There exists a tacit juxtaposition when stepping foot into the ‘intimidating’ art world—how does one decode art when one lacks the inherent knowledge of what ‘constitutes’ art? And then the age old question: what is art? Who defines it? Who appointed them? Who is them?

Today, we have a diplomatic answer: everything is art. It is the lens through which we approach creativity and expression. With the multitude of new media that have expanded beyond the canvas, art doesn’t exist; it becomes.

An abstract swipe of paint on paper becomes art as much as a slogan shouted in protest of human rights violations. How? Through the journalist who heard the words, through the photographer’s lens, through the collected signboard of the first protestor, and through the sketches of the student who watched from the windows.

Increasingly, contemporary art observes both inner and external turmoil. And this observation is key to humanity, not just to trace the roots of creative movements or the life of the artist, but to document society in a way certain media cannot and will not. Where news must be an unbiased report, art describes suffering. Art injects colour into the monochrome objectivity that dictates modern life.

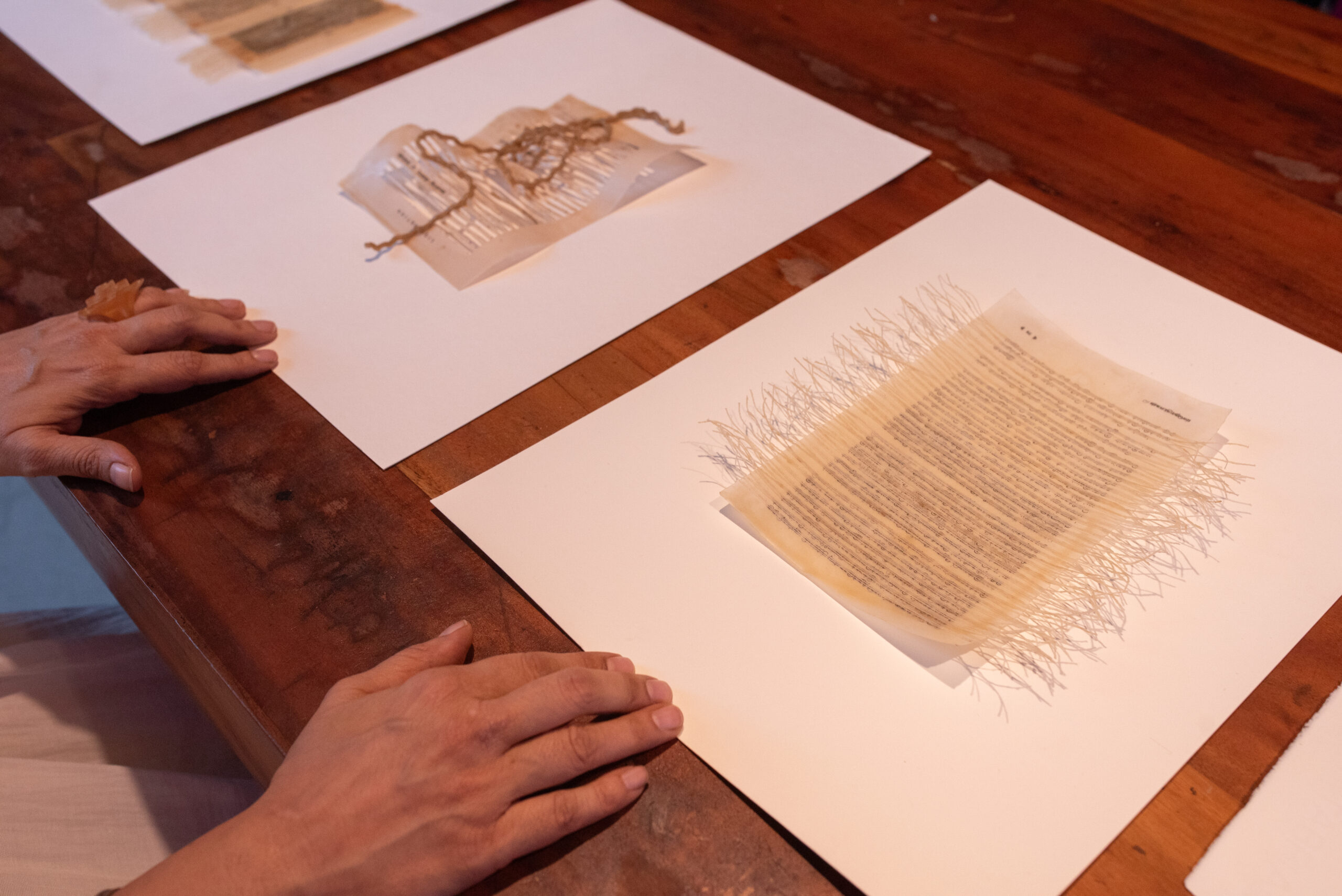

Mumbai-based artist, Mansha Chhatwal’s quiet, delicate works, though simple at first encounter, sit at this precarious junction– observing, documenting, and existing. Chhatwal’s practice deals with the intertwined issues of power and censorship, memory and loss, and creativity and fear, told through banned or censored books and the libraries that house them. Her research based practice, which involves hours of reading books and internalising news, journals, and documents, brings an alternative perspective to art itself. Her art is not for her. It is a visual metaphor that pays homage to the ideas of writers whom she considers braver than herself for their ability to disrupt the status quo. By keeping their ideas alive, she ensures that it is not her own work, but the work of others that endures. In doing so, she invariably challenges the unseen powers that manipulate society to highlight why artistic expression must exist freely.

At a recent networking mixer organised by creative studio Praxis, Chhatwal addressed the challenges of artmaking in the modern battleground of media and law. Seated amongst young creative professionals at Mumbai-based coworking space Ministry of New’s cosy Library (an apt location!), the conversation moved between her own practise and the larger socio-political context of her works. She expertly invited the audience to read into and make their own deductions about the works she carried with her, creating a space for open conversation and interpretation. The chat effectively succeeded into an invigorating dialogue around the impact of censorship on both creativity and society.

