In the kaleidoscopic world of visual art, few figures embody this carrefour of senses as remarkably as Wassily Kandinsky. The Russian painter, often hailed as the father of abstract art, had a unique relationship with synesthesia — a phenomenon where the stimulation of one sense triggers involuntary experiences in another — that influenced his iconic artworks. For Kandinsky, the connection between music and colour was instinctive. He saw each note as a hue, each melody as a dance of shapes on the canvas of his mind: “The sound of colours is so definite that it would be hard to find anyone who would express bright yellow with bass notes or dark lake with treble.”

Kandinsky’s journey of synesthetic expression began with a transformative encounter at the Bolshoi Theatre, where Richard Wagner’s opera “Lohengrin” stirred a vivid visual symphony within him. “I saw all my colours in spirit, before my eyes,” he recalled. “Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.” This synesthetic revelation propelled him to abandon his law career and embark on a path of artistic exploration at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts.

First Abstract Watercolor (1910) in Georges Pompidou Center, Paris, France.

Exploring the Science Behind the Art

Synesthesia, stemming from Greek roots (“syn” meaning “join” and “aisthesis” meaning “perception”), occurs in about 2—4% of the global population, and arises from cross-wiring in the brain. For those who are unable to comprehend this idea of multiple senses, it might seem like an imagined condition. While once dismissed as a mere curiosity, modern neuroscience has revealed synesthesia to be a genuine neurological phenomenon, with implications that extend far beyond the domain of art. Common types include grapheme or colour synesthesia, wherein letters and numbers evoke specific colours, and auditory-tactile synesthesia, where sounds prompt tactile sensations. Chromesthesia is the association of colours with sounds—is particularly relevant to Kandinsky’s work. In chromesthesia, individuals may perceive specific colours when hearing musical notes, resulting in an array of multisensory experiences.

Recent studies have shed light on the neural pathways involved, revealing complex interactions between regions responsible for processing sensory information. One prevailing theory suggests that synesthesia arises from “porous borders” between neighboring brain areas, allowing information to leak across normally distinct pathways. Despite these strides in understanding, synesthesia remains a deeply personal and subjective experience. Each synesthete’s perceptions are uniquely their own, shaped by a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and cognitive factors.

