As the luxury market slows down, there are questions popping up as to what some of the best strategies are to survive. One of them is on what is the optimum company structure – remaining independent, or joining a conglomerate.

Kering knew beforehand that it was going to be a dismal quarter. On March 19, 2024, Kering, the luxury group that boasts Gucci, Balenciaga, Boucheron, Bottega Veneta, Yves Saint Laurent, and many other prestigious brands in its portfolio, sent out a preliminary statement mentioning so. Sure enough, the 2024 First Quarter Report of Kering, which was released on April 23, 2024, stated that sales were down by 11%. “While we had anticipated a challenging start to the year, sluggish market conditions, notably in China, and the strategic repositioning of certain of our Houses, starting with Gucci, exacerbated downward pressures on our topline,” François-Henri Pinault, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Kering, said in the statement.

Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH), which boasts an even larger portfolio of brands like Dior, Tiffany & Co., Loewe, Veuve Clicquot, Pucci, Guerlain, Bulgari, and countless others, reported a 3% organic growth in the first quarter of 2024. However, the growth was sluggish. There is actually a 2% drop year-over-year at LVMH. This sponsor of the Paris Olympics 2024 is on equally rocky grounds.

In sharp, sharp contrast, is Hermès – the (still) family-owned brand. Their revenue grew by 17% in the first quarter of 2024. Brunello Cucinelli, Moncler, Prada, Zegna – all family-owned – showed double digit growth in revenue in the first quarter of 2024. Do these numbers mean something? Is there a trend? Does that mean it’s better to be family owned?

The great ‘LVMH’ merger.

The might of a conglomerate

Bernard Arnault, who was, and is, primarily an investor, saw the opportunity to merge and acquire luxury houses in 1980s. The first step towards this was merging Louis Vuitton – the extremely prestigious leather goods brand – with Moet Hennessy – which was itself a merger between champagne brand Moet & Chandon and cognac brand Hennessy. The rest is history. Since the 1980s, Arnault has been on a steady path of acquiring prestigious brands, making him one of the richest people in the world today. LVMH, at the time of writing this, is valued at approximately USD 424 billion, holding 75 brands. It was valued at USD 500 billion in April 2023.

LVMH has competitors Kering and Richemont. Kering, which has humbler origins as a lumber trading company, went on to revolutionize itself constantly, to finally become the luxury group that it is right now with an approximate value of $43.5 billion. Richemont, with brands like Cartier, Buccellati, Piaget, IWC Schaffhausen, Dunhill and Montblanc under it, is valued at USD 86.25 billion at the time of writing this.

Then there is the Swatch Group, Tapestry (which is overtaking another luxury company Capri Holdings), Puig, and Estee Lauder Companies. None of these are small companies by any measure. So why wouldn’t it make sense to become part of a large group like any of these?

The positive effects of becoming a part of these companies are myriad. The biggest of them is the financial might that a conglomerate can provide. The ability to no longer penny and dime is quite tempting for many creatives, who, though brilliant, are sometimes not so smart with financial management.

Apart from this, there is more that conglomerates offer. Abhay Gupta, Founder & CEO of Luxury Connect, a luxury business consulting firm based in India, and an author, explains, “Pros could be access to global resources, managerial expertise, legal and financial aids, risk mitigation besides local expertise and a common talent pool.”

Adding to this sentiment is Philippe Mihailovich, a Paris-based author, professor, and Co-founder of HAUTeLUXE: “LVMH, Kering and Richemont tend to show enormous respect for founders, creators and craftsmen, and seem to manage most very well. This did not seem to be the case for Lanvin, Buccellati and Kritsia when they were taken over by Chinese-run companies.” Investment funds are the worst culprits according to him. “Bernard Arnault is truly a genius and has a great Medici-sense of respect for creative people and quality,” Mihailovich expands.

Another advantage of being a conglomerate (or being a part of one) is that big groups can afford to hide “what’s going on with individual brands – giving them a competitive advantage” according to Pamela Danziger, a US-based author, researcher on luxury retail, and founder of Unity Marketing. Even Kering reports on only certain brands, she says.

