early in the morning, however, Ravish tells us that by now he wraps up working on his video content. Time is precious so we begin right away. I ask him about his relationship with language(s), particularly Bhojpuri, Hindi and English, and how he navigates their relational power dynamics in his profession.

“This is a very interesting question. Primarily, I am a Hindi journalist but since my earliest days and even today, I feel this pressure of English, all languages of the world do. But I have never adversely judged the world of those who speak English. They have played an important part in my life. Today, I hesitate while going abroad because I feel a language barrier. I speak and am expected to speak more while I have not even managed to say what I wanted to in the first place. I use up my limited vocabulary like a data pack or a sachet of shampoo and am left with nothing.” We laugh. It could be the conversationalist in him or the wisdom which knows certain topics cut deep and must be offered with a side of laughter.

“I ask for help, have some thoughts put together by friends who speak English, but it is not the same. It is like sitting in Ambani’s drawing room, what should I look at? The vase or the 4 crore watch?” he says with his trademark dry humour and wry smile. “But the awkwardness is subsiding. I have to credit the university professors I met abroad. They are more receptive. They have shed the arrogance of English. They are curious, they are cordial, and it makes me wish I knew the language better and could have more meaningful conversations with them.”

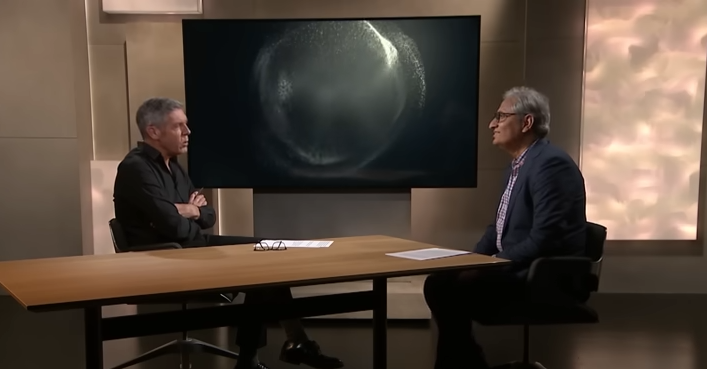

Ravish Kumar in an interview with The Listening Post — hosted on Al Jazeera English.

Over the years, Ravish has protested against the vulgarisation of the Bhojpuri language in its cinema and songs. His relationship with Bhojpuri is more sentimental than that with Hindi or English. “When we used to speak Bhojpuri, Hindi seemed like English does today. It has a conflicting relationship with Bhojpuri and offers more scope, opportunities. I look for people I can talk to in Bhojpuri. My late mother spoke the language. When someone asks me what my mother tongue is, I say it is Bhojpuri. My Hindi teacher used to say, ‘Speak whichever language you want but respect it’.” Ravish has a lot to say about language. But listening to everything he says points to his root principle which is anchored in ‘goodness’. For him, a language is good not when it is “eloquent”, not when it requires a “dictionary” to be understood, but when it contains “diversity of voices.” “For language to appeal to the listener, it has to come from someone with integrity and honesty since dishonesty in life seeps into dishonesty in language”. No matter the subject under discussion, Ravish, like a compass, directs us back to the values of moral steadfastness.

On the perception of languages within his industry, Vinay says, “When I started telling people that I was making a film on Ravish, my English-obsessed friends went ‘Why not Sreenivasan Jain, Barkha Dutt or even Nidhi Razdan? Why him?’ — ‘Why not? You see them, know of them, you do not want to know of anyone else.’ It gives you an insight into how much the English love English. I wanted to push against this idea and it is one of the reasons we made the film.” This is surprising to me, because growing up, to us, NDTV meant Namskaar, maen Ravish Kumar. “I hope that it serves as a bridge between different audiences.”

Namskaar, maen Ravish Kumar — salutation by the veteran immortalised through his prime time show in the mainstream media.

