In January 1960, a prominent white jazz pianist, Dave Brubeck, garnered widespread attention by cancelling a planned twenty-five-date tour of colleges and universities in the American South. He made this decision after facing the rejection of twenty-two educational institutions that had objected to his black bassist, Eugene Wright, participating in the performances. This is just a small instance of the discrimination black musicians faced, which is particularly ironic given how they played an integral role in birthing and shaping this genre of music.

In the realm of social justice, music has often served as a potent tool to engage and sustain a diverse following for various causes. While social justice is commonly associated with political agendas, the intersection of music and social justice runs so deep in certain communities that it’s now regarded as a fundamental aspect of their cultural identity. Take, for instance, the blues tradition, recognized for its African-American origins in the world of music. Beyond its musical roots, it played a pivotal role in shaping the political consciousness of African-American communities. As jazz emerged and evolved, it provided a platform for African Americans to express themselves artistically and culturally, despite facing systemic racism and discrimination. This musical genre allowed for the celebration of Black culture and identity at a time when many were denied basic civil rights.

A similar dynamic can be observed in the interplay between the free jazz movement of the 1960s and its influence on the development of the black-nationalist movement. These instances illustrate how music and social justice intertwine, sometimes forming an intrinsic part of cultural and political narratives. Notable instances of music being a driving force in social change, rather than the other way around, include the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. One of the most emblematic examples of the reciprocity between musical expression and commitment to social justice can be found in the political protest culture of the United States during the 1960s, particularly within the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement. In these crucial periods, music played a central role in uniting and mobilising people for change.