The disadvantages of joining a conglomerate are myriad as well – the most apparent of which is loss of autonomy, which in turn could lead to loss of creative, managerial and brand control, and hence, brand dilution. According to Gupta, integration challenges, limited flexibility due to a rigid operating structure, bureaucracy, slow decision making, loss of independence and eventual legacy loss besides profit dilution are also some aspects to consider.

A tiny detail, which not many think about before starting their brand, is the name. The ownership, or protection of the name, could become a major headache when considering mergers. “One of the biggest downsides is selling your eponymous brand because then you could lose the right to using your name ever again. Many advise creators to name their brands under concept names, just in case. I always advise that name trademarks are always owned by the ‘Name’ and even licensed to their own company. That way, brand and company are separate entities, and investors cannot vote the ‘Name’ out of the business,” says Mihailovich.

As Mihailovich said indirectly, there is a solution to everything. If careful, the cons may not outweigh the pros of joining a bigger company. “One of the things rarely considered is the extent to which a good luxury conglomerate can save a luxury house. Where would Dior, [Louis] Vuitton, Chaumet, Moynat and many others be without Bernard Arnault and LVMH?,” says Mihailovich.

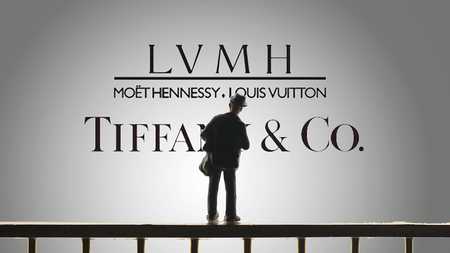

The high drama acquisition of Tiffany and Co. by LVMH

Tiffany & Co. is an ideal example to study. The high-drama acquisition of Tiffany & Co. by LVMH has definitely yielded results for both the companies. In 2020, Tiffany & Co. reported annual revenue of $3.66 billion. And then LVMH acquired the heritage American jewellery brand in 2021 for USD 15.8 billion – much more than its actual value many would say. Since then, Tiffany & Co. grew sales to USD 5.5 billion in 2022 and is forecast to reach USD 8 billion in 2025.

According to Euromonitor International, Tiffany & Co’s strong performance is a result of a new strategy since LVMH took over, which, amongst other things, includes a shift in its advertising by putting more emphasis on social media and celebrities, which has allowed the brand to successfully reach younger consumers. In 2021, Tiffany & Co launched the “About Love” campaign, starring Beyoncé and Jay-Z, while also partnering with both of their NGOs as well. Tiffany’s iconic New York store was fully renovated and opened as ‘The Landmark’, making it not just a store, but also a gallery for artworks. New, chunky collections are targeting a younger audience, while LVMH also plans to open more stores for Tiffany & Co. globally. And if you heard that LVMH plans to make Tiffany’s “less American”, then Anthony Ledru, the CEO of the jewellery company, absolutely denies it.

As Danziger says, “Joining a conglomerate is a very sexy proposition. You are selling your soul in a way. But it’s a big money temptation.”

Flying solo

Many luxury brands continue to operate solo and have fought to keep it so. Hermès is a prime example. Some have created multiple sub-brands and made their brand a group in itself. Giorgio Armani has done that wonderfully well. Of course, keeping your brand with you has many advantages. “Being independent gives a brand flexibility with respect to not only creativity but also collection, pricing, strategic direction as well as staying true to its DNA and values. Authenticity, brand control, agility and adaptability are areas which are in direct control of the brand creative direction rather than the dictate of a large conglomerate which may, out of commercial compulsions at times, overlook the brand narrative. Besides, independent brands retain all profits and have complete control over their financial decisions. This allows them to reinvest profits directly back into the brand and pursue their own growth strategies,” says Gupta.