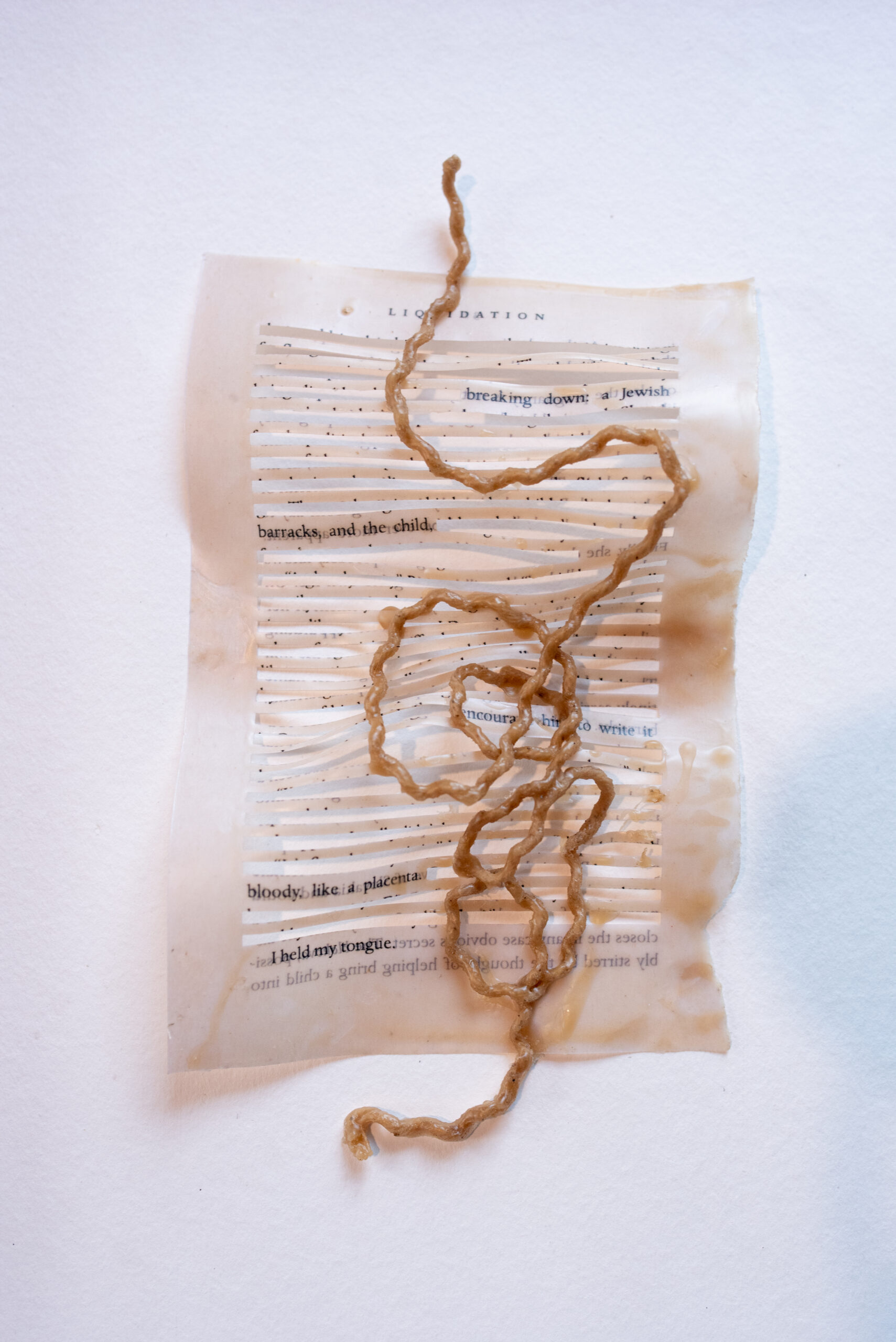

Though her soft-spoken nature might not seem so, Chhatwal is a conversation starter. And where words fail, her art speaks. Her intricate treatment of book pages to obscure and blur words is reflective of her own gentle response to the inherent violence of book burning and the political gagging of writers. In some ways, she fights fire with fire—using hot wax to embalm book pages and converting them into metaphorical ‘candles’ that continue to ignite ideas. Yet the modesty of her final works highlights a simple fact: violence is healed when met with empathetic critical thought.

These continued tensions between medium and message, intention and decontextualization, are what Chhatwal’s practice explores. Censorship, an intangible concept, is made physical with layers of wax, and in being treated so, a complicated topic is made approachable. Though the works cannot be read, she sometimes highlights key words or phrases on the page for viewers to reflect on. In doing so, she emphasises how, taken out of context, words can become tools for misinformation. In an interesting contrast, however, her restrained use of words emphasises that more can be said with less. Her works are simply a spark that thaws viewers out of the mind-numbing passiveness of consumption, and transforms them into nuanced, critical thinkers who might uncover the writers’ true intention.

Through her art, Chhatwal shows a deep sensitivity for writers, journalists, and by extension, other creators, who are persecuted for their work. She empathises with their pain– the loss of freedom, the threat to life, the suffocation of jail– and distils it into a quiet yet poignant piece. The work must go on. The art must live on.

And so, surrounded by activated young minds in a space meant to nurture collaborations and conversation, Chhatwal leaves her rapt audience with a quote from Tamil author Perumal Murugan, whose passionate texts she frequents:

“But finally it rose with a roar and possessed me again—words, thoughts, poetry. And then it seeped in all directions like an unstoppable spring. When I found an opportunity, I wrote the words down on paper. They kept coming forth like never before. Poetry is a great medicine, a rare herb. It was poetry that revived me.”

Words by Vritika Lalwani.

Photographs by Satyraj Singh.