Vinay uses his own language in the documentary — that of silence. I ask him about the balance he has maintained between dialogue and silence. “Filmmaking is my second job, introspection is first. Whatever time I could find in the film to create moments of introspection, I did. While watching a movie, my heart wanders and I sometimes use music, dialogue and silence to convey that. These are just steps in a ladder to reach that heart, there is no definite road map.” Both Ravish and Vinay have a way of centreing the ‘heart’ in all discourse. It reminds one of the qalb (heart) as a thinking, spiritual core in Sufism. Vinay says that the struggles of choosing what stays in the film and what is edited out is only the surface of his true intent; that of engaging the audience in mutual introspection. He calls this documentary a “Shakespearian drama” which rings true since Ravish remains in the throes of a Hamletian dilemma of ‘to continue or not to continue’ as the tension escalates. The camera is silent, Vinay is silent, Ravish’s silence is louder than words. Perhaps it is a filmmaker like Vinay who can bring out such poignant silences from his subject.

Another technique which Vinay uses throughout the length of the film is that of tension. I ask him about tension, hope and relief. “At the end of the film, I did not want a major redemption. I did not want a Lagaan-like moment where the entire village is dancing in the rain. ‘We Won! The End!’ It has been two years since the release of this documentary, and before that it was in editing. It released in a society different from the one in which it was filmed. I wanted to stay true to the feelings in that moment. That is where the tension comes from. It was reflective of how I was feeling.” Does he think that today, especially after the election results, the hope his documentary offered has been answered, even to the smallest degree?