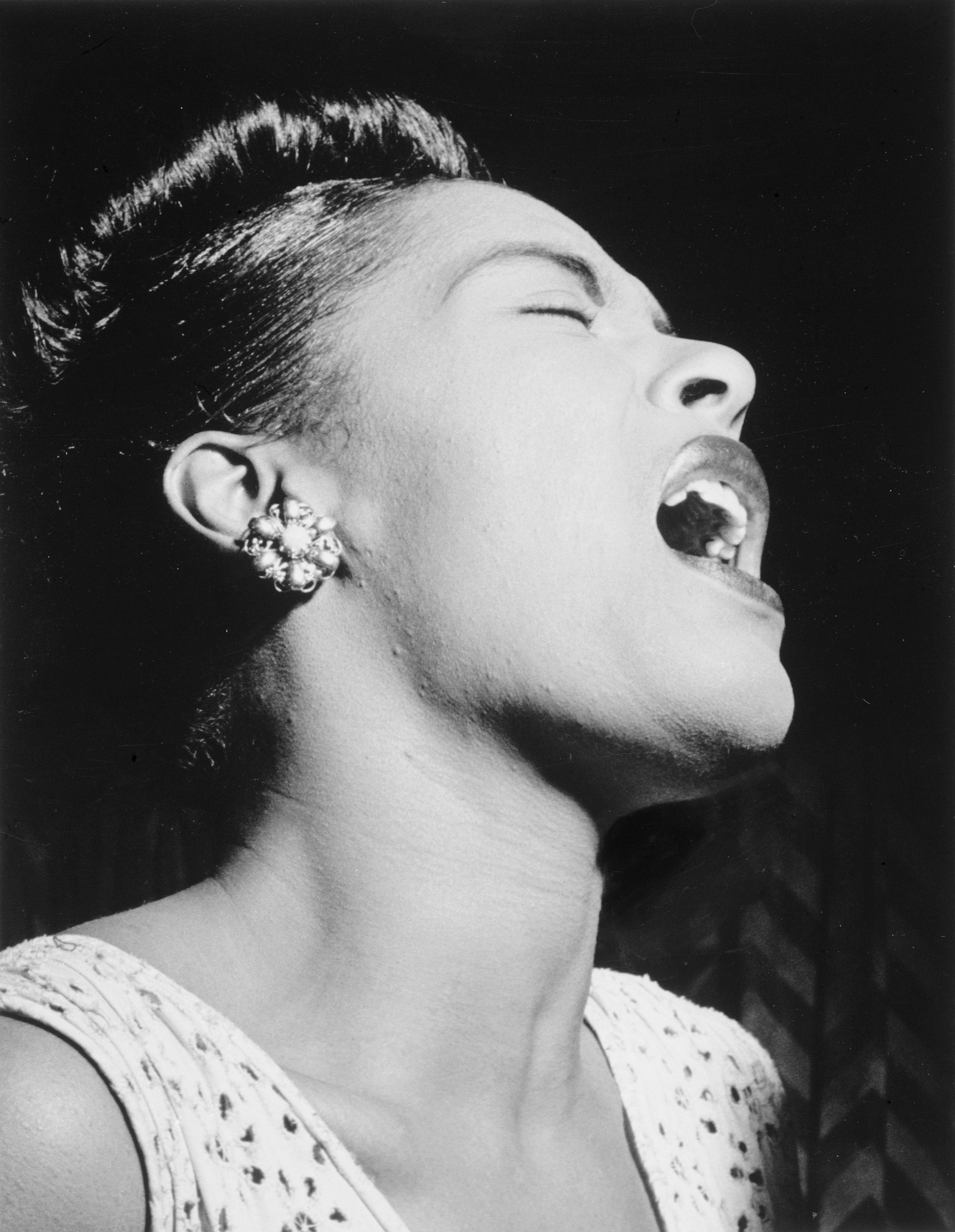

Jazz has always been a means of protest and a vehicle for social commentary. Musicians like Billie Holiday, Charles Mingus, and Nina Simone used their music and lyrics to address issues of racism, discrimination, and injustice. My initial encounter with the profound impact of this musical genre transpired by way of Billie Holiday’s composition, “Strange Fruit.” Recorded in 1939, the track stands as a poignant eulogy to the countless victims of lynching, their lifeless forms hauntingly described as the “strange fruit” that dangled from the boughs of poplar trees. This chilling imagery encapsulates the brutal atrocities perpetrated against the African-American community in the American South. The revelation of the song’s profound message forever altered my perception of music, accentuating its capacity to serve as a resonant vessel for social commentary and a catalyst for collective introspection.

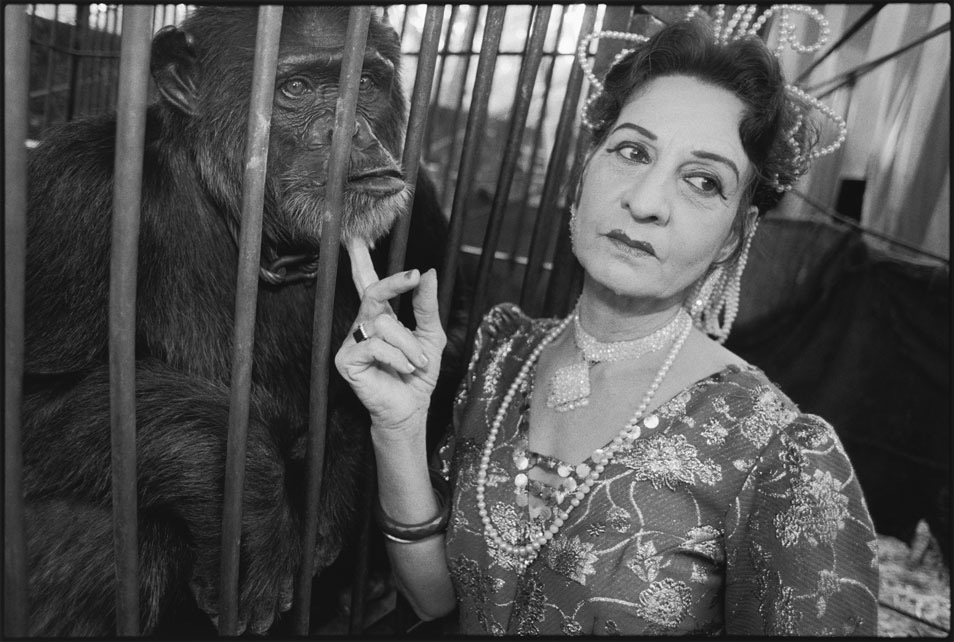

Roy Butler Orchestra at Taj Mahal Hotel, Mumbai

Many artists, apart from Billie Holiday, have used their music to convey important messages. For instance, Charles Mingus’s “Fables of Faubus” from 1959 criticized Arkansas’s segregationist governor Orval Faubus. John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” composed in 1963, mourned the four young lives lost in the bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church that same year. Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” was a passionate response to the 1963 assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers. These jazz pieces demonstrate how music can both remember and inspire social change.

