It was 8:26 PM on the 24th of July, 2024. The sun was about to set behind the vast, wind- swept steppes of Mongolia. I sat on a cliff, overlooking Lake Olgii from a distance, my eyes fixated on the horizon where the blues of the sky and the water fought with the looming storm and the sun, each trying to tear the other apart every fifteen minutes.

I had been advised to stay far from the lake as a woman. No, it wasn’t just another patriarchal joke, but the legend of Erdene and Baatar — the lovers’ spirits said to reside in Ogii, reunited in the afterlife. Some versions of the tale suggest that the gods were jealous of their love. Others believe that the storm which claimed their lives was a consequence of the woman’s family’s disapproval — possibly due to a long-standing tribal feud. The couple, refusing to be torn apart by the forces of nature or their families, decided to flee together, seeking refuge near Lake Olgii.

But the raging storm over the lake swallowed Erdene, and Baatar — in his attempt to save her — was never found. It is said that the spirits of the lake took pity on the lovers by transforming their souls into eternal forms. Some say Erdene’s spirit became the lake itself, while Baatar’s spirit became the winds that blow across the wild steppes.

Today, the lake is considered sacred, and the nomads of the region believe that women should never disturb it; for fear of suffering the same misfortune in love that befell Erdene. Such is the hold of shamanism over Mongolian imagination. I bought into it for a moment. Mongolia; a metaphysical battleground across space and time, a land where the spirits of ancestors echo with the living. A 1.5 million square-kilometre Ouija board!

It is a land where the earth hums beneath the gallop of hooves, and the horizon mimics the endlessness of time — where the past and present merge into a singular, fluid moment.

A country infamous for its great leader Genghis Khan and his exploits, Mongolia’s legacy is often painted in broad strokes of empire-building, conquest, and the fierce will to dominate. The world remembers the fearsome Mongol Horde, sweeping across continents, dismantling empires, and creating the largest contiguous empire in history. But it is the heart of Mongolia that beats with a quieter, more enduring power — one shaped by the pure submission to nature and its might. Here, the air is thick with the songs of herders, warriors, and shamans, but what lies ahead is still to be determined.

In this land of moving contradictions, we set off to find our hosts for the night in a van from the Soviet era, travelling from Ulaanbaatar — the capital city of Mongolia.

For more than two millennia, nomads on the Mongolian steppe have lived in delicate balance with the land, herding livestock and adapting to nature’s rhythms. After five hours of driving toward the heart of the country, we came across a couple of gers (traditional portable dwellings made of wood, animal skin, and felt) in the Elsen Tasarkhai Dunes, where we met Bor and his family.

Gers in the vast landscapes of the Mongolian steppe.

Photographs from Vishwa’s personal account

Bor, the head of the family, was riding a horse, gathering his fleet of sheep and directing them back to camp. He invited us into his ger and his wife greeted us with a bowl of steamy salted milk tea. There was a quiet grounded energy about them, steady and unhurried. Bor’s rugged demeanour — a controlled toughness while riding the horse — was juxtaposed by his shy mannerisms on ground but there was a quiet pride in his smile.

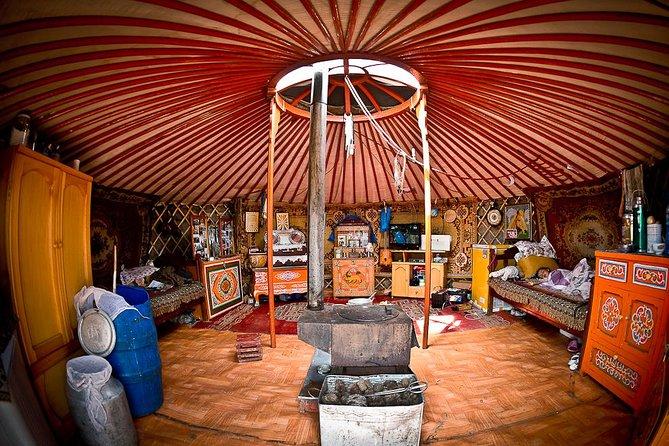

The interior of the ger was steeped in bright orange, with wooden furniture corners forming gaps against the curved walls. It was decorated with meticulously handcrafted rugs, stitched together using hand spun camel hair. The walls of the ger were lined with stories of their ancestors, every available surface put to good use. Much of it seems to have stayed the same from generations, with the exception of the satellite TV flickering away in the corner. I could recognise a similar pattern scattered across the fabric that covered the ger from the inside, the one on the door, on the furniture and bedsheets. It appeared to be a geometrical infinity sign juxtaposed with fluid floral patterns. It was the infinity knot on the door of one ger, intertwined with clouds against a beautiful green surface, that caught my eye — almost announcing, yet renouncing, their claim on this land.

“It’s the eternal knot,” Enkhjin said. The motif can be traced back to Tibetan Buddhism, which made its way to Mongolia through the Silk Road during a time when the country was seeking societal healing. Today, the majority of the population is Buddhist, with roots deeply intertwined with shamanism. The knot represents the perpetual nature of existence and the cycles of reincarnation that Erdene and Baatar, in their eternal bond, took advantage of — a cosmic harmony.

