At Kerehaklu, coffee isn’t passed down — it passes through.

Kerehaklu — ‘shelter by the lake’ in ancient Kannada — nestles in Chikmagalur’s misty highlands, where the Thipaiah family has tended coffee for five generations. Here in the Western Ghats, as a fifth generation coffee producer, Pranoy inherited more than just his father Ajoy’s trees — a legacy of temporary custodianship.

“Trees are our form of inheritance,” he says.

(L-R) An expanse of trees at Kerehaklu that impart the knowledge to the land; An attempt to ward off evil from the wisdom. Photographs by David Stallings

When Pranoy speaks of his estate, he never uses the word ‘mine.’ The linguistic restraint reveals everything: This 250-acre fragment of Karnataka exists in defiance of ownership — temporary episodes in its longer memory. “We’re just the most recent chapter,” he observes.

This inversion of perspective transforms how we understand value. Kerehaklu accumulates complexity, each generation adding notes that couldn’t exist without the previous one. In their coffee you taste both terroir and time.

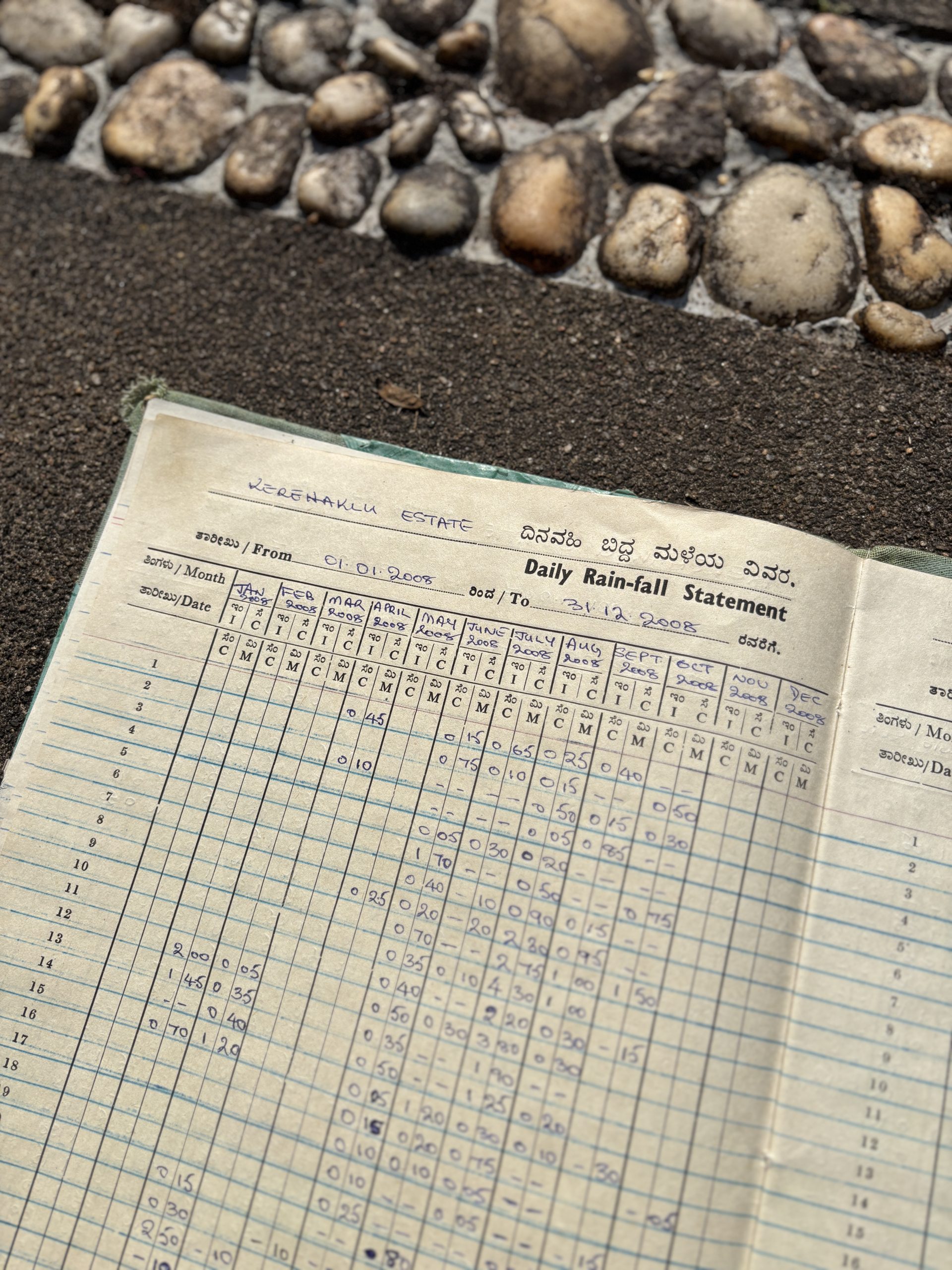

The estate’s archives hold 71 years of daily rainfall measurements, harvests, and observations written in three generations of handwriting. These aren’t merely records, but a form of ancestral collaboration — where Pranoy’s grandfather began sentences his grandson would complete decades later. “We are really good documenters,” Pranoy shares, his voice carrying the quiet pride of someone who understands that keeping records is a form of love.

