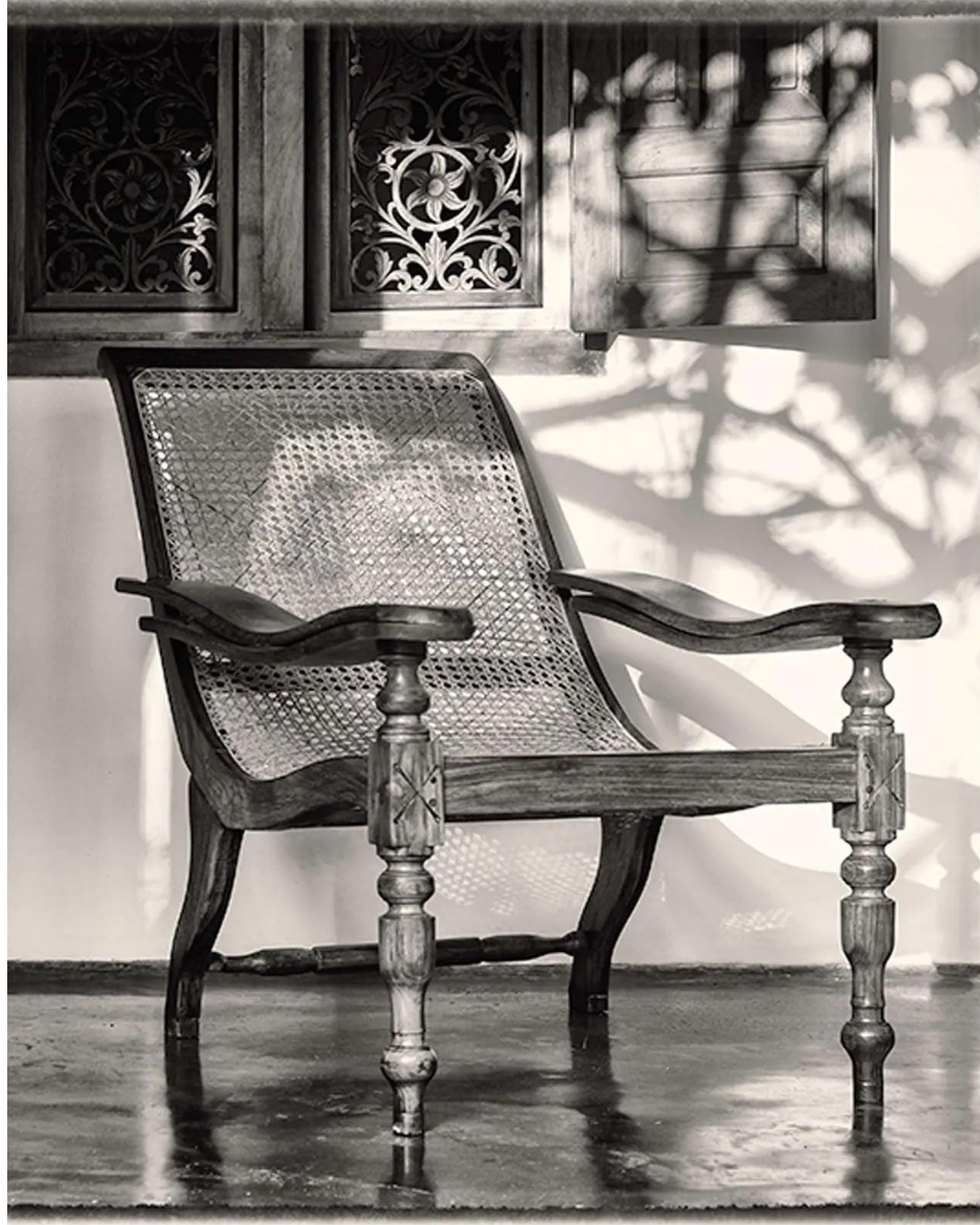

Some objects are portals into the pleasures of the past. One of the most recognisable of these objects is the planter’s chair. It’s unmistakable. It is curvy with an inclined seat of woven ribbons of cane and arms that lengthen into a leg rest. This distinct chair seems to have outlasted its functionality and has since gained the glamour of notoriety and nostalgia.

