“Sri Lanka’s Debt Crisis Is So Bad The Government Doesn’t Even Know How Much Money It Owes” was the title of a Forbes article in 2016. The intentions of the government seemed noble – increase the economic potential of the island nation by bringing more foreign money into its economy. But power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

It’s like solving a mathematical equation. If you approach solving a problem with a series of badly judged events, there’s very little to be done to fix the result. Sri Lanka’s fall is an example of that.

Once known as “Serendip” – also the root word for serendipity – the fall of the Lankan glory now lays open for the world to see. This pattern of change is almost a common phenomenon, and it seems like the most beautiful of places witness their downfall first – Kashmir (India), Syria, Afghanistan (amongst many others) — and now Sri Lanka. These events are not very different from each other, they almost seem like harbingers of doom that is taking over the way countries are now living their realities.

Although this piece centres around the crisis in Sri Lanka, this is a problem of the world, and thus important for us to stop, and understand. Because globalisation is rooted in the fact that the world is one big global village where countries look after each other to survive. Just like a colony of trees in a forest acts as a single unit, protecting each other and helping the jungle survive, so can the countries of the world. But unfortunately, the economic tear down of the Lankan life is telling another story — bursting the bubble of a global village; and the world is witnessing a mega and slowed-down version of the Jenga blocks falling.

There is little need to expound at length on the economic, social, and daily pain that the people of Sri Lanka are experiencing – an unprecedented, and almost unbelievable shortage of the most basic goods and services like paper, fuel, electricity, to start the list. But we, as spectators have two options the lie ahead of us. One can draw on the misery, look with shock, and move on. But to introspect on the series of events is to realise that there’s a pattern that’s taking over the way our world operates. The one takeaway that seems central to the event is this –

The majoritarian ethnoreligious nationalism comes with limits that cannot be pushed, and a diasporic chase of that sentiment cannot sustain the long-term growth of a nation and its people.”

It was Jeff Kingston who said, “A majority driven sentiment drives the governance of the Asian politicals and the world seems to only take advantage of that. Sri Lanka is a monumental example telling us that there is a limit to economic pain and bad governance that a country will tolerate before it starts to break.”

An academic discourse will emerge from these events, and we’ll know a lot more about the undercurrents of this situation. But at its core, the fall of the Lankan glory is an age-old story of opportunism. And events of this magnitude don’t crop out of no where, and such downfalls don’t come from the power of one.

Prelude to the Fiasco:

Foundations of a political and economic fiasco were laid long ago in Sri Lanka, with strains of irreversible damage to be seen a decade ago when its GDP spiralled downward in the start of 2012. In 2016, the European Union stepped in to help, allowing the island nation to export products, including its top export garments, tax-free to the EU.

