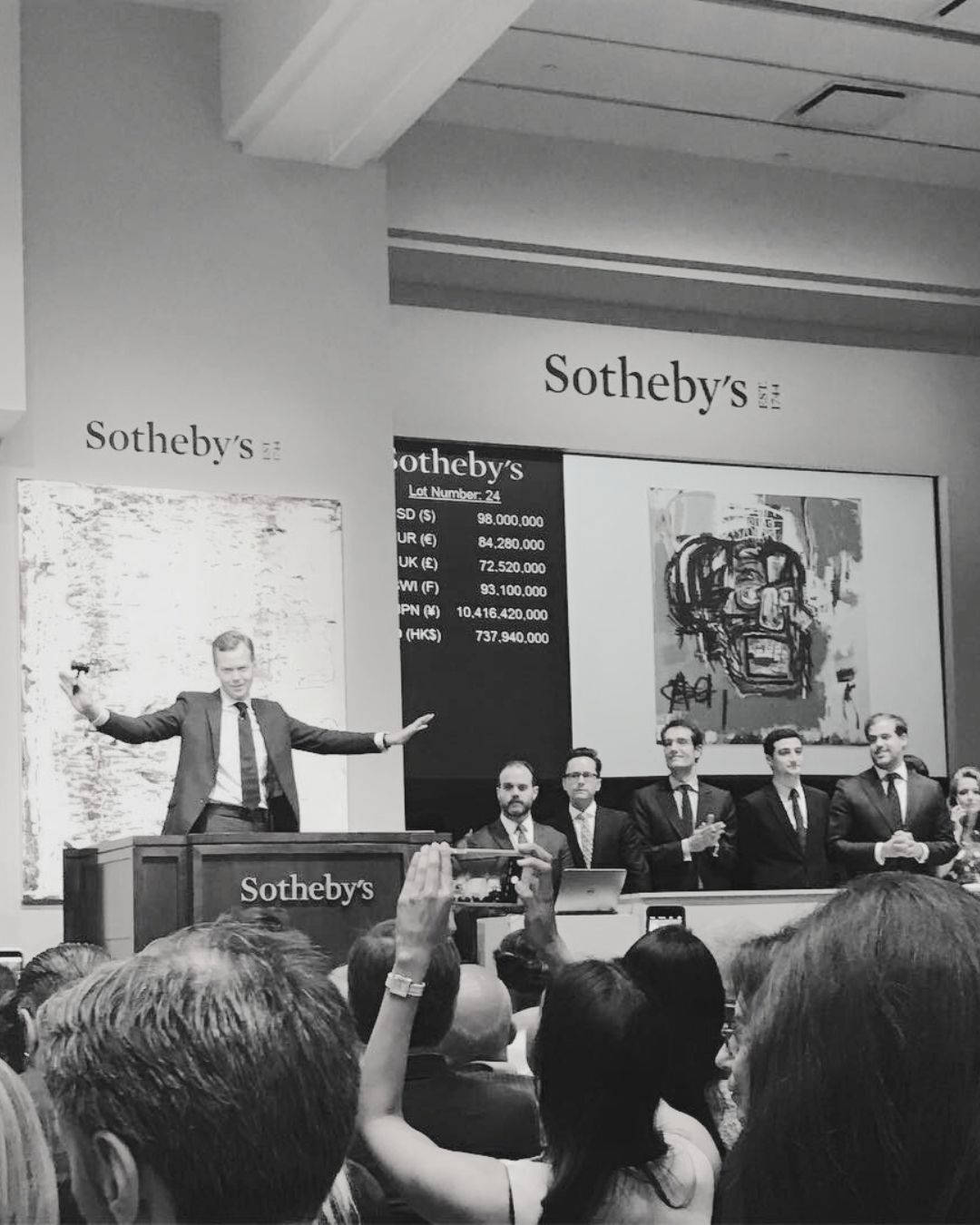

On 24 October 1973, a moment at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet in Manhattan would recalibrate the relationship between art and economics. Robert and Ethel Scull, collectors who had spent a decade assembling contemporary works for hundreds of dollars each, watched as their collection commanded thousands. Robert Rauschenberg’s Thaw, purchased in 1958 for USD 900, went under the hammer for USD 85,000 — art had become a matter of capital.

