Millennia ago, the very first homo sapiens asserted their existence through handprints on cave walls, followed by elaborate hunting scenes, created using dyes and pigments found in nature. Forevermore, humans have attempted to immortalise their life in artwork that tells stories; stories of an ancient time, stories of strife and perseverance, stories of ingenuity and creativity. Art has been the simplest form of expression that has come naturally to humans since the beginning of time.

India is home to a plethora of folk art, an integral aspect that helps preserve the country’s rich cultural heritage. Communities across India practice folk art in unique forms, including tribal art and village crafts. These traditional modes of art employ distinctive elements and mediums, using textiles, rock painting, wall painting, sculpting, and carving to bring their stories to life. These art forms that are thousands of years old capture the diversity of beliefs, cultural and religious practices, and the way of life of people hailing from different parts of the country. However, these meticulously created art forms are slowly being washed away by the sea of time. As the years go by, the kalakaars, craftsmen trained in their fields, struggle to resuscitate the dying arts of the past.

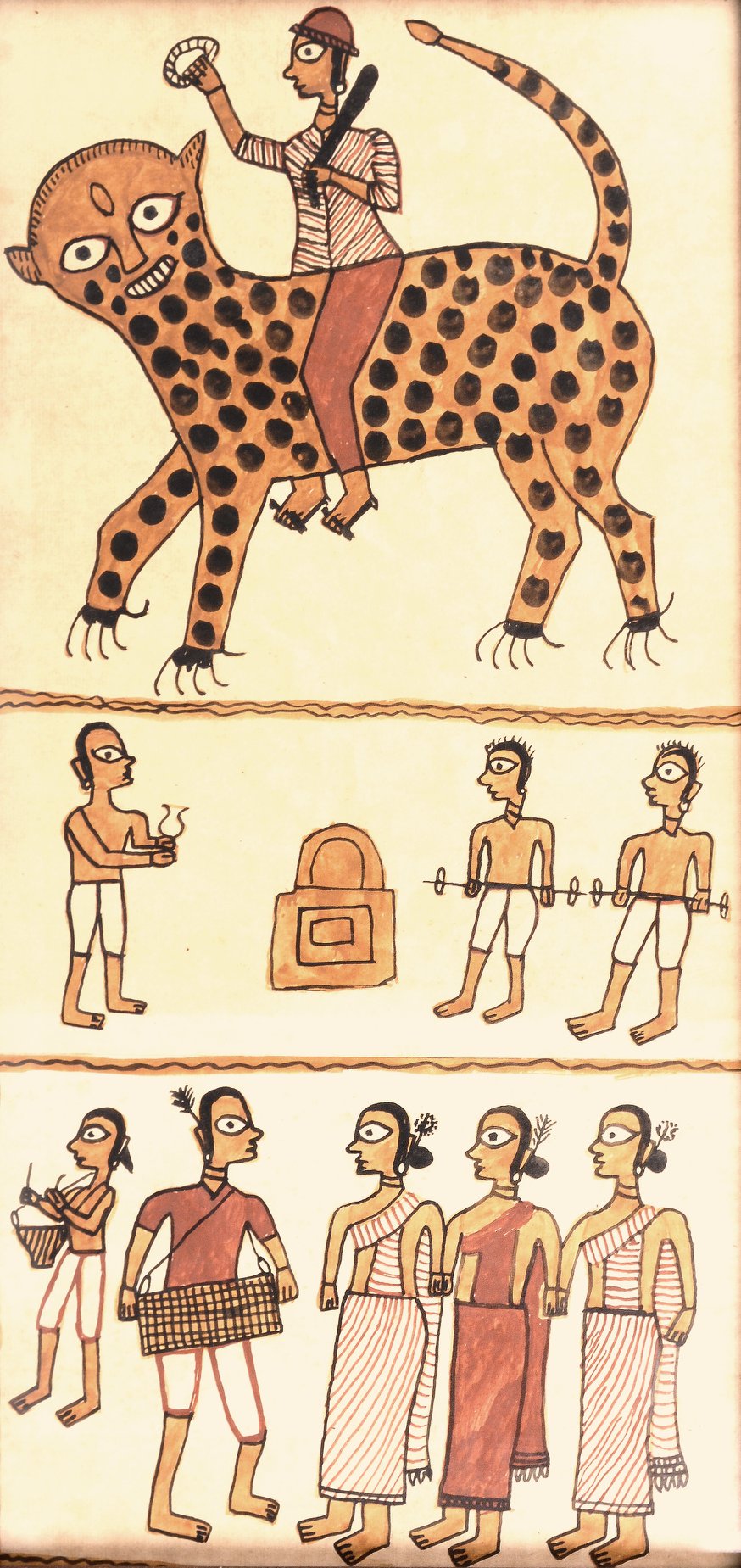

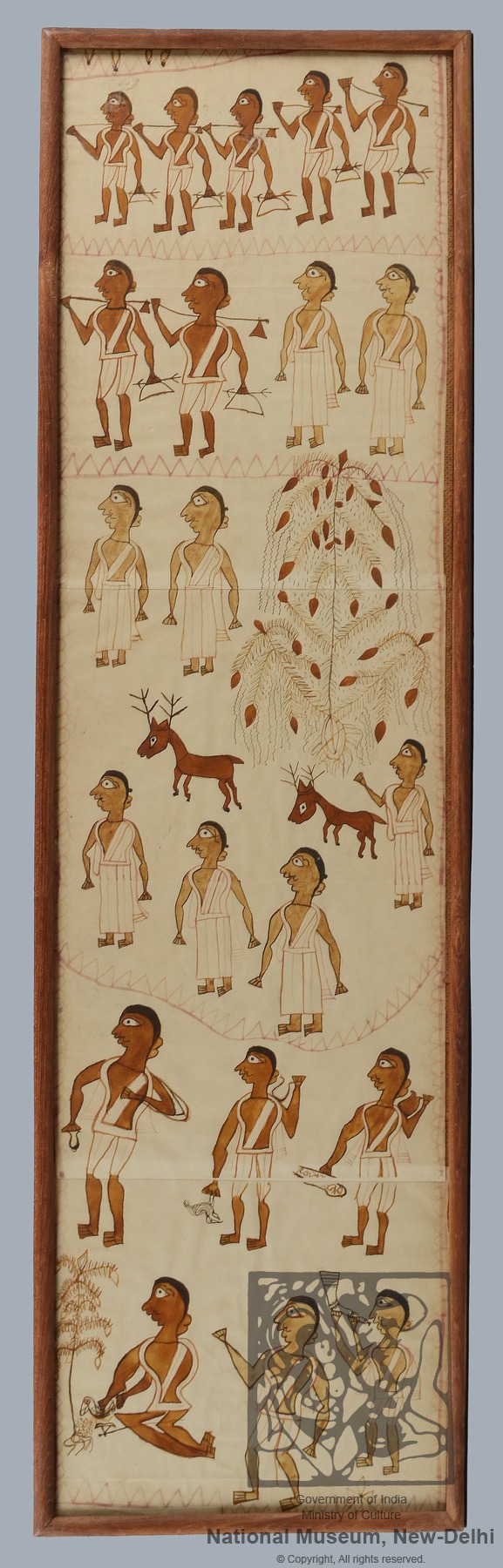

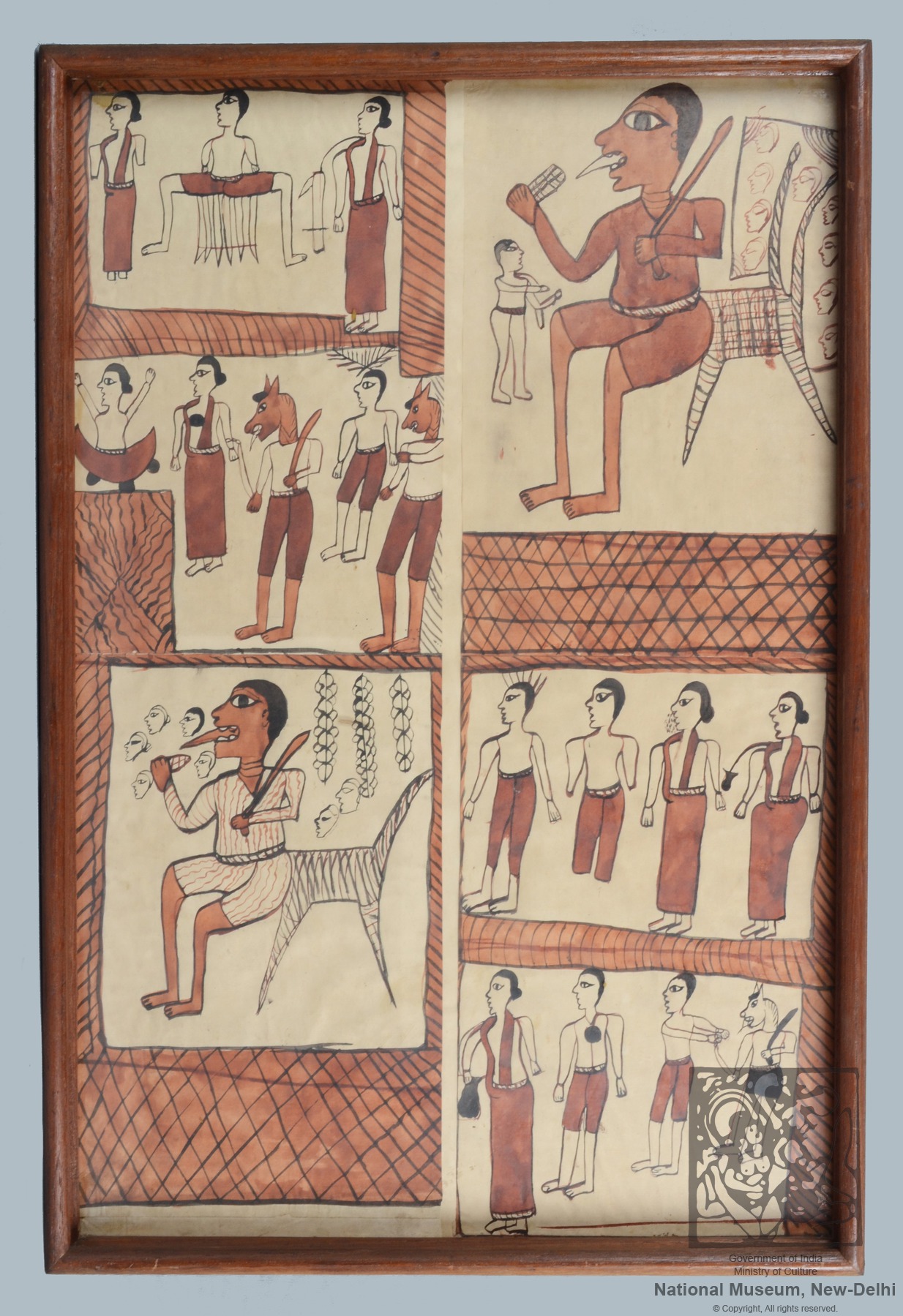

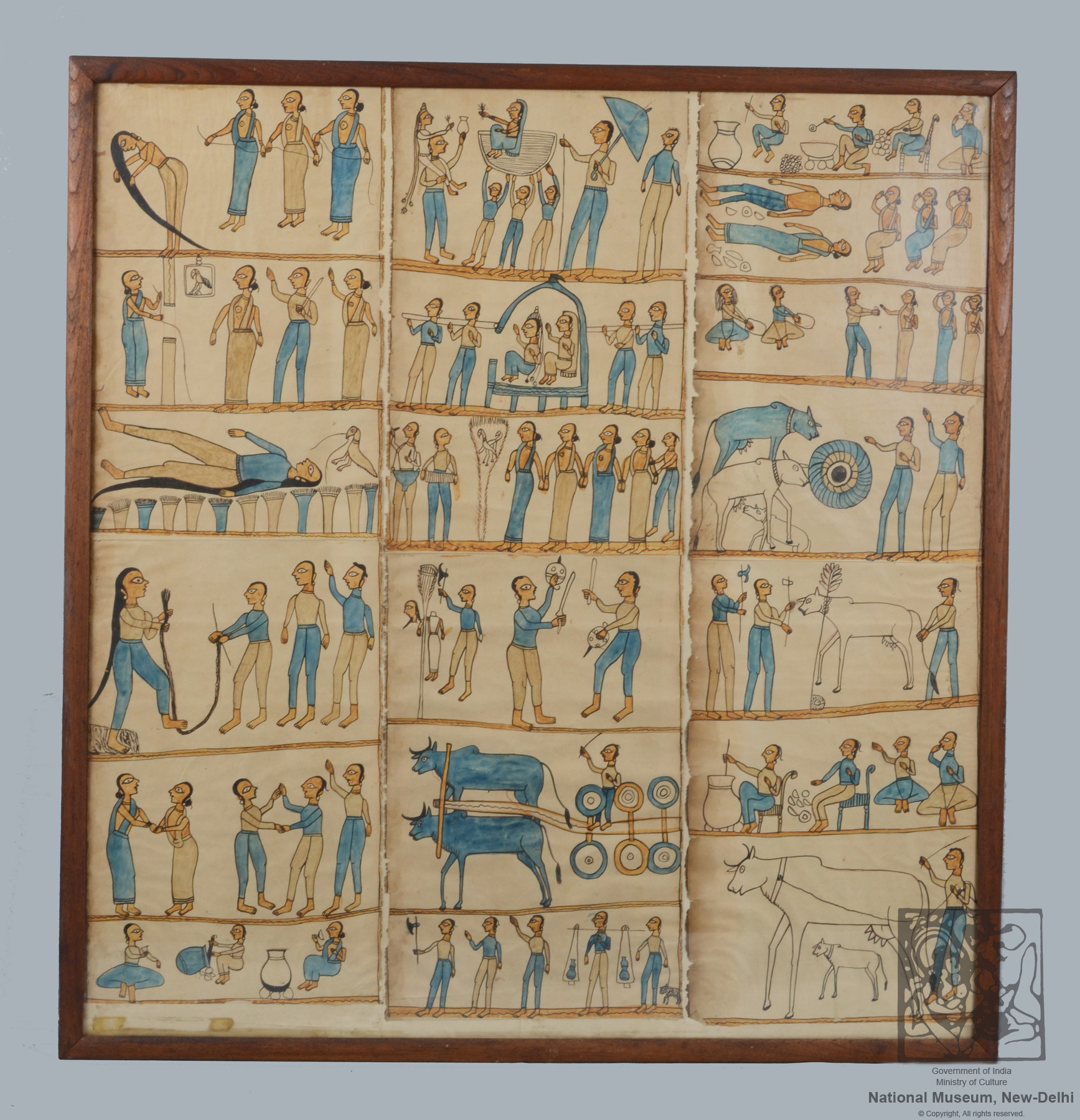

Nestled in Jharkhand, the land of forests, is the Dumka district, the sacred home of Jadopatia. A way of telling stories about the origins of life, Hindu mythology, tribal life, rituals, and festivals, the art form of Jadopatia bears a very fascinating history. It is believed that the term Jadopatia has roots in the words jado, meaning magic, and patia, that is scroll-painter. Some sources also claim that the Santhal word for artist is jado, whence the name arises. This unique art form comprises paintings made using natural pigments from stones, leaves, flowers, and tree bark, upon a scroll of varying length. They can be traced back to neighbouring West Bengal from over 2000 years ago, from which the chitrakars (picture makers) originated. The Jadopatias are male performers who hail from West Bengal, and the borders of Bihar, Jharkhand, and Orissa. The profession of these bards involves travelling from hamlet to hamlet, performing the creation myth with songs and stories as depicted in their scrolls, in exchange for an offering of rice.