We ended up staying the night with Bor and his family in their guest ger. The first question he asked us was if we knew the song, “Jimmy, Jimmy, Jimmy… aaja.” The western ideology-censored, war-sick media in the USSR had paved the way for Bollywood to reach the nomads in the heart of Mongolia. Their two daughters found us entertaining enough to not sit in front of the television tonight. After a strong cup of airag (fermented mare’s milk), we called it a night.

Nomadic families are generally part of the larger tribal or clan-based groups. They move with the seasonal cycles and vegetation to survive the extremes, providing for their livestock. Herders were once entirely dependent on their livestock for everything — from food and textiles to insulation, farming tools, transport, and business. It helped them maintain a holistic lifestyle that is circular in all aspects. Bor and his family own goats, camels, sheep, yaks and horses. The animals provide meat for food, milk for dairy products, skin for leather and insulation, fur for making rugs, felt, and other textiles, and horns for creating tools for farming and everyday life — much like the lifestyle of nomadic herders in present-day Ladakh.

If you think about it, several parallels can be drawn between the two: sparsely populated regions in high-altitude terrains, harsh climates that gave rise to self-sufficient communities of nomadic herders who adapted Buddhism, all while maintaining their Stone Age traditions in the age of space-age technology. Perhaps this is our only hope in a Kafkaesque world!

Fluid and self-sufficient, nomadic herders move in harmony with the changing seasons of the land.

In our daring effort to reinvent ourselves, as each passing trend encroaches on our sense of self, we book our tickets and set out to find that one unadulterated corner of the world — only to ruin it by attempting to make sense of it with our skewed sense of normalcy. I felt liberated while travelling through Mongolia, even metamorphosed. But this liberation comes at a cost — the cost of exposing a culture deeply rooted in the wisdom of its ancestors to forces intent on capitalizing on every last piece of land, every person, and every effort. Being exposed to bodies steeped in the germs of a modern capitalistic realm has already begun to alter the face of Ladakh, sparing only the most remote villages. The same fate seems inevitable for Mongolia. The transition may be slow, but it is becoming increasingly evident. Capitalism has found its way to profit from the world’s last truly nomadic realm.

Mongolian cashmere goats produce a luxurious undercoat of fine fibres, traditionally used to craft garments suited to Mongolia’s harsh climate, particularly during the frigid winter months. The ancient Silk Road, which passed through Mongolia, was one avenue through which cashmere gained international attention, as traders sought high-quality wool to sell to markets in China, Persia, and Europe. What was once a tool for a self-sufficient ecosystem is now rapidly capitalized upon. Seventy percent of Mongolia’s once biodiverse grasslands have been degraded from goat grazing to meet the increasing demand for cashmere. Although this demand has provided a stable income for some herders, it has created a wicked problem.

On one hand, it aids in maintaining their way of life, offering security and assurance. On the other hand, the steep rise in demand means that this cannot be sustained indefinitely. Overgrazing and forced breeding are threatening pastures with slow death, leading to environmental degradation. The rising demand for cashmere is linked to debt cycles, poor social outcomes for workers, raising temperatures, land degradation, and the endangerment of native species. Nomadic herders, feeling obligated to contribute to this industry, are negatively impacting their surroundings.

Dzud, a term for an extremely harsh winter, is another wicked problem they face, exacerbated by first-world countries and their exploitations. Extreme weather has made survival in the old ways increasingly difficult. For the local economy, which depends on this way of life, dzud can mean food and economic crises. Many nomads who lose their herds in these winters will have no choice but to migrate to cities. The social and psychological anaesthesia that follows is a loss for us all — a loss of collective knowledge on how to exist and thrive against the looming emptiness of modern society and its technological advancements.

The unforgiving chill of dzud.

We continued our journey through central Mongolia for the next fifteen days, driving through its empty canvas interrupted only by the wild, untamed gallops of horses. We ended up staying with the herders for most nights, scraping together some form of a complete meal, and lending a hand with chores. We spent our evenings on horseback, racing across the open plains to round up cattle and direct them back to the shelter. In that fleeting time, the boundaries blurred, and this untamed land was ours to share.

The horse, the endless sky, and the wind — symbols of a culture forged in the fire of conquest — remain present, but now they echo with the footsteps of what a capitalist would call ‘progress.’ The world around us is moving at an unprecedented pace, but these nomadic herders, the living embodiment of resilience, stand as a symbol of cultural endurance — one that, in an age of globalization, must be preserved and protected.

In a world increasingly driven by artificial progress and disconnection, perhaps such cultures offer the last remaining hope for a more grounded, meaningful existence. But preservation of these cultures and systems does not lie only in the safeguarding of land or customs; it lies in the stories we tell and the tales that live on long after our existence. The stories that can be called upon by the shaman in a distant land, seeking guidance for a wayfaring stranger.

Words by Vishwa Patel