“No matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed his subject, the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search such a picture for the tiny spark of contingency, of the here and now, with which reality has (so to speak) seared the subject, to find the inconspicuous spot where in the immediacy of that long-forgotten moment the future nests so eloquently that we, looking back, may rediscover it.” – Walter Benjamin, ‘A Little History of Photography’

I believe if it wasn’t for photographs, we wouldn’t be able to understand the remnants of our colonised past to the extent we currently do. Stories passed down by history textbooks and ancestors only go so far and would be slightly redundant if there weren’t any visuals to aid the narrative.

The British were faced with a cultural dichotomy when they colonised our shores. Photography helped them unravel the contrast, document what they found fascinating and leave an imprint on the history of photography.

‘Bourne and Shepherd’ was born in 1863 amidst this period of cultural fascination and surge of British photographers. Helmed by two prominent British photographers- Samuel Bourne and Charles Shepherd; both widely renowned for their photographic documentation of their years in India. They went on to form what would be known as one of the oldest, established photographic businesses in the world. The firm were commercial publishers of landscape and topographical views of India. Primarily based in Kolkata and Shimla, where they operated their famous portrait studios, their work was widely sold across the Indian subcontinent by agents and in Britain by wholesale distributors.

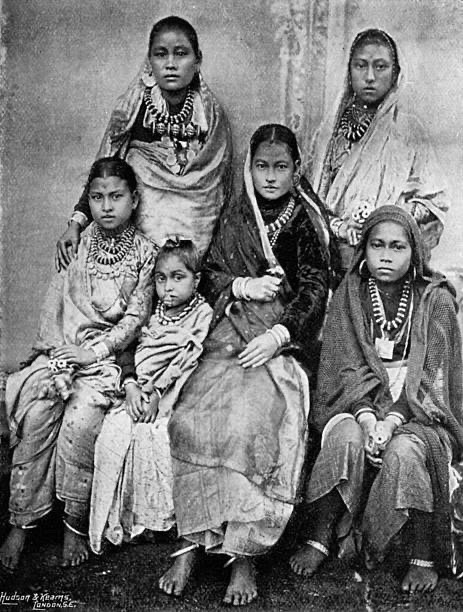

(1) The Supreme Indian Council, Simla, 1864, Bourne and Shepherd.

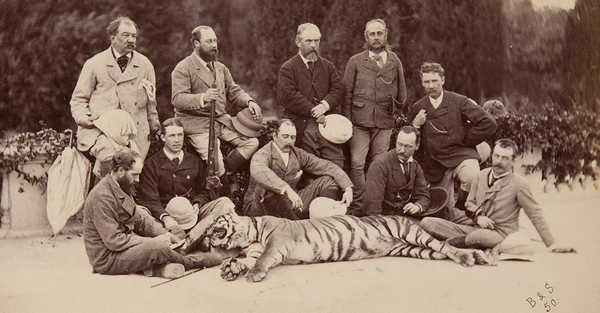

(2) H.E. The Viceroy’s Elephant; 1863 Bourne & Shepherd.

Samuel Bourne is known for his work in India in the years 1863-70. In the duration of these 7 years Bourne managed to capture 2,200 images of the landscape and architecture of India and the Himalayas. He travelled through India extensively, capturing many versatile facets of Indian culture, heritage and landscape in the lens of his beloved 10×12 inch plate camera. His expansive, impressive body of work paid great attention to technical perfection and this is why his work was regarded by most as artistic excellence. He wasn’t keen on capturing opulence or stability. His photography was aimed towards understanding the various landscapes in India and how it intersected with the various cultures in place at the said region. His ability to create insightful photographs whilst travelling in the remotest areas of the Himalayas whilst working under strenuous physical conditions was what led him to be one of the most renowned British photographers of the 19th century.