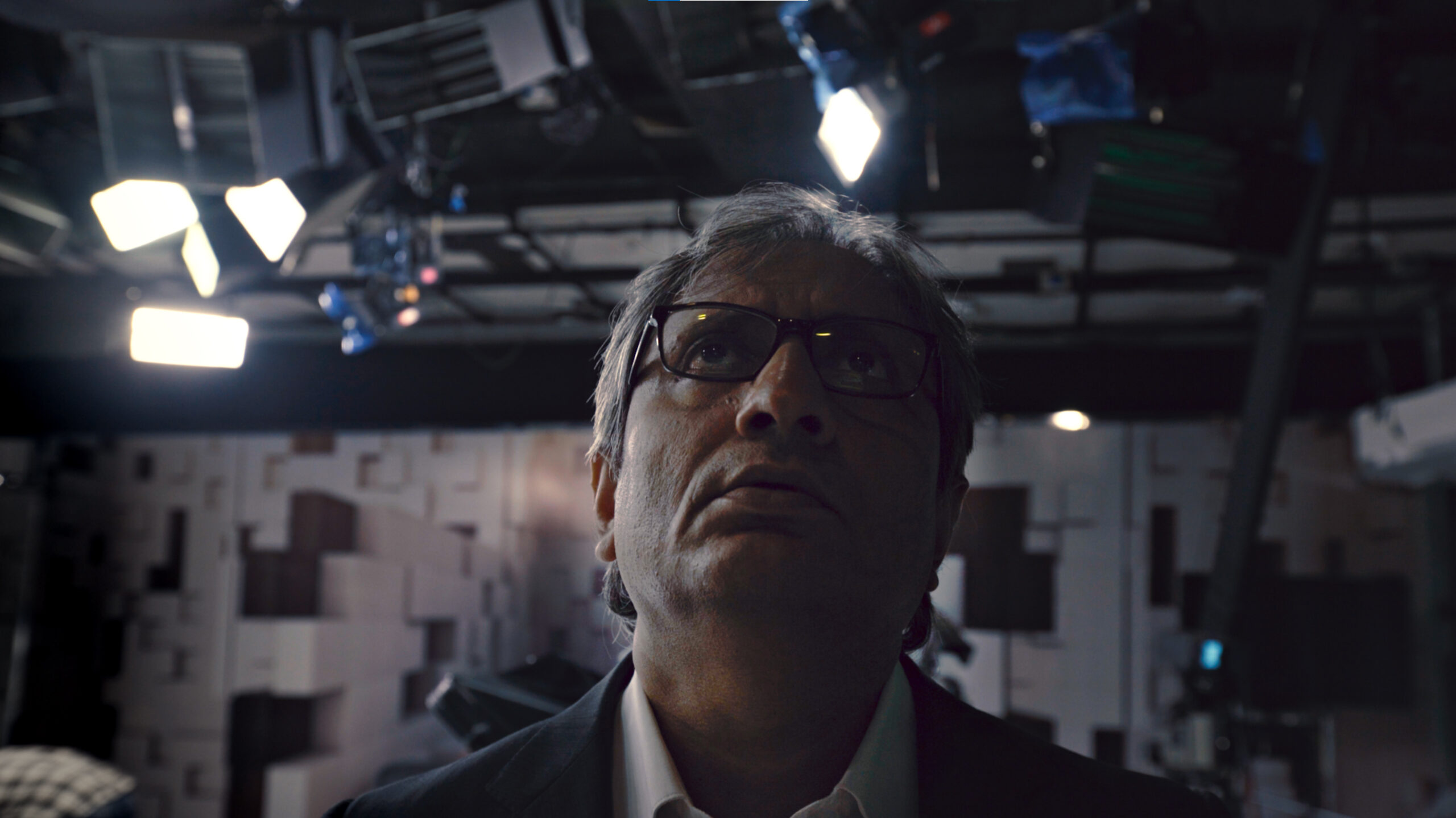

Moments of introspection. Still from the movie — While We Watched.

“I try and stay away from getting too hyped or pumped about election results. To say the film contributed to the result poses a challenge. Because if the results had not been what they are, we would have to say the film failed in its purpose. Electoral verdicts are ever-changing. The film is about key conversations, so connections are made. But there are many contexts around a film; it is amorphous and hard to pinpoint which factors elicited certain responses. I am grateful that people responded the way they did and some have kept the film within them.” With his hand over his heart, he says, “We have not stopped talking about the film, answering questions because newer people are discovering it every day. They talk with a lot of love about it. They reach out to Ravish with heartfelt messages. That is enough for me.”

Ravish is known to have used elements of the theatrical in his Prime Time episodes. He says it is in his nature to “experiment”. One episode sticks out, where he used a dark screen with text rolling for 30 minutes, as he delivered his monologue. It was an episode on political prisoners, particularly Umar Khalid. He remembers it well. “But I have lost a lot of viewers now.” After NDTV, his initial days with the YouTube channel were “frustrating”. “(At NDTV) people used to call me all night after an episode, then came a time when there were no calls or messages.” With bemusement, he recalls the only two viewers, one from Lucknow and one Delhi, who would message him with feedback and appreciation for his videos. It is heartening to see how this experience was not a curtain call on his career but a new “challenge” wherein he learned all over again how to interact with people, engage and build a viewership. “I was clear about the path I wanted to take, it was an individual decision, no one could have taken it for me. Whether on television or YouTube, my principles regarding this work remain the same.” He fondly closes the chapter on his studio days, using a phrase which hangs heavy, “Ab voh bohot duur ka ateet hai.”

It evokes moments of bereavement in the film, where cakes upon cakes were brought into the studio to bid farewell to Ravish’s colleagues; layoffs due to budget cuts and people quitting due to increasing political pressure. I ask Vinay about the alienation of the ‘cake’ as a recurring motif in his film. “It is the tragedy of adulthood that you are supposed to eat cake and just carry on. I come from a background of training in fiction. So when you see the cakes being brought into the newsroom during such moments day after day, it seemed too good to miss. It was my filmmaking instinct coming in.” He remarks how it also feels insensitive to humorously talk about it because the cake symbolised somebody’s departure, someone’s lack of employment and he had to insert it with “restraint”, with subtlety. To him these techniques are like the hand in poker, which must be disclosed strategically for maximum effect. “While it is not a complex idea, it was positioned in a way to have this impact which I take great pride in.” The historical connotations of these cakes are not lost on us, Marie Antoinette’s cake comes to mind. Today Ravish and Vinay can joke about their tight budgets, as Ravish says, “If I knew he was making a film I would asked for a costume budget.”

The recurring motif of the film — cake.