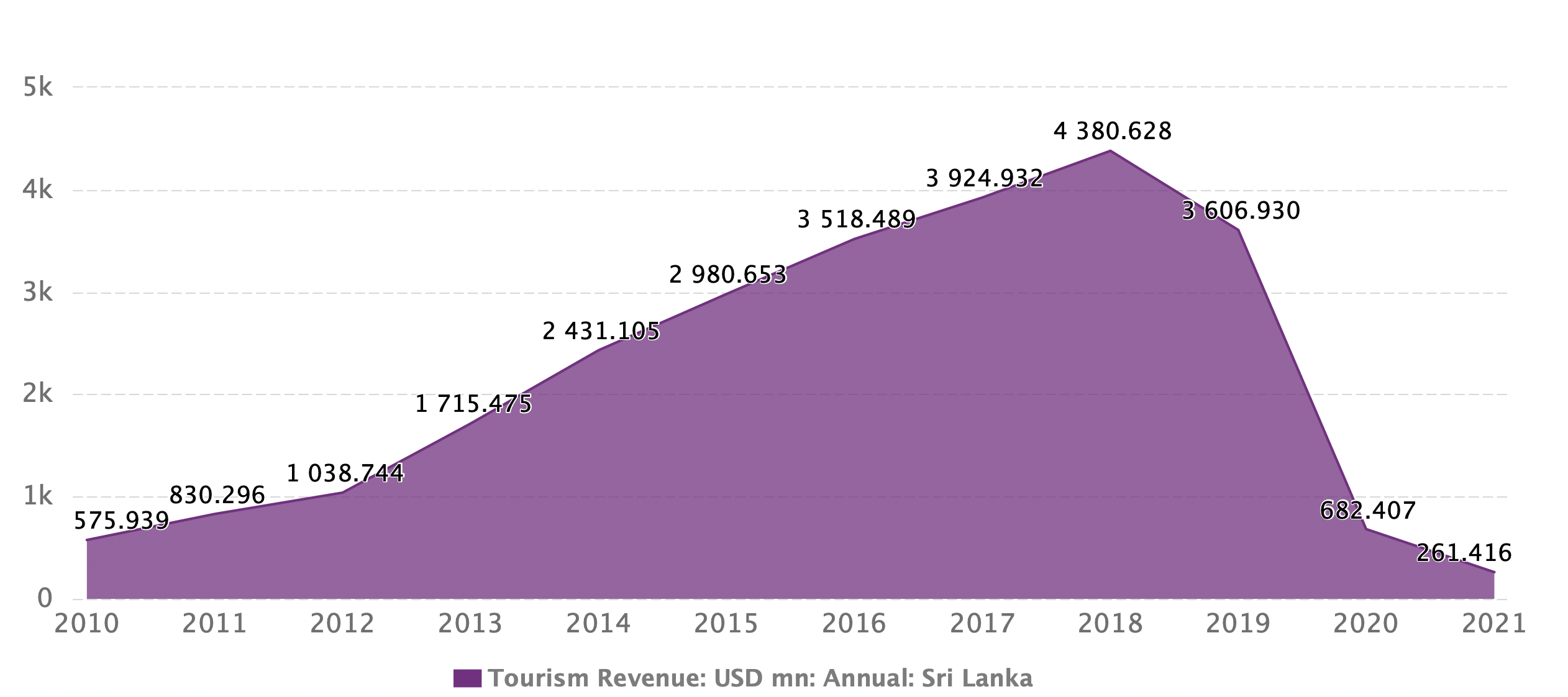

It looked like the beginning of a silver lining; but in 2017, the Financial Action Task Force on money laundering and terrorist financing listed Sri Lanka as non-compliant. These harbingers of doom heightened in 2019. First, the Colombo bombings meant that tourism, which makes up 10 per cent of Sri Lanka’s economy, was to shrivel. Then came the elections. Gotbaya Rajpaksh became the prime minister once again, dissolved the legislature, and filled the government with his own relatives and cronies.

While Sri Lanka was running on trade deficit for decades, the shortsightedness of the Rajapaksha government along with massive money laundering, meant while loans from around the world were coming into the Lankan economy to help it recover, the deficit only widened.

Another dent in the fiasco came with the Russia-Ukraine war. One of the strategies Sri Lanka had adopted was to export tea – a locally abundant plantation valued like a luxurious delicacy in the world – to pay off its mounting debts. But with Russia and Ukraine being Sri Lanka’s biggest tea importers, the war left the nation on another economic dead-end.

To not speak of China when talking about Sri Lanka’s downfall, would be to only give a two-dimensional side of things. China was gaining a lot of international attention for draining the Lankan economy dry, with uncountable amounts of loans sanctioned to the nation, along with the infamous trade-free international port in the making. But it will be a limited perspective to absorb, if we ignored how China could be held accountable for what happened in 2022. Stakeholders like China, are opportunist gainers, if nothing else, in the economic depression that now looms over Sri Lanka.

There are many things to be said, and assumptions to be made about what exactly it was that caused Sri Lanka to sink so deeply in debt in 2022. But that inquiry is a complex one and will unfold further as time passes, and more intelligence is revealed to the world. But as op-ed sections of popular publications fill in with financial numbers, GDP graphs, and singular lines of finding who is to blame for Sri Lanka’s situation, we’re somehow distracted by the sheer misery that the people of the nation are going through. Because while tracing the genealogy of a historic event like this is important, it doesn’t end here. A lesson we, as a global village, need to learn from Sri Lanka is that in times of an imminent crisis, people have a lot to say, but very few come to offer real help.

That alone, should motivate nations around Sri Lanka to listen, look within themselves, and re-evaluate the direction we’re headed towards as a collective of countries trying to save ourselves from similar plummets in the mouths of economic blackholes.

What global neighbours can learn:

There seems to be a pattern to how Sri Lankan rules approach a national problem. Their solutions are rooted in creating damage, borrowing money to fix it, and misusing that loan to create further financial trenches for its people. It shows in a number of things it does. And there are three major takeaways that countries can immediately learn from Sri Lanka’s current situation:

1.Borrowing money without foresight is not a solution to a tumbling economy

A crisis management approach that relies on borrowing more money to fix a debt doesn’t work, especially if the borrowed money is being spent on experimental and unproductive projects with no guarantee of success. While borrowing more money in itself is not the final ingredient in the recipe for a disaster, a populist approach to spending that money is. When the governments don’t feel the need to be transparent about their monetary investments, more often than not it results from an underlying wish to fund their own personal pockets.

