Can a visit to India serve as the inspiration behind one of the greatest jazz standards ever recorded? We are referring to “Take Five” – the extremely well-known track recorded by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, released in 1959. It is instantly recognizable by anyone who may not even be a jazz aficionado. “Take Five” is not named for its connection to the traditional slang for taking a break, such as “taking five,” but to denote how this number takes us away from the here and now due to its sheer rhythm and joyousness. It is because its unusual time signature was not common in jazz at that time. Herein lies the story.

In the 1950s, during the Cold War, the United States Government sponsored tours for American musicians and artists to see foreign countries – especially the newly independent ones. These countries were all perceived as potential targets of communism, and the US aimed to deter these nations from aligning with the Soviet Union by employing American art, music, culture, and movies as instruments of influence.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet consisted of four cerebral guys. Dave Brubeck himself was a pianist and a university graduate from California. Paul Desmond, the saxophone player, was also from the State of California. The bass player was Gene “Senator” Wright – the only black man in this quartet; and the drummer was Joe Morello. It was a time of great ferment in the jazz world since musicians like Bill Evans, Gil Russel, Miles Davis and Charlie Parker were thinking about expanding the frontiers of jazz to give it a solid underpinning in musical theory.

The true maverick in this quartet was Joe Morello. A violin prodigy, he was invited to perform as a soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, at the tender age of 9, playing the lead in Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. He was set to perform with the BSO a few more times until an event occurred that caused him to drop the violin altogether. When he was fifteen, the great violin maestro Jascha Heifetz heard Joe, and invited him to spend a few hours with him. When Morello returned home from that meeting, he shocked his parents by telling them that he was quitting the violin because he believed he could never play as skillfully as Heifetz! He then took up the drums.

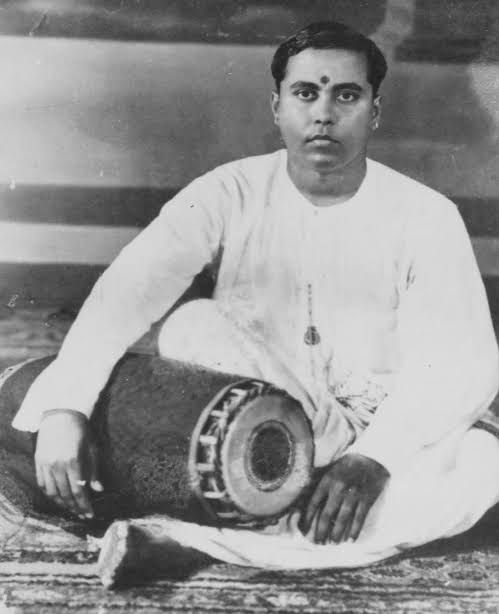

Joe Morello; Subramania Pillai

Morello brought to the art of drumming the same deep thought process that went into his violin playing. This is significant, because at that time, the rhythm section, consisting of bass and drums, was supposed to exist solely for the soloists to do their bit. The drummer would usually deploy brushes on the drums to mark the time. But Morello wanted to do more. Paul Desmond did not like that at all – he thought there was no more to a drummer than time keeping. Morello persisted in his thinking – as a highly accomplished classical musician he was intimately familiar with various time signatures. Jazz at that time had the basic 4/4 and nothing else, so why not try and experiment with something else?

These thoughts were fermenting in Morello’s mind when in 1958, the US State Department arranged a visit to India for the Dave Brubeck Quartet. The quartet landed in Mumbai on a hot April day. The tropical heat managed to warp his piano which led to Dave visiting a local piano store – I suspect it is Furtado’s – and witnessed four men manhandling his new piano! In Mumbai, the quartet met and jammed with the sitar player Abdul Halim Jaffar Khan, after doing a couple of gigs at the Eros Theatre. Morello heard the new time signatures of the tabalchi and his mind went into ferment.

They then flew to Madras – as it was then called – where they had one of the most spectacular encounters which shaped their music. They met the late, great Pazhani Subramania Pillai.

Subramania Pillai – PSP as he was known in those days – was the top mridangam vidwan of the day. A handsome man, immaculately dressed in white muslin shirt and starched khadi white veshti — he was known for his virtuosity, being able to play at several speeds with many complications thrown in. The Brubeck Quartet met PSP at his palatial house in the fashionable Boag Road in Thyagaraja Nagar and got to know each other.

PSP found a discerning and eager pupil in Morello, and proceeded to give him a masterclass in the intricacies of the mridangam and the kanjira, and an illustration of the tala patterns in Carnatic classical music. Morello was mesmerised. He realized that using sticks was insufficient for mastering the Carnatic tala repertoire, so he approached PSP and asked for lessons on the fundamentals of playing the mridangam. Morello subsequently adapted these techniques to playing on his drum set using his fingers instead of drumsticks.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet

L to R: Joe Morello, Dave Brubeck, Eugene Wright, Paul Desmond

A couple of days later, AIR arranged for their jam session to be broadcasted over Voice of America. This broadcast can still be found on YouTube and is fascinating to anyone interested in how cultures meet and fuse. The sonorous voice of Willis Conover can be heard introducing the two instruments – the mridangam and the jazz drum-set. As Philip Clark writes:

“Subramania Pillai opened proceedings with a long and elaborate solo that utilized the mridangam—a cylindrical double-sided drum—to juggle polyrhythmic patterns between his hands, which he coordinated against the bending and sliding of notes as he pressed down on the skins of his drum. As Brubeck and Morello, their ears suitably dazzled, prepared to play with Subramania Pillai, there was an unmistakable air of excited anticipation. The two percussionists set a ferocious tempo, Morello answering Subramania Pillai’s percussive jabs and scrapes by firing rhythms back, his sticks ricocheting against the wooden rims of his drums. Having already learned the significance of 2+2+2+3 for the Turkish psyche, Brubeck wanted to test how compatible the blues and Indian music could be, and the improvisation soon turned into a blues. The opening of his solo was drowned out on the recording by Morello and Subramania Pillai’s sweet thunder, but Brubeck’s piano suddenly zoomed into focus and his light-touch, spidery lines steamrolled toward orotund block chords.”

The musicians left India via Turkey, Iraq and Poland, but the idea of these time signatures was germinating in Morello’s brain. The magic of Indian music had seeped into them and on their return to the United States, the quartet put these ideas into action.

In 1958, the “Jazz Impressions from Eurasia” album carried tracks with influences from Turkish and European music. But the standout track is “Calcutta Blues”. Listening to it, you realise how quickly the quartet absorbed the essence of Indian classical music and applied it to the jazz idiom. Rather than playing one of the ragas, they selected a theme consisting of a set of base notes in sequence – and applied the principles to them. Set note progressions, staying within the selected set of notes, and so on. Morello applied his newly learnt technique on the drums and played with his hands. It is still one of the most unusual and intriguing jazz tracks of all time.

But they were far from done. They spent the following months thinking deeply about their experiences in India and the East, especially around the concept of time in music. It was intended to be a new album featuring specially composed tracks that would demonstrate the impact of different time signatures on the jazz listening experience.

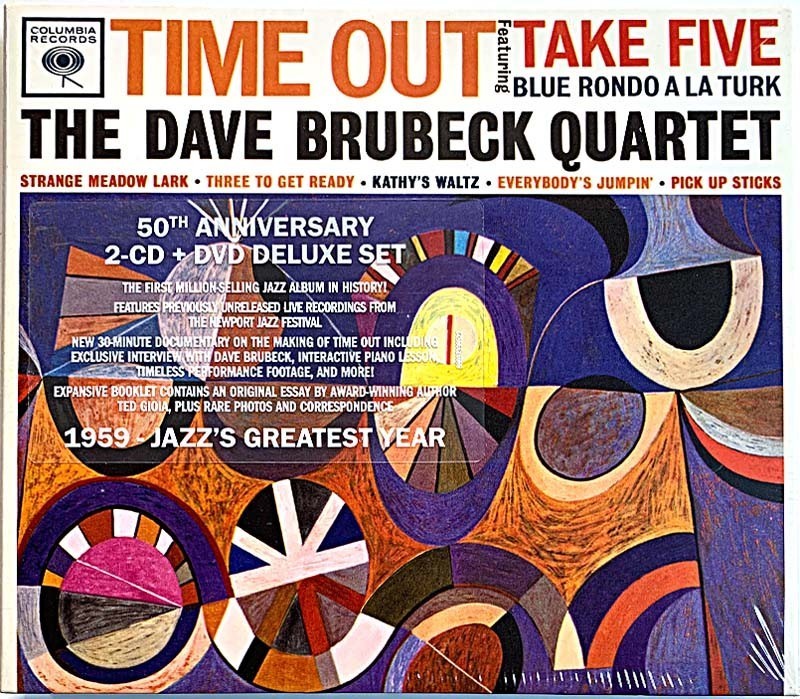

Cover of the Time Out album

When their record company heard about this, they were not pleased. It was the norm for jazz groups to play standards, or at least create something that did not challenge the public’s ear too much. But Brubeck was adamant.

The new album, “Time Out,” was released, much to the discomfort of the record company. One of the tracks used the 9/8 signature of Mozart’s “Rondo a la Turca”. The company agreed to release the album but on one condition. The Quartet had to do a more standard album based on songs from the movie “Gone With The Wind”. The track “Take Five” – which showcases Morello’s drum skills had been burnished in the tour — used the imaginative 5/4 time signature, and was reluctantly released as a single.

Initially the album tanked, confirming the worst fears of the company. But, then an audience looking for new sounds discovered “Take Five”, and it shot up the pop charts. The album took off and became a big hit, setting the stage for further experimentation on time by the Brubeck Quartet. When interviewed in 2010 by the jazz historian Naresh Fernandes, Brubeck remembered the cross-cultural encounter more than fifty years ago with fondness. A few years after Time Out came out, sixties America discovered Ravi Shankar, and the rest is history.

Words by Ravi Rajagopalan.

Image courtesy Discogs, Kane Records, Pillani Subramania Pillai.

Very incisive and useful. I thought influence of indian classical on western Jazz was a 70’s phenomena. Thanks Ravi.

Wonderful article. I love Take Five esp the drum solo. But I had no clue about the history. Or even the name of the drummer! Thanks to this article as soon as I post this, I will look up Calcutta Blues and the duet with PSP.