The Manirung Pass, 1860s, Samuel Bourne

Afridis at Jamrud Fort, 1866 Charles Shepherd

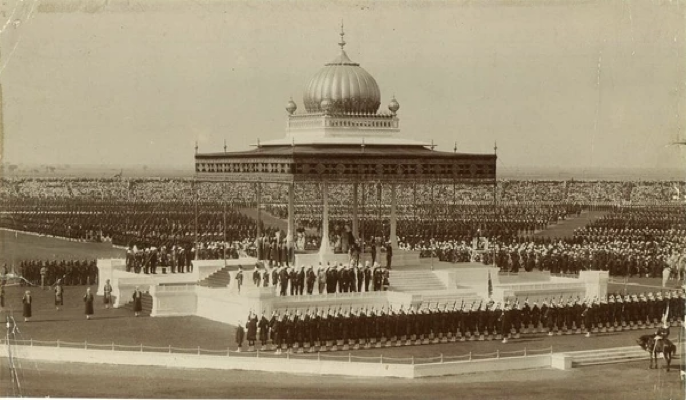

‘Bourne and Shepherd’ went on to become one of the most successful commercial photo studios in 19th and early 20th century India, with agencies spanning all over India and foreign extensions in London and Paris. Their clients were usually from the upper echelons of society such as the Viceroy of India, Indian Maharajas and Maharanis, and British Lords and Ladies. Bourne and Shepherd’s popularity increased among aristocrats and royalty as they became renowned for their flawless portraits. The studio was famously commissioned to take photographs of the Delhi Durbar when King George V visited India. They were rewarded and recognised for their work as they became recipients of the ‘Kaisar-i-Hind’ medal.

King George V and Queen Mary seated upon the dais, Delhi Durbar,

1911, Bourne and Shepherd

Their studio in Kolkata would go on to run for an astonishing 176 years until its unfortunate end on 20th April, 2016. The studio had survived through various streams of political and social turbulence, multiple owners but in the end succumbed to the fact that the age of digital photography had taken over. In 1991, a fire burnt through the majority of Bourne and Shepherd’s archives, a devastating mishap from which the studio never recovered. The onset of the 21st century brought with it the bane and blessing of digital photography. Smartphones and social media followed shortly after and film photography went out in a silent yet dignified manner. The skilled craft of studio photography, the sentimentality of black-and-white prints and colour portrait prints developed intricately and arduously by experienced studio personnel, could simply not combat with the combined force of the newborn digital, internet led world.

Bourne and Shepherd Studio Kolkata, 2009, Roshan Rao

Bourne and Shepherd’s contribution to the documentation of colonised India via photographs at the time may not have been seen as monumental then as it is now. These photographs help us understand what would now be regarded as a “parallel universe”. The fascination to document this cultural shock most British photographers went through has resulted in a very rich archive of photos highlighting and shedding light on various parts of the empire. It allows us to understand our milieu of an era gone by in a comprehensive manner, that simply wouldn’t have been possible if it weren’t for this plethora of visuals. For example, Bourne & Shepherd’s collection was a key reference point for Satyajit Ray’s film ‘Shatranj Ke Khiladi’. It is said that Ray came to see the collection of photographs in order to understand the culture and ambience of a time not known to him and it helped him visualise the costumes for the film. The photographic documentation of our past allows us access to the perspectives of multiple individuals, access that we were denied for 300 years. We can’t wind back the clock but the medium of photography allows us to curate, preserve moments that will someday, hopefully, enrich our present and future.

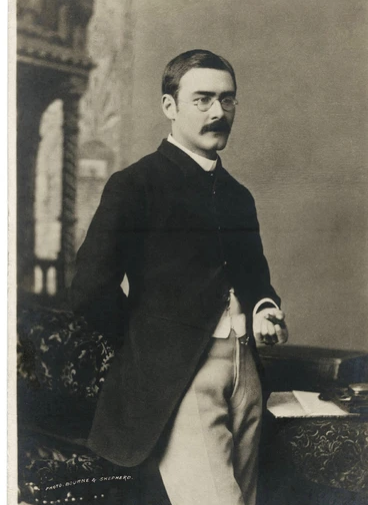

1: Mary Victoria (née Leiter), Lady Curzon of Keddleston 1902, 2: Rudyard Kipling 1892, 3: Maharaja Sajjan Singh of Udaipur, 1877.

Text by Anithya Balachandran