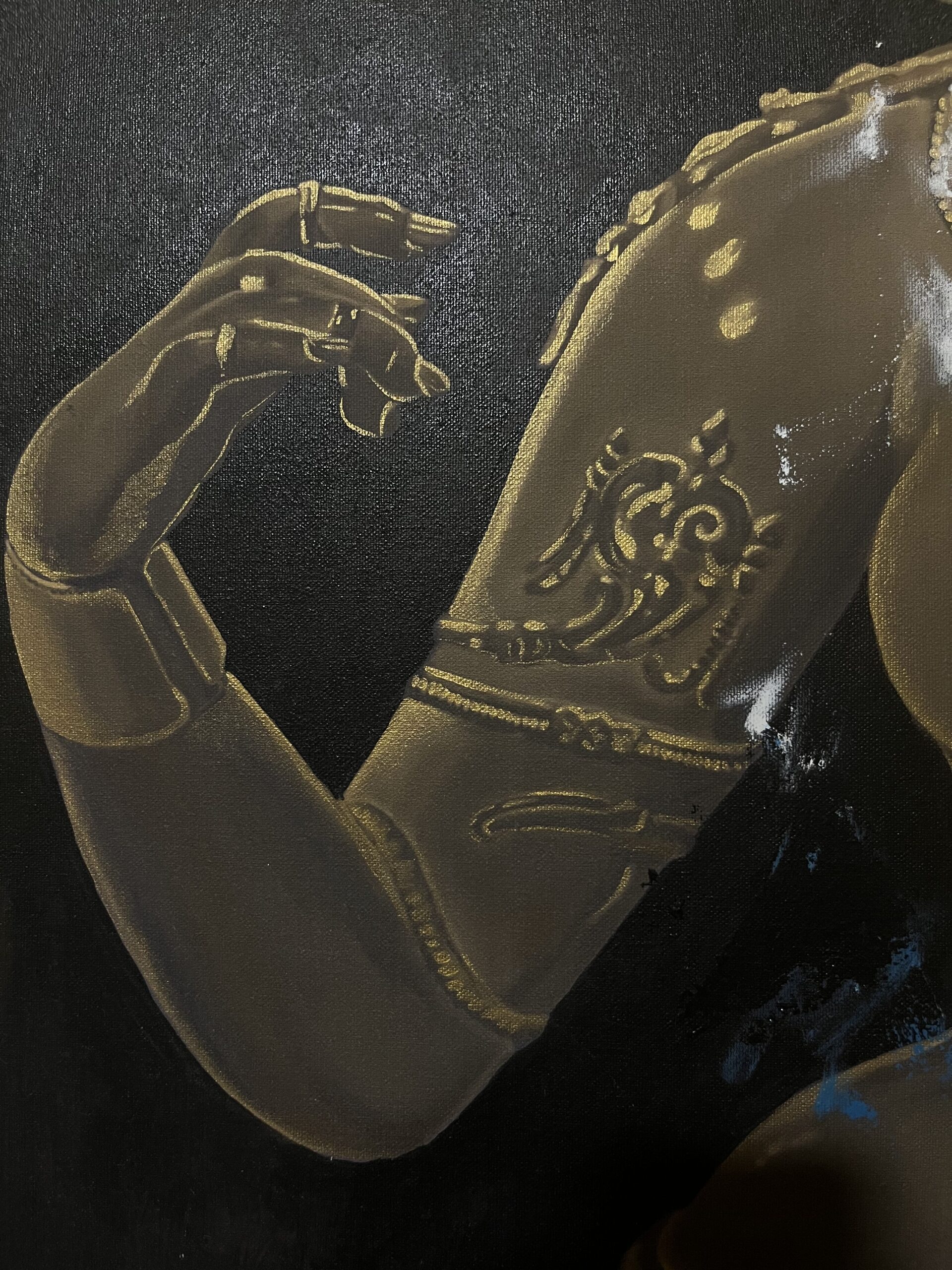

Fragment 2, Composition VII.

Kandinsky’s synesthetic experiences weren’t confined to passive observation; they became the driving force behind his revolutionary abstract compositions. His paintings, such as Fragment 2 for Composition VII, translate his sensory perceptions into dynamic forms and vibrant colours. Integral to Kandinsky’s artistic philosophy was the belief that colour had the power to awaken spiritual truths within the viewer. Yellow, for instance, could disturb, while blue awakened the highest spiritual aspirations. In his seminal treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, he wrote, “Color directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings.”

Can you imagine being able to visualise how one perceives sound? The Russian artist’s deep engagement with music served as both muse and medium for his synesthetic expressions. Inspired by avant-garde composers like Arnold Schönberg, whose atonal compositions rejected harmonic conventions, Kandinsky eschewed representational art in favour of pure abstraction, deploying colour, line, and shape to create rhythmic visual experiences. Titles like Composition and Improvisation reflected his musical approach to painting.

The Yellow Sound

The artist’s exploration of synesthesia extended beyond the canvas. He delved into experimental performance-based expressions, like The Yellow Sound, where original musical scores, lighting, and various media converged to evoke multi-sensory experiences akin to his own.

Improvisation 31 (Sea Battle)

Wassily Kandinsky’s artwork holds varying values contingent upon factors like piece specifics, size, medium, condition, provenance, and current market demand. Displayed prominently at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Kandinsky’s pieces span from hundreds of thousands to several million dollars at auctions. Among his seminal works are Composition VII, lauded for its pioneering use of abstract forms and vibrant colours, and Composition VIII, which showcases his mature abstract style through dynamic compositions and bold geometric shapes. Yellow-Red-Blue epitomises his exploration of colour theory and spiritual symbolism, while Improvisation 31 (Sea Battle) captures narrative and emotion through expressive brushwork.

Many people possessing this neurological condition may not be aware of it, assuming it to be ‘normal’ due to its innate quality or might find it difficult to express its existence to those around them. This is probably why synesthesia is more commonly associated with artistic careers based on research findings, but isn’t limited to creatives. Kandinsky’s legacy paved the way for abstract expressionism, owing to his association of sound with colors, shapes and emotions, and more importantly, his ability to bridge this gap between sight and sound.

To understand it better, check out Play A Kandinsky, by Google Arts and Culture in collaboration with Centre Pompidou.

Words by Aditi Bhaskar.