There is an interesting creation story about the chitrakars of the Santhal tribe, which inserts them deep into the cultural fabric of the people. According to the legend, the first man and woman were Pilchu Haram and Pilchu Budhi. They were inconsolable upon the demise of their oldest son. The tribal god Marang Buru created the first chitrakar from the dirt on his forehead, and thus gave the chitrakar his duty: he was to approach the couple and paint a chitra, in illustration, of their deceased son, and receive a dan, or an offering, in return for his services.

This particular folktale sheds light on the work undertaken by the jadopatia chitrakars as funeral priests of sorts, who partake in a mortuary ritual called cokhodan, which translates to ‘the gift of the eye’. In this elaborate ritual, the revered chitrakar is called when a death occurs in a family, and is given the responsibility of aiding the deceased in their journey to heaven. The deceased individual is painted upon a scroll using a special goat-hair brush, with the eyes of the painting being left incomplete. The chitrakar then recites some incantations and paints in the eyes once he has been remunerated, thus symbolically giving the deceased the gift of sight to help them navigate in the afterlife.

As we enter the 20th century, it becomes hard for traditions such as these to maintain relevance in a world that is rapidly urbanising. The chitrakars do not have the opportunity to have elaborate performances surrounding their beautifully painted scrolls; today, they are limited to simply painting the scenes and selling their work in order to make a living. Many chitrakars are left with no choice but to leave this profession and take up manual labour, which is more financially viable. Unfortunately, there is not much information about this practice, and it has fallen prey to fast-paced industrialisation. The story of the Jadopatias is truly one that should not be forgotten, given that the phenomenal skill and artistry of these magic painters of Jharkhand has immortalised countless people and tales of the past.

Words by Gayatri Thakkar.

Jadopatia paintings and scroll via National Museum, New Delhi.