I ask Ravish about the quality which stops him from compromising on ethics, from carrying on against all odds; as opposed to the ‘banal evil’ which has overtaken journalists. “It is an everyday battle and you are not always brave. Our society is more conducive to immorality and fraud. It is deeply unethical. Women are worshipped, you know and every woman knows the reality behind this. Even women who do the worshipping day and night know it. You live better in dishonesty. A man who decides to not give in to this ease enters the battlefield. It can be anyone; someone who stands up to his father, saying no to dowry. Everyone wants to commit a small amount of fraud on a daily basis, cutting lines, admissions, appointments; it is all a part of the same mentality.” For Ravish, these are manifestations of a corrosion happening at a much deeper level. When social interactions are so transactional, self worth and self esteem depend upon little else but our utilitarian purpose, giving rise to an unending number of “bekaar aadmis”. “In India’s ecosystem, if you talk about honesty, people abuse you, wait for one misstep to brand you as a thief, a liar, a hypocrite.”

He still has not mentioned the ‘quality’ per se, which kept him firmly on the battleground; when he does, the answer, to say the least, is laughably surprising. “I am a darpok aadmi. I have too many fears and ghosts inside of me.” For someone who has remained at loggerheads with the State for over a decade, we do not know whether to credit his fearfulness or modesty as he continues, “If I do something wrong I won’t be able to sleep at night, I will be restless. The support of my viewers is a big reason.” He mentions the kilos of ghee and sarso ka tel they send him as a token of their love. These moral and sentimental ties keep him committed to the truth. “Sometimes I want to retire from this profession, to separate myself, but there are people in our society who don’t want that. They want certain people to remain in the public eye as the voice of truth. People like me and many others. They offer moral support, they offer gujiyas. These are gestures which keep me going.”

On field with Ravish Kumar. Still from the movie — While We Watched.

We know Ravish as the voice of calm composure on our screens, even in the midst of the most intense trolling. A few years back photoshopped images were being circulated of him with jewellery and makeup on. His response was a master class in how the basest discourse can be elevated by measured responses. He spoke of the dignity of women, the beauty of their adornments and how these images were not humiliating but ennobling. “I have engaged a lot with trollers, those who abuse me. Believe me. I have had hour-long conversations. I tell them that this mentality is not good for the country, for our society. They are becoming criminals. Some people change. They ask for my forgiveness, I do not know them, they don’t need to apologise, but they do. And that is a beautiful thing, I think. Many don’t. I do not need their votes. So I can carry on.” But even for these ‘haters’ Ravish carries profound curiosity and worry. “How do they marry? How do they love? Their proclamations of love to their beloved, to the moon must be lies. Love cannot coexist with so much hate.”

Behind the screen he agonises over his responses. “It is very difficult to know what mistakes I will make tomorrow. Mistakes in names and designations give me sleepless nights. Translating from English to Hindi, some meanings are lost, that pains me. I punish myself. I am not saying this for sympathy. People must understand this profession is not about big stories every two or three months, or breaking news every other day. It is about small acts, small stories, that can come to you while walking down a street. Perhaps if I had the talent, like some people do, of sustaining myself on one story a year, I would do that.”

The moral weight Ravish has decided to carry is not lost on us. “It kills me to say no to people who want me to do a story on their issues. But I have to be firm and clear. I tell them their story is important, worthy of telling, but I cannot tell it. I simply do not have the resources! But I never forget the people I turn down. It makes me more passionate about the stories I end up doing. If I break one heart, I take care not to break the rest.” But YouTube as a medium has changed certain things, he is not sure if it is for the better. “I do not have to leave my house anymore. But then days go by and I haven’t seen anyone, no camaraderie. I miss it even though I have never been too social.”

He gets wistful, “I wish there were more moments of fun and rest in my life but I could not do what I have done, the way I have done it, if there had been. One has to maintain consistency in their work, be incessant, and then announce your retirement after playing your last innings at 35. Pray for me, that I too am able to announce my retirement.” We say we can’t. He is too familiar to let go of. But recently one notices him sharing videos on his social media of vintage cars cruising on American and European highways, sharing flowers, fields and music, and wonders if maybe a silent prayer should be made for a better balance between work and repose. As far as Vinay is concerned, we feel he has just arrived, and what an arrival!

While We Watched now streaming on MUBI.

Words by Ayesha Suhail.