Even after the debt trap that Sri Lanka finds itself in today, its plan of action depends on borrowing more money from its sister countries including China, India, and even Bangladesh. The world is hesitant to offer help because what the decision-makers fail to prove, yet again, is how well is the money going to be utilised. The law remains simple – you like investing in a market that shows a promise to grow. But a country that seems to have no particular vision for how it’s going to recover, means it’s going to face the threat of being stranded.

We live in times of extreme political upheavals; a time where political decisions can cause more economic harm than the world wars of the 40s ever could. And so the political war is unseen but looms everywhere like ether. And rightly so, countries don’t want to extend monetary help to a widening black hole. What we, as spectators of such a catastrophe need to learn, is that countries need to start thinking of new ways to safe proof themselves against economic calamities like these. Watching the Lankan economy shrivel shouldn’t make us feel safer that it didn’t happen to us, but prepare us better for what can happen in the future.

2. A development funded by the outsider means the outsider owns many pieces of the cake

A naive spectator of Sri Lanka’s case is tempted to come to the conclusion that the country shouldn’t have borrowed all the money it did from China. The reasoning seems rather justified if you look at the numbers – China alone accounts for around 10 per cent of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt, which comes close to about $8 billion. This follows years of diplomats talking openly about the predatory nature of China’s loan lending schemes across the world.

And this is where the tale of opportunist stakeholders becomes clear. Developing nations like Sri Lanka look towards countries like China for loans, because western institutions are infamous for levying stringent conditions for money lending processes. China was quick to realise there was an opportunity – nations like Sri Lanka need the money. Western countries won’t give it to them so easily. So China came in to fill the gap and make loan taking easy.

While the blame for inappropriate allocation and short-sightedness in regards to these loans rests within the rules of Sri Lanka, there was very little to do but to take this money. This pattern is emerging across the globe. In February 2022, Pakistan owed $18.4 billion of its external debt to China. With recent political developments that are going to follow the ousting of Imran Khan-led the Pakistani government, it seems like Pakistan is already following the footsteps of Sri Lanka.

It’s time for South Asian countries to look inwards and work towards creating stronger regional associations. Because the situation remains the same – developing nations often need financial help to grow (just like a growing business), but the West is not going to make borrowing money any easier. China is going to be standing right at our doors, offering easy money. But it also means any money taken from China, is to allow it to have a significant political say in our economies. In simpler words – an external player has no motivation to offer us sustainable solutions unless they can benefit from it significantly. This is where a stronger regional corporation amongst the South East Asian countries holds the potential to break this pattern.

3.The Neo Green Revolution cannot be a quick fix for a failing economy

The cherry on top of a series of bad decisions happened when in 2019, the Rajapaksha government promised to implement a nationwide campaign, aiming to help the country’s farmers turn 100 per cent organic in their practices. It doesn’t sound like an accidental coincidence that at the same time, it signed a major export order of fertilisers with China. The plan, at least to the government, looked very efficient – discard the fertilisers, sell them to China to bring in some money, and meanwhile, create self-reliance for the farmers by forcing 2 million farmers to go organic.

Just another major policy with no statistical backing that guarantees success, the nationwide experiment was soon abandoned, but not before creating irreversible damage to the already dwindling economy.

One of the first areas to take a hit was a drop in its tea production, which was unaffordable for Sri Lanka since it was its primary source of income for recovering from its foreign debt. To establish context, and understand the brevity of this setback, we need to realise that for centuries Sri Lanka was known for being the world’s foremost producer of tea, especially when it came to its quality. In 2013, for example, Sri Lanka was the world’s largest tea exporter and the fourth largest tea producer. Export earnings were nearing a total of US $1.5 billion.

Women harvesting in the Tea Plantation.

This was the beginning of Sri Lanka losing whatever little self-reliance it had its way. A country that had taken pride in its long self-sufficient production of rice, is now forced to import $450 million worth of rice. Meanwhile, inflation got worse and domestic prices of rice shot up by about 50 per cent.

And this sent the government back to the same loop that never really worked, but somehow remained as the go-to strategy for every disaster it was creating for itself. The government started to offer $200 million to farmers as direct compensation, and an additional $149 million in price subsidies to rice farmers who suffered losses. And so to fix the damage that they created themselves, the government turned to the world again asking for monetary help. The rulers, amidst this self-made fiasco, started importing rice using credit lines from friendly neighbours.

Writer’s two cents:

In times like ours, where international conflicts rise fast, but inflation faster, the Lankan crisis leaves the spared spectators with a lot to ponder upon. While the three lessons above are complex ideas for countries to implement with a click of hands, a resilient, due course can help them better with situations like the Sri Lankan crisis, if not prevent one.

Words by Avantika Mishra

Photographs via Pexels and CEIC Data

Cover Image via Finshots