Five decades later, that revelation has materialised into tangible allocation decisions by the world’s wealthiest. In 2025, high-net-worth individuals allocated an average of 20% of their wealth to art, with ultra-high-net-worth collectors averaging 28%. Contemporary art has delivered returns rivalling investment-grade bonds whilst maintaining virtually zero correlation with traditional asset classes. When the Standard & Poor’s 500 stumbled in 2008 and 2018, art prices held firm, sustained by forces entirely divorced from Federal Reserve policy.

Knight Frank’s Luxury Investment Index crowned art the best-performing passion investment in 2023, outpacing watches, jewellery, and classic cars.

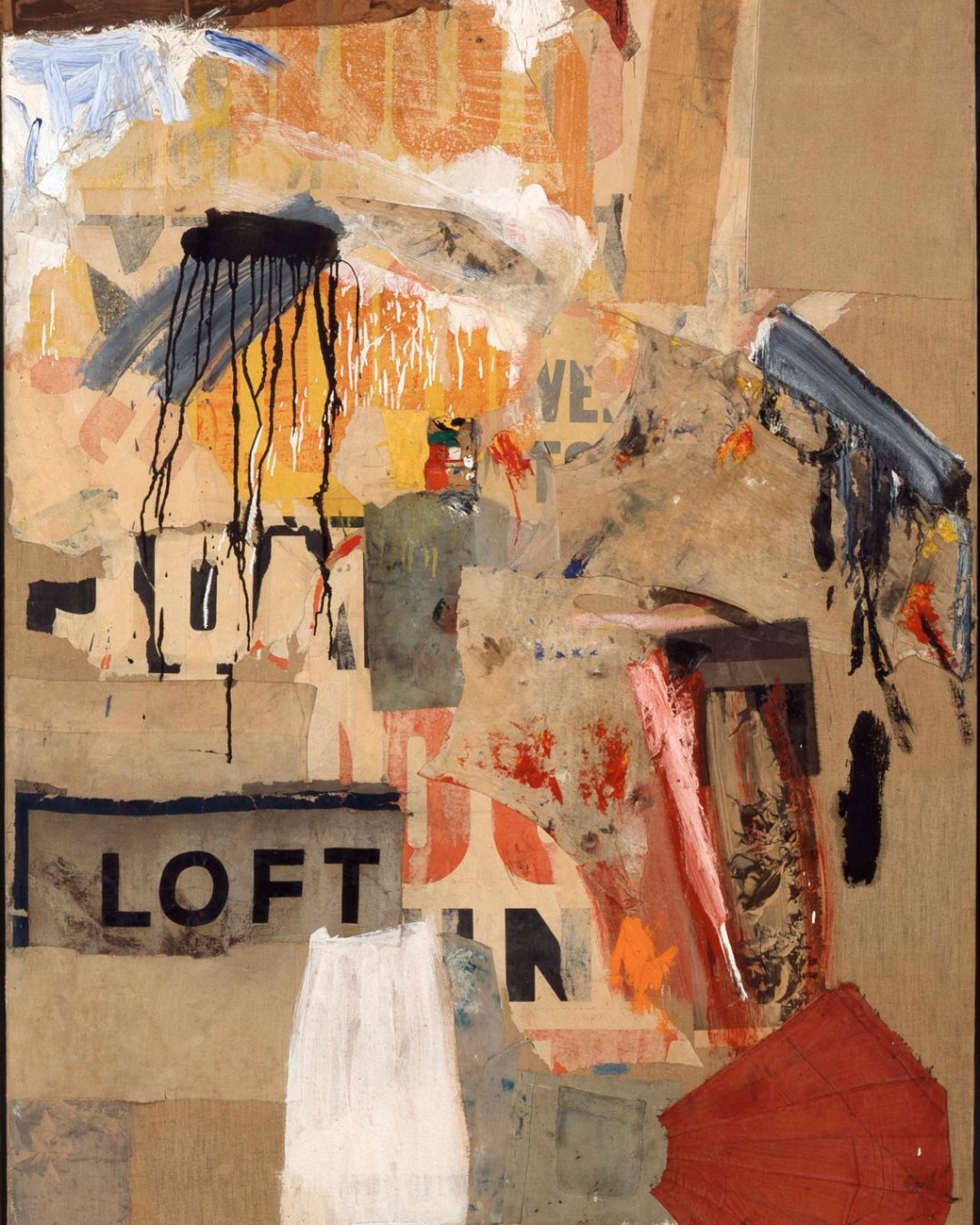

Robert Rauschenberg’s Double Feature (1959) from the Scull collection, sold at Sotheby Parke Bernet in 1973 for 36 times its original USD 2,500 purchase price

Art’s transformation from cultural artefact to investment vehicle traces a deliberate path through institutional innovation. In 1974, the British Rail Pension Fund allocated GBP 40 million to art portfolios — state capital validating an emerging asset class. Throughout the 1970s, the secondary art market expanded as collectors and institutions began applying economic frameworks to cultural objects. By the 1980s, Japanese buyers drove prices to stratospheric heights. Van Gogh’s Sunflowers sold for GBP 22.5 million at Christie’s in 1987.

The auction houses themselves engineered the infrastructure enabling art’s financialisation. Peter Wilson, chairman of Sotheby’s,1958-1980, pioneered guaranteed minimum prices in the 1950s, transforming auctions into glamorous evening events. Presale estimates, telephone bidding, and eventually online platforms democratised access whilst creating transparent price discovery mechanisms. What had been an opaque, dealer-dominated market became increasingly legible to investors.

Art markets simultaneously exhibit wild volatility and remarkable stability. Contemporary art demonstrates annual return volatility nearly five times that of fixed income, yet over longer horizons, quality works demonstrate extraordinary value preservation. A hypothetical USD 1 million invested in 2005 would have grown to USD 5.4 million by 2024, slightly outperforming equities.

From Peter Lindbergh’s Untold Stories exhibit at Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, Germany, 2021