On the flip side, being independent can restrict growth due to financial and managerial limitations. Lack of experience in faraway global markets, local expertise, legal and cultural frameworks as well as consumer psychology may act as major hindrances in achieving scale and growth. Economic downturns and recessions can make the brand extremely vulnerable to risks, market disruptions as well as market volatility when they are not standing together with a ‘group’. Adding to this, Mihailovich says, “At some point the ‘Peter Principle’ may apply when the founder and or the entire team is way in beyond their competence.” The Principle alludes to the members of a hierarchy who are promoted until they reach the level at which they are no longer competent.

“Creators rarely make great business managers,” says Mihailovich. Danziger agrees with him, citing a simple, scientific fact: “Creativity is driven by the right side of the brain, while success in business is a left-brain function. And creative people are really challenged by that, unless they have a trusted partner who can provide that left brain perspective.”

While flying solo may not be a strategy nailed by many, Hermès has been hitting it hard, time and again. This leather goods brand continues to be run by the original family, with no signs of them giving up the reins. LVMH did try a ‘clandestine’, slow takeover, but failed after Hermès gave a fierce fight. This episode, in fact, jolted the brand out of its languid state.

In 2010, when LVMH started steering close to Hermès, the latter was valued at USD 4.8 billion. A series of steps were taken to make sure Hermès was never again in a similar situation, which included installing Axel Dumas, a member of the founding family, as Co-CEO. Hermès won the battle, and thanks to those measures taken, the brand was valued at USD 30.2 billion in 2023. “Hermès’ steadfast commitment to independence has been a cornerstone of its success, enabling the brand to preserve its heritage, authenticity, and exclusivity while maintaining a focus on long-term value creation and brand stewardship,” says Gupta.

Danziger points towards the high pricing strategy of Hermès to create demand and exclusivity for their products, thus elevating their status, and thereby, their success.

Martin Margiela working with Jean Paul Gaultier as his assistant in the ’80s

On the other hand, Mihailovich mentions their commitment to heritage as crucial to the success of this Parisian brand: “Hermès has had really great designers, such as [Jean Paul] Gaultier and [Martin] Margiela, but have always avoided ‘gurufying’ their designers. The only star in the house is the horse, supported by the craftsmen. The excellent timeless fashion that they produce is more like a quiet gift to their customers.”

So what should brands do?

We come back to the original question. Should brands stay family-owned? According to the Danziger, it’s “pretty definitive that luxury is moving towards ‘conglomeratization’.” However, as with any managerial question, this one has no crystal-clear answer as well.

Danziger goes to the origins of luxury to give a holistic response to our simple yet complex question. Luxury was never a market. It was started by individual, creative geniuses centuries ago, crafting fine and exquisite products. “It is a very attractive proposition to become a part of a conglomerate. As an individual company, you may have some investors who want out, you may want a pay day, and joining a conglomerate is the easiest way to get that. However, it does hurt the creativity and the innovation in the luxury market in the long run. Financially, you get the horsepower [by joining a conglomerate], but that’s not where the creativity lies.”

The past, present, and the desired future of any brand or company is so unique, that there can never be a ‘one size fits all’ strategy. The definition of success, in fact, has changed quite a lot. Apart from the financial juggernaut, there are other factors that need to be considered when understanding a brand’s success today. “In the highly dynamic and volatile market with fast-changing consumer behavior, factors like ESG (environmental, social and governance), DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion), etc., have emerged as major decisive factors. Hence it is very difficult to pinpoint brands that are on the correct path,” says Gupta.

Mihailovich, too, believes that the final objective defines the path. “If you wish to remain high luxury only, it would probably be far better to remain independent for as long as you can, if not forever, if you can afford to,” he says. “Once the house decides to go for wider distribution it gets more difficult to manage and to fund, so the power and knowledge of a larger group could be called for.”

While brands like Bvlgari, Dior, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Yves Saint Laurent, Stella McCartney, and more have found success under conglomerates, Chanel, Prada, Hermès, Giorgio Armani continue to ring success as independent brands. Each brand, therefore, has to find its own formula.

Words by Soumya Jain Agarwal.

Featured Artwork by Pilar Zeta.