There’s a language Kansh speaks that exists somewhere between sound and image. In his music, the distinction between hearing and feeling collapses — vocal chops fracture mid-phrase, delays pull time apart at the seams, bass frequencies rise until they’re architectural. The Chicago-based Punjabi-American artist builds his work at the intersection of hearing and seeing, constructing environments where production techniques mirror visual aesthetics. Distortion answers pixelation, delay matches atmospheric gradient, and rhythm finds form in colour and light. His imagery — surrealist, saturated in neon and glitch, steeped in cultural symbols filtered through digital decay — operates as the music’s second half.

Kansh calls this the eer candi era, where every element serves feeling over meaning.

The journey here followed its own logic. Kansh’s early success came through Brown Sugar, a TikTok-viral rooted firmly in hip-hop’s lyrical tradition. His 2021 project Archive 2:Cherry Red established him as a rapper and producer who could craft bars worth dissecting. But somewhere between then and now, the lyricism that once anchored his work began to dissolve into texture. Words became sounds. Sounds became environments. And the visuals, always present and striking, evolved from accompaniment to co-author.

His singles Iluv, uuu, and Superman mark this transformation. These tracks sit comfortably in the growing underground scene that fuses trap drums with glossy, electronic textures borrowed from 2010s pop, all filtered through heavily processed modern vocals. What distinguishes Kansh is how intentionally he blurs the line between hearing and seeing, between narrative and sensation. Each release carries listeners through sonic landscapes designed to make you feel the way things are said, prioritising sensation over literal meaning.

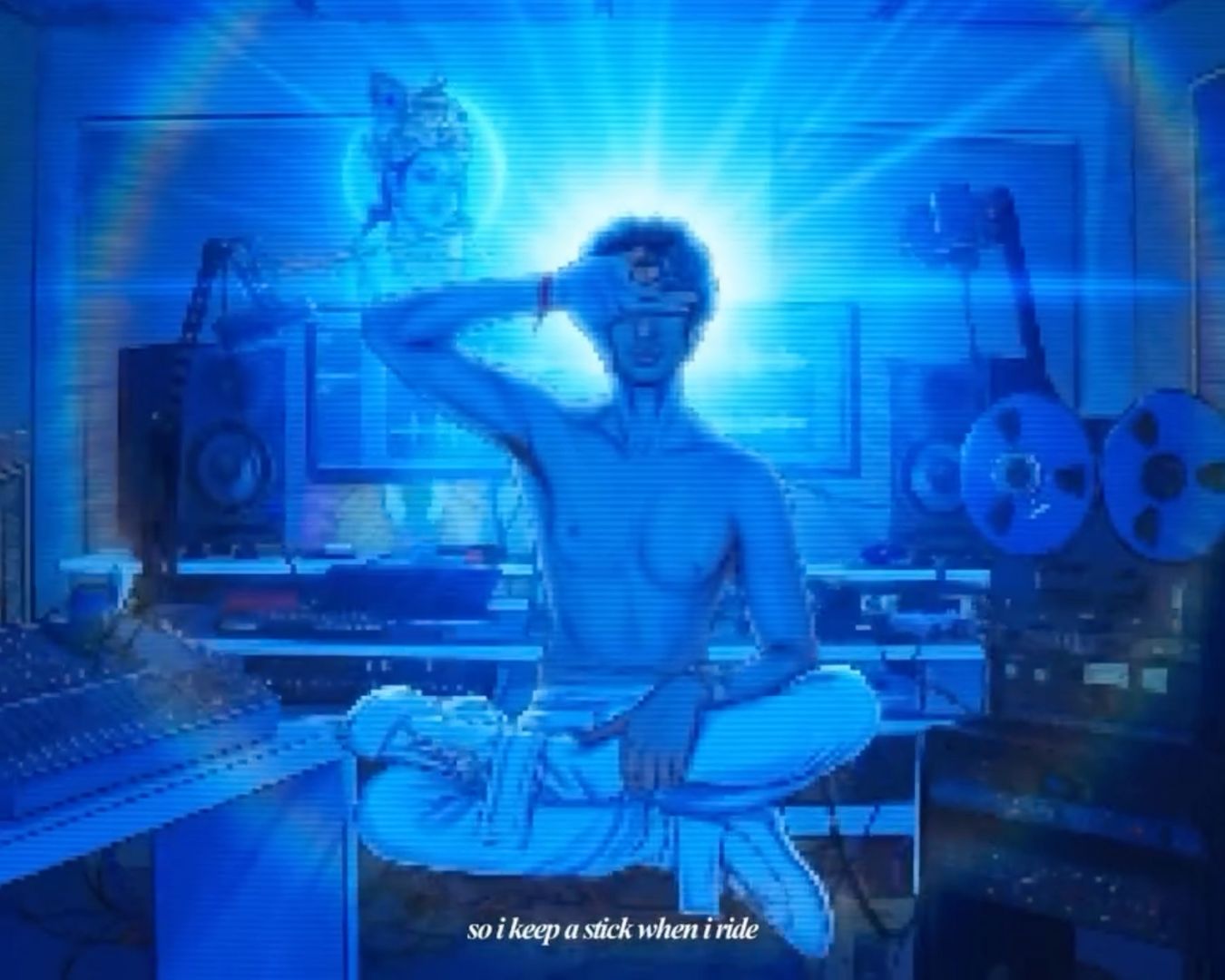

Stills from We Might Be God

Take his collaboration with artist and singer-songwriter Aidn on their recent release Eternity. The track wrestles with permanence and loss, moving between registers.“I spoke to God, she told me it’s my time,” Kansh offers, weaving spiritual seeking into romantic reckoning. The real vulnerability lives in how he submerges these words in production that mirrors the emotional spiral. Lines like “Drawing pictures in my mind, I see uuur face between the lines,” reveal an artist caught in pattern recognition, finding the object of obsession everywhere. The song becomes a sonic rendering of circular thinking, of the way heartbreak loops until you’re counting nights you can’t take back.

The visuals he crafts mirror this approach. Kansh works with heavy pixelation and CRT-style distortion, creating imagery that feels like memory degrading in real time. His aesthetic vocabulary pulls from disparate sources — cultural iconography filtered through digital decay, spiritual symbolism refracted into glitch art, solitary figures positioned against vast, liminal spaces. Light functions as both medium and metaphor: radiant beams cutting through darkness, neon saturation flooding intimate studio environments, silhouettes dissolving into atmospheric gradients. There’s a consistent tone of isolation and contemplation, images that exist in the threshold between worlds, water meeting sky, analogue meeting digital, and tradition confronting futurity. This visual treatment extends his hard electronic beats and R&B vocals into a dimension where sound has colour and rhythm has a form.

What Kansh understands is that sound and vision can occupy the same emotional territory. His production techniques create spatial depth and temporal distortion. His visuals do the same through chromatic intensity, strategic degradation, and architectures of solitude. The stop-motion elements he incorporates add tactility, making the digital feel handmade and the electronic feel human. Together, these choices construct immersive worlds that ask you to inhabit them rather than decode them.

Eternity by Kansh and Aidn

In an era of shrinking attention spans and artists facing pressure to optimise for algorithms, Kansh builds something that resists easy consumption. His work asks for sustained engagement, for viewers and listeners willing to sit inside discomfort, beauty, and strangeness simultaneously. The result is art that exists on its own terms, demanding that you meet it where it lives. And where it lives is somewhere between your ears and your eyes, in that space where sound becomes vision and both become feeling.

Words by Rhea Sinha

Feature Image Courtesy Kansh