“You can see all the lines of my hands, even the faintest ones,” Ritu says to me, holding up a hand sculpture to her webcam. The multidisciplinary artist is in her Glasgow studio, moving around, showing me pieces that span several mediums – a mix of clay, metal, silicone, and more — all peculiar forms, resembling fractured anatomical lumps. But what’s recurring is the feeling: we are inside a live, unfiltered conversation, filled with hesitation, sidebars, and small bursts of clarity that arrive mid—sentence.

The hand she shows me is dense and unfinished. The fingers are curled slightly, marked with lines and folds. “This is the first time I’ve properly delved into casting,” she says. “I’ve been against it in the past. It has always felt too clean, quite formal. However, for this specific new sculpture in process, it made sense. I wanted it to feel real, not a gesture or a suggestion, but a rigid form.”

Ritu, who was born in India and now lives in Glasgow, often speaks of her work as a way of making psychological states tangible. Her sculptures, exhibited in cities like Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Moscow, tend to hover between organic form and abstract tension. In recent years, her practice has been recognised with the Gilbert Bayes Grant (from the Royal Society of Sculptors) that supported her degree show in 2023, as well as a commission from the Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival in 2024. “I’m interested in the patterns that emerge during mental decline,” she says. “Not just my own, but others’. It’s not just personal, it’s shared.”

Titled: ‘Peek-A-Boo/how do you make your toast?’

(commissioned by The Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival in 2024)

Photo – Alex Woodward

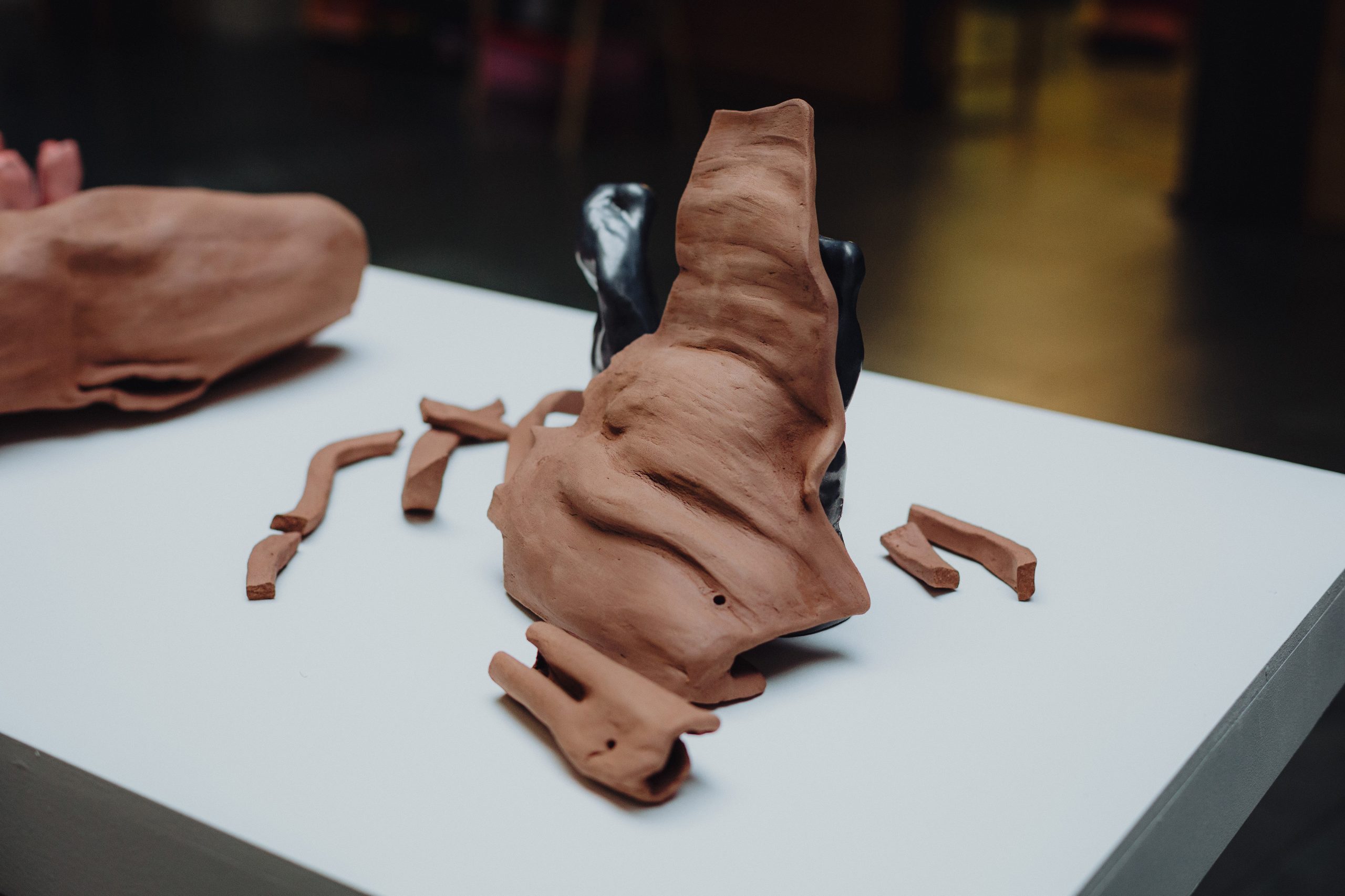

Titled: ‘warm & unflavoured / each morning’