A little more than a year ago, the Netherlands-based Rachel Lee, an assistant professor of the History of Architecture and Urban Planning was getting ready to come to Mumbai for a research project on exiled artists and architects. “I’d never heard of this chair before,” she says. “But a flippant remark by a fellow historian colleague to ‘look for a Bombay Fornicator’ got me intrigued,” she adds. On arriving in the city, at her first stop – the David Sassoon Library and Reading Room – she sighted the chair. “There was a whole row of them, neatly lined, in the verandah of the reading room. After this, I seemed to see them everywhere,” she recalls. And then, searching for traces of exiled Austrian journalist Charles Petra’s Institute of Foreign Languages, Rachel found herself at the Siddharth College of Arts, Science and Commerce, founded by Babasaheb Ambedkar in 1946, which had moved into the Menkwa Building in 1951, which formerly housed the Institute of Foreign Languages. “There in the library, I chanced upon a planter’s chair that had belonged to Ambedkar himself, and it turns out, it was his reading chair,” she says. “So, I started documenting them alongside this other research project while becoming curiouser and curiouser about this quirky chair.”

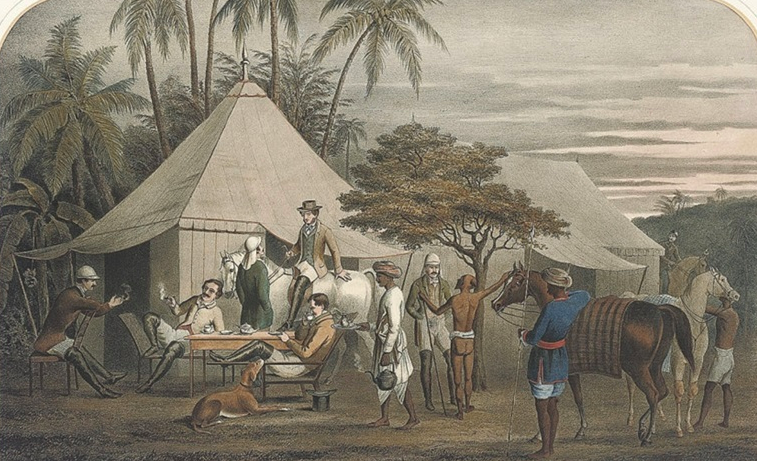

‘The Early Repast’ by British artist Alexander W Phillips, 1851 — where the Planter’s Chair is seen in use by male dominated environments of plantations and military camps (Source: The Antiques Hound)

Interested to know more about it, an architect friend Naresh Narasimhan put Rachel in touch with Sarita Sundar, the Bengaluru-based designer, design historian and founder of design and heritage consultancy Hanno. For Sarita, her motivations were more personal. In the introduction to her book, From the Frugal to the Ornate: Stories of the Seat in India, she begins with describing her grandfather’s charukassela, or reclining seat. She writes of its “dignity and loftiness” and even attributes her encounter with this chair as triggering her “keen interest in material culture and objects” and got her asking questions like: “why they take the shape they do, who conceived them to be this way or that, what gave these ‘things’ agency, and why.”

And thus, their mutual fascination for this item of seating got them working on this Dutch Research Council-funded Planter’s Chair project together. With the dovetailing of their interests and intrigue with this chair, for a year now, Rachel and Sarita have been on the hunt across the country, and the world, seeking out the stories surrounding this striking seat.

Diagram of Planters chair for boar hunting, which was a popular activity for British officers in India.

It’s been difficult to pin down the origins of this chair, and each of the researchers’ relationship with it has helped uncover the possible trajectories to its present form. “Knowing it was called the planter’s chair happened while researching the book. For me, coming from Kerala, it was always known as the charukassela, and while it is associated with plantations and the accompanying lifestyle of leisure, it isn’t entirely either,” Sarita clarifies. “In my context, it was the charukassela or ‘leaning back’ chair, it was attached to stories of the feudal man and the lordly life. The chair was also linked to ideas of exclusion, it was an indulgence that was offered to you, not everyone could sit on it. And even with my grandfather’s charukassela, we sat on it in secret,” she remembers. “The chair’s connection to colonialism wasn’t immediately apparent to me,” she adds.