The 2020s have introduced a new complexity. After surging 29% in 2022, art prices contracted 18% in 2024 as high interest rates altered market dynamics. This correction reveals the market’s sophistication: affordable works declined marginally, whilst the top end experienced violent repricing. Art as an asset class rewards connoisseurship, patience, and access — much like venture capital, where a handful of winners generate disproportionate returns.

Despite uncertain economic conditions, high-net-worth collectors maintained substantial art spending in 2024, with positions rising markedly with wealth levels. Strategic advisors typically suggest allocations between 5% and 20% of investable assets. Conservative approaches focus on blue-chip artists with established secondary markets. Aggressive strategies incorporate emerging artists where upside potential proves substantial.

The mechanics differ fundamentally from traditional investing. Buying Monet rather than Manet in 1985 could have meant the difference between transformative appreciation and modest gains. This is why access remains paramount. Establishing relationships with reputable galleries, attending art fairs, joining collector societies — these activities form the core of successful art investment.

Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, sold at Christie’s 1987 in a watershed moment for art as asset class

Beyond financial returns, art offers what portfolio managers call psychic income — the pleasure of living with beauty, the social capital of connoisseurship, the intellectual stimulation of engaging with culture. For Indian collectors, art represents both portfolio diversification and cultural assertion, connecting to heritage whilst positioning collectors within global conversations about value and taste.

Over 10-year periods, art has delivered triple-digit returns, outperforming most passion investments whilst providing diversification benefits unmatched by correlated securities. The collectors who understand this cultivate expertise, study market history, and hold works for decades. Art has proven itself a legitimate asset class by every measurable standard, whilst retaining one essential quality that resists financialisation: it insists on being both investment and lived experience — and that refusal to be purely quantified may be its greatest asset.

Words by Rhea Sinha

Feature Image Courtesy Lock Anderson Kresler