Ritu’s practice is radical in its refusal to fix form and in embracing fluidity and transformation. There is no one style or signature silhouette. Her work morphs with instinct. “Mostly it’s with clay, because I thoroughly enjoy its haptic making process. Sometimes it’s metal, because I need to get the structure right.” Her studio is full of these fragments. Parts that don’t fit neatly into sculptural traditions, but pulse with meaning anyway. Medical tubing. Welding marks. Shapes that resemble bodies but never quite declare themselves. “I don’t plan the form. And when the material pushes back, we find a middle ground, together.”

Even within this improvisational approach to making, there is still attention to detail. There is intention. The hand sculpture, for instance, was cast not just for accuracy, but for its emotional weight. “I was trying to make something that held,” she says. “Held what it had been through. The softness didn’t work. I needed more tension.”

We then talk about reactions. How people respond to wounds, to marks, to anything that doesn’t conform to ideas of wellness or propriety. Her work doesn’t ask to be explained. But it invites you to stay with it longer than you might expect. I think that’s where the discomfort lies. Not in the imagery itself, but in how closely it resembles something you’ve felt but never articulated.

(L-R) Titled: ‘oh, cheer up, hen, will ye?!01; ‘oh, cheer up, hen, will ye?!02

She tells me about bartending in Glasgow, about being one of the few brown women behind a bar; about being a brown woman; and about being a woman. The constant phrase: “Oh, cheer up, hen, will ye?!” became the title for a recent sculptural series. “It’s always women who get told to smile,” she says. “Even if you’re barely holding it together.” That irritation found form in a twisted, spiked metal structure that seems to brace itself against visibility.

It’s many — legged, with one of them deliberately longer and more awkward. “At first, I added it for stability,” she says. “But then it felt like something else. Like this warning to stay away. Or that sense of being off — balance, emotionally and socially.” The lumbering limb becomes a metaphor for discomfort, for armour, for the kind of strangeness you build around yourself when people expect you to be pleasant. There’s also medical tubing embedded in the structure. A cannula, embodying the usual anxiety and a recent asthma episode during the making of this sculpture. It loops into and out of the form, unassuming and intrusive at once. “Sometimes I think the pieces are sick bodies,” she says. “Other times, they feel like monsters. They’re holding their space, finally.”

It’s this ambiguity I keep returning to. Her sculptures remain difficult to categorise. They don’t offer statements. They don’t need to. They hover in that space between familiarity and unease, between empathy and resistance.

When I ask her if she ever struggles to explain her work, she doesn’t hesitate. “Always,” she says. “I didn’t speak about the personal side of it for a long time. I’d say, ‘when people feel like this,’ never ‘when I felt like this.’” She credits one particular conversation with one of her tutors (during her MFA programme at The Glasgow School of Art) for making it easier for her. It made her think of the Middle-Class Shame, and the idea that if you talk about your pain, you’re clamouring for attention, and how it still lives in her. But she’s learning. To speak, to sculpt, and to occupy her rightful space. “Now I can say, yes, some of it comes from what I’ve been through. That doesn’t mean it’s only about me.”

What fascinates me about Ritu’s work is that it resists resolution. Nothing is neatly finished. Everything is shifting. Even in the smoothness of her newer pieces, there is something unruly beneath the surface. A twitch. A bruise. A refusal.

Towards the end of our call, we discussed failure. She tells me a story about a sculpture that exploded in the kiln recently, and how she kept one of its legs that survived. It looks like a hoof. “It’s ridiculous, but I do that rather often – keep the broken bits,” she laughs. “But they have to be relic-ed, it feels like a necessary rite, it feels true.”

That’s how most of her work feels to me. Not complete or crafted, but true. True to a moment, to a discomfort, to a body trying to speak. There is something brave in that. Not heroic, but brave in a quieter, more radical way. The kind of bravery that doesn’t need to be declared — only witnessed.

And so I did. I looked. And it looked back.

Artist Website: www.ritu-arya.com

Artist Instagram: www.instagram.com/ritu.arya

Words by Niyati Hirani.

Feature Image ‘warm & unflavoured / each morning’ by Ritu Arya.