Fashion often speaks in the language of spectacle — runways, screens, and speed. But beneath the gloss lies another set of words and expressions: the language of cloth, slow and stubborn, carrying histories within its fibres. For Bhasha Chakrabarti, a textile artist based between New Delhi and New York, this language is everything.

Through Bhasha’s hands, cloth becomes a witness and a guide — slow, deliberate, and profoundly human. Photographed by Rahul Bhagel

“These works are not nostalgic gestures but quiet acts of resistance. Hawaii shaped me profoundly,” she recalls. “Quilt-making there began as a colonial imposition — missionaries taught it to erase indigenous culture. But Hawaiians reappropriated quilting as resistance. A quilt became a double signifier: integration and defiance. That duality stays with me. Cloth can hold both tenderness and rupture.” Materiality, for Chakrabarti, is more than medium — it is meaning.

“We value fabric for its feel against our skin. That intimacy drives me,” she says. “Even paint — what is it but pigment, minerals, earth? I like bringing attention back to origins. Good art should leak out of the gallery and alter how you see the world,” she opines.

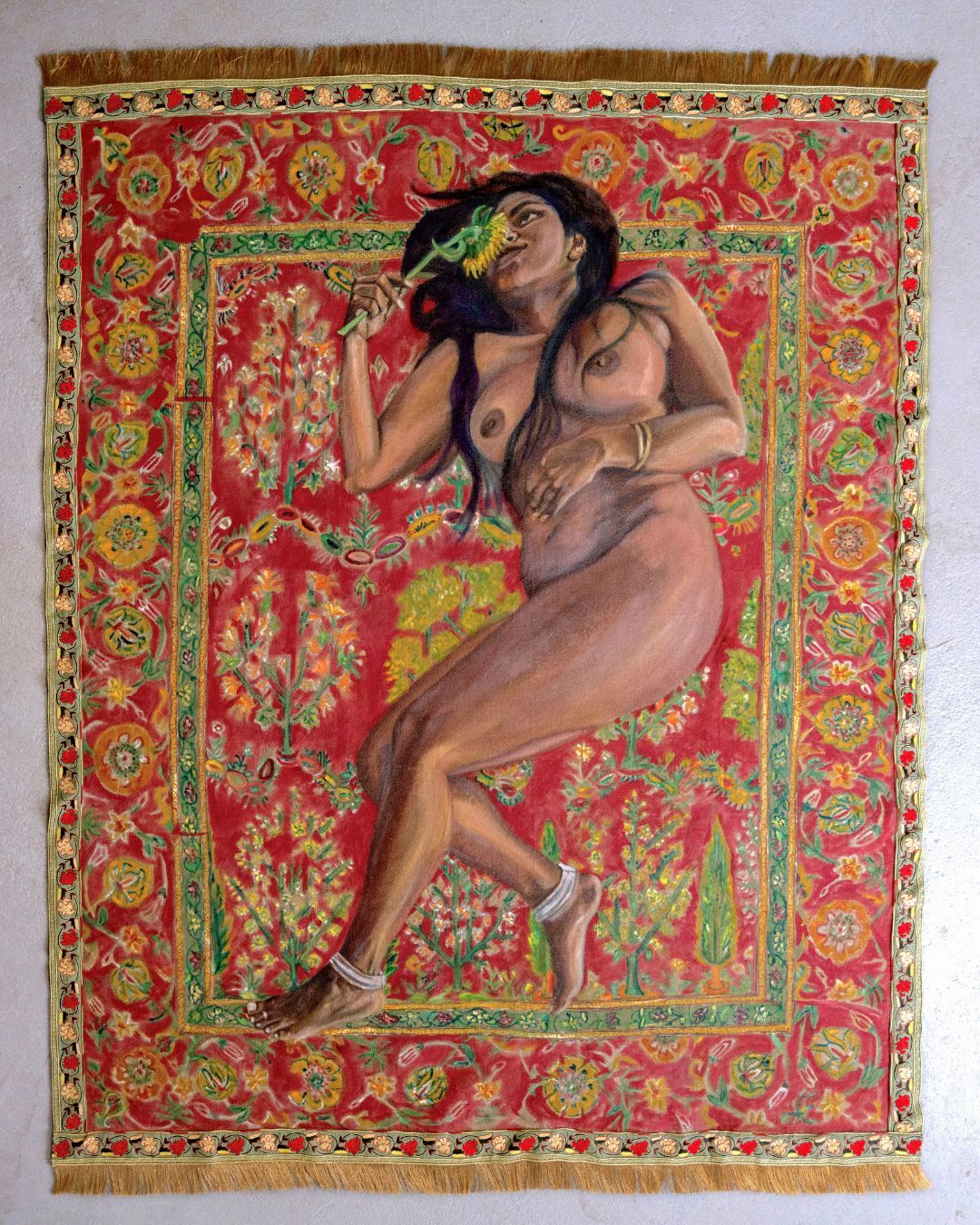

Titled: Karvat, The Turn (Night)

Chakrabarti’s process balances intent with accident. “At Yale, I wanted to study Hawaiian quilting. While digging in the archives, I opened the wrong box and found an invoice for the donation that founded Yale — three bales of Indian cloth sent by Elihu Yale, the then governor of Madras. Not money. Cloth. That changed my work,” she says. It was a revelation, of sorts — reframing her understanding of textiles. They were craft and commodity, but also historical agents of power, trade, and colonial legacy — larger concepts drawn from fresh perspectives.

If concepts drive her, slowness grounds her. Quilts take months, sometimes years. To counter that inertia, Chakrabarti paints daily — like her Antariksha series, born during a Netherlands residency. She says, “I began painting skies every morning. Over time, they started to resemble quilts. Themes overlap without asking permission.”

Though her work sits in major galleries — from Experimenter to Jeffrey Deitch — she resists the market. “The studio is what sustains me,” she says. “Cloth resists capital. It asks us to rethink value.”

In the past, Chakrabarti has collaborated with Hindustani musicians, bookmakers, and fashion designers, and one can say that these partnerships run deep in her work. Her next project with Ashdeen Lilaowala maps the opium trade through Parsi embroidery. “I’m interested in fashion not as trend, but as infrastructure — how it entwines with desire, empire, intoxication,” she says.

1: Titled: The Intoxication of the Flower; 2: Titled: It’s a Blue World

When asked what she’d stitch into the world, she smiles: “That slowness and softness — things we dismiss as fragile — are radical forces.”

In Chakrabarti’s work, these forces gather quietly. Cloth becomes an archive, a witness, a fable of continuity. In a time when fashion accelerates toward the virtual, her practice insists on tangibility, repair, and memory. The future, it seems, might be threaded by the oldest gesture of all: the will to mend.

Words by Shrey Sethi

Feature Image Courtesy JSP Photography