“The social and historical context in which jazz emerged is of primary importance to this discussion. The oppression of slavery fostered a community of ironic understanding that allowed blacks to pass encoded messages between themselves, a practice commonly referred to as signifying, that were frequently aimed at white enslavers. Jazz emerged in the midst of the Jim Crow era, which starting in roughly 1890 imposed segregation on blacks, denied their voting rights, and exploited their labour through sharecropping, practices to which both the Supreme Court and the White House remained indifferent. As a result, millions of southern African Americans migrated to the north and west between 1900 and 1950 to escape the hardship and penury imposed on them by Jim Crow legislation and the legacy of southern enslavement. Black Americans gradually achieved greater freedom by filling labour shortages and joining the armed forces in both World War I and World War II, by organising through such groups as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and by creating music that deeply affected the white population not just in America but throughout the world. The social context in which jazz emerged thus was one in which rampant racism gradually diminished although it, ofcourse, has never entirely disappeared.” writes Malcolm Douglas in his article “‘Myriad Subtleties’: Subverting Racism through Irony in the Music of Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie” published in Volume 35 of the Black Music Research Journal.

Billie Holiday; Mark Pecar

The integration of jazz clubs in the mid-20th century played a pivotal role in the broader civil rights struggle. Prominent jazz venues like the Village Vanguard and the Newport Jazz Festival began to feature racially integrated bands and audiences. This shift not only symbolised a commitment to equality but also fostered a sense of unity among people of different racial backgrounds. Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong were instrumental in breaking down racial barriers within the entertainment industry. They achieved mainstream success, becoming influential figures in American music and culture, while simultaneously challenging the racial segregation of their time.

In the 1920s, Duke Ellington initially gained recognition at the “Cotton Club” in Harlem, a venue with a “whites only” policy. However, within the confines of the club, racial segregation was evident, with black performers restricted to entering through separate entrances and being unable to interact with white patrons. Amid these limitations, Ellington quietly dedicated his efforts to support the NAACP and its advocacy for racial equality during the 1930s. Whether it entailed advocating for equal access for black youth at segregated dance halls or organizing benefit concerts for the “Scottsboro Boys” – a group of nine black adolescents wrongfully imprisoned for a 1931 rape charge – Ellington harnessed his rising prominence as a renowned bandleader to champion a more equitable society.

Jazz found its way to India in the early 20th century, with the first live performance believed to have occurred sometime between 1917 and 1922, most likely taking place at the Grand Hotel in Calcutta. In the ensuing three decades, jazz music gained immense popularity among the upper echelons of Indian society, primarily British and other white Europeans, as well as select members of India’s royal families, industrialists, and individuals patronised by the British colonial authorities. This era now stands as a pivotal chapter in modern Indian music history.

Ma Rainey Georgia Jazz Band posing for a studio group shot in the mid-1920s, with Thomas A. Dorsey at the piano

Initially, only foreign musicians were permitted to perform in venues in Calcutta and Bombay, reflecting the prevailing discrimination that excluded most Indians from both the audience and the stage. However, this circumstance evolved as African-American musicians who chose to stay in India to establish orchestras and perform required the involvement of local talent. Given that Anglo-Indians were more acquainted with Western music and instruments, they naturally became valuable additions to these ensembles. Among the most renowned and influential Black jazz musicians in India during this period were Teddy Weatherford and Roy Butler.

The interwoven history of jazz and its profound relationship with social justice underscores the enduring influence of music as a catalyst for change. Throughout its evolutionary journey, jazz has consistently served as a compelling and emotive voice for civil rights, racial equity, and broader social justice causes. Esteemed musicians have harnessed the artistic and emotional power of jazz to confront discrimination, kindle a sense of unity, and encourage contemplation of key societal issues.

Words by Anithya Balachandran.