A passage through time — Kerehaklu’s wonderful documentation of the rail across years

When Pranoy returned to India in 2017 after years away from home, what awaited wasn’t a static inheritance but an invitation to join an active conversation, already centuries in progress. For 18 months, he did nothing but listen — to the land, to the workers whose families had tended these same trees alongside his ancestors, to the historical decisions still expressing themselves in today’s canopy.

What emerges at Kerehaklu isn’t sentimentality about legacy, but a radical reimagining of time itself. The eight varieties of avocado trees planted by Pranoy’s grandfather in the 1970s weren’t intended for future generations — but resulted in a temporal architecture designed to unfold decades after his own lifetime. The diverse canopy that now protects against climate volatility wasn’t created by any single Thipaiah, but through their sequential wisdom.

Kerehaklu eliminated all chemical inputs in 2016 — not as marketing but as the logical endpoint of five generations’ doubt about industrial agriculture’s arrogance. This was a radical departure in an industry where synthetic fertilisers and pesticides had been standard practice for decades. “You can’t just take something that’s been on steroids and suddenly drop all support,” Pranoy explains. “We had to relearn patience, accept temporary drops in yield, and trust that the soil’s natural resilience would eventually reassert itself.” The transition required not just ecological faith but a fundamental recalibration of how success is measured.

The careful selection of the output from Kerehaklu. Photographs by David Stallings

This isn’t sustainability as fashion, but as philosophy. Soil tests now validate what Pranoy’s grandfather intuited through observation alone: Diverse plantings, natural decomposition, and minimal intervention create healthier systems than any chemical regimen could achieve. The recent appearance of a leopard, photographed for the first time on the estate, isn’t just wildlife conservation but a chronological vindication. Along with dozens of bird species never before documented on coffee estates, it serves as living proof that economic productivity and ecological vitality aren’t mutually exclusive — a delicate duet, a reminder of other hands, other dreams. What once seemed like ecological idealism has become a practical necessity. “We are no longer just coffee in bags,” he reflects, understanding that true wealth can be measured in the confidence of wild things to make their home alongside human endeavours.

“Someone recently told me that we’ve made being a coffee producer ‘cool’,” he understates. “But that implies we were responding to the contemporary. We’re actually responding to something much older.” This perspective speaks to a broader shift in India’s coffee sector, which historically has normalised the commodification that strips producers of their stories.

The estate’s true pulse can be felt in its people. In the predawn light, you might find Pranoy working shoulder-to-shoulder with workers twice his age, some whose families have tended these trees for generations. “I’m never giving an order to someone else to do it. I say, ‘Okay, let’s do it together’.” Since 2022, new voices have joined the morning chorus — workers from Assam bringing Hindi to paths where once only Kannada echoed, adding new verses to Kerehaklu’s ongoing song. “They are the backbone,” Pranoy insists, speaking of the multi-generational workforce that rises before dawn to harvest, process, and nurture the estate. “This is not about hierarchy, it’s about mutual respect and shared purpose.” As one longtime employee puts it, “Different languages, same soil” — a diversity that mirrors the ecological variety above ground.

(l-R) Pranoy and his father amongst what their family has achieved — for themselves, the land, and its inhabitants — over the decades; A part of the result at the estate. Photographs by David Stallings

Time moves differently here. The clockwork certainty of monsoons that Pranoy learned about in school has given way to new patterns that demand both resilience and reinvention. “My father’s records show that in the 1980s, we could set our calendar by the monsoon — June 15th to August 15th, without fail,” he explains. “But in July 2024, we recorded the heaviest rainfall ever recorded in 65 years — an intensity that challenges both the land and those who depend on it.”

“In Kannada, we name our rains,” Pranoy explains. “Revati is the first rain of the season — each has its personality, its purpose.” It’s the visceral reality of rainfall patterns that have shifted dramatically in just one generation. The estate’s response hasn’t been merely reactive but strategically adaptive: Expanding their lake’s capacity to capture increasingly erratic precipitation, establishing temperature-controlled nurseries to protect young plants from extreme heat events, and leveraging the different water requirements of Robusta and Arabica varieties to maximise resource efficiency. These aren’t stopgap measures but systemic redesigns that acknowledge a fundamental truth: Yesterday’s certainties no longer apply to tomorrow’s weather.

Pranoy’s father, with the wisdom of those who came before him, which he imparts with those who come after. Photograph by David Stallings

What Kerehaklu offers isn’t nostalgia but prophecy — a glimpse of what becomes possible when we extend our imagination beyond quarterly profits into quarter-centuries. In an economy engineered for extraction, they practice addition. In a world where permanence has become luxury’s rarest commodity, value is measured in the quiet certainty of roots that remember. The most profound luxury, it turns out, isn’t what you can possess but what you can perceive.

At Kerehaklu, time doesn’t just pass — it accumulates, pools, deepens. Coffee doesn’t just grow — it remembers. And what appears at first glance as an heirloom is revealed, upon closer inspection, as something far more revolutionary: A living refutation of the very concept of ownership, a quiet insistence that we belong to the land rather than the reverse.

“I’m just the camera man. This is actually long before me. It’s gonna happen long after me. I’m just standing with my iPhone, and I’m like, if I think it’s cool, maybe a couple hundred other people might as well.”

As evening settles over the estate, painting the canopy in shades of gold, one understands what Pranoy means when he says, “If we don’t tell the world, then no one will.”

This is Kerehaklu, where time grows on trees and wisdom flows like the Revati rain.

Words by Shravni Sangamnerkar.

Feature image courtesy David Stallings.