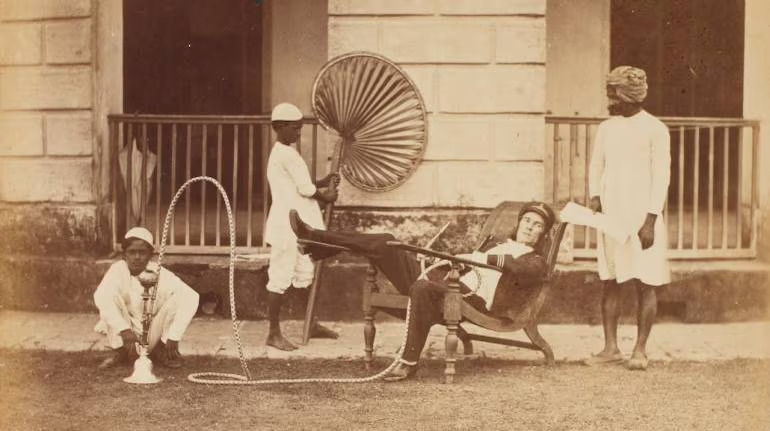

But this changed while researching her book and encountering a sepia-toned photograph of a British Naval officer sitting with his feet up on this chair surrounded by three Indians in his service. And then, she also came across the chair in North India, where it was connected to barracks and army life. “Therefore, there was obviously an association with British officials and the time of the Raj,” Sarita says. “And while initially, it was part of ‘campaign furniture’, so it was foldable with a canvas-cloth seat by the British officers but as they settled down in India, the materials of the chair took a more ‘settled’ form too.”

(L-R) Planter’s Chair in the Bengal Presidency in the late 19th Century, unidentified photographer (Source: Sarmaya Arts Foundation); The Morning Shave, Higginbotham & Co, Madras and Bangalore.

But pinpointing “who first had the idea for the design of this chair” has been “like looking for a needle in a haystack situation because generally chairs aren’t objects that are archived in museums. We’re lucky if we are able to find evidence of this chair in text or images or as an object” Rachel says. “We found a design from China that was called the ‘Drunken Lord’s chair’ from around the period of the Ming Dynasty which has similar features. And looking through prints and engravings from the 19th century, which depict colonial scenes, we often see men with their feet up on the arm-rest on a verandah or with their feet on foot-stools – they clearly seemed to be an inclination to put one’s feet up and at some point, there was a chair designed that allowed the individual to do this,” she explains. “And also, if it was a colonial design, our research has shown that it more likely appeared first in the West Indies rather than India, but we’ve also found evidence of it in South America, and across previously colonised parts of the world. So, the planter’s chair isn’t just a leftover remnant of British colonisation.”

Though over the centuries, the chair’s context has moved on from one of privilege. “Of course, we found this chair on verandahs but people also have them in their bedrooms, we found them to be used as ‘public chairs’ in old offices, but most surprising for me was spotting it in a chapel in Lonavala,” Rachel says. “Why would one ever need to sit like that in a chapel? With one’s feet facing the altar? There’s something so irreverent about this chair, it isn’t very demure,” she adds and laughs. “We’ve come across these chairs being used in an old Parsi hospital for patients to rest and recuperate because it helps the lungs open out,” Sarita adds.

(L-R) Rachel Lee’s first sighting of the planter’s chair on the verandah of the David Sassoon Library and Reading Room in Mumbai (Source: The Planter’s Chair Project) ; Planter’s Chair at Nisala Arana Hotel Sri Lanka (Source: The Past Perfect Collection)

The persistence of this chair speaks to the many qualities it is able to evoke in the sitter and the owner of it. “There’s something about its form, if you see it as children, which is a good indicator, we are curious about it because of its odd shape,” says Sarita. “It’s also quite contradictory in the way it makes the sitter feel while they’re in it. One can feel powerful but also vulnerable, one is exposed, one can’t immediately spring to one’s feet, it’s actually quite a scramble to get out the chair,” she adds. “Some people have said, they can’t actually relax in this chair because the posture doesn’t allow for reading unless one sits a little higher or holds the book up with their elbows on the arm-rests. It isn’t universally appealing but it’s definitely a conversation piece.”

“It acts as a time-machine. Even a chair of similar vintage doesn’t have the same effect. One might be able to appreciate those chairs for the skill with which they were made but no other chair recalls another time and place quite like the planter’s chair,” Rachel adds.

Follow the research project on their Instagram page, here.

Words by Joshua Muyiwa.

Feature image: A planter’s chair kept as an artefact at the Netherlands Open Air Museum in Arnhem. (Source: The Planter’s Chair Project)