In 2013, when 23-year-old photographer, Siddharth Behl got to the remote Changthang plateau in Ladakh the mood in the local village was tense and sombre. A few weeks prior the region had been inundated with unusually heavy snowfall and the villagers had lost over 20,000 livestock. “Along with the pressures of the intense cold there was a heaviness in the air. The temperature has dropped a further 20 degrees than what is normal for that time of the year. The goats had died from the bitter cold and starvation,” says Behl.

Nestled between the lofty Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges the arid Changthang plateau is home to the hardy Changpa tribe. Nomadic pastoralists, the Changpas traverse the region with their herds of yak, sheep and goat looking for fresh pastures. Their prized Changra goats produce the world’s finest wool, pashmina – sought after for both its warmth and lightness. Barely 12 microns in width and almost eight times lighter than human hair, the delicate strands may seem like air but when woven into thread and used to make shawls, the warmth of a pure pashmina is incomparable.

The lofty Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges that surround the arid Changthang plateau.

Elders of the Changpa Tribe.

Changpas are buddhist believers, they do not let any part of a deceased animal go to waste – horns are used to ward off wild animals, the meat as food and the skin as a protective cover against the wind.

At an altitude of over 15,000 feet above sea level, both humans and animals have adapted to the harsh desert landscape and gruelling weather conditions that prevail there. In winters, temperatures can drop to minus 40 degrees centigrade. To survive the bitter cold the Changra goats grow a warm but soft undercoat. During the annual moulting season in spring. The fibres are collected by combing. Once collected, the hairs are cleaned, sifted and then spun into thread.

While men set out to graze and tend the flock, the women of the household take care of spinning and weaving delicate pashminas. The customs and traditions of Changpas are deeply interwoven with the land and their herd.

Although prone to inhospitable weather, the winter of 2013 was brutal and sadly, the Changpas knew that this was just the beginning. In this far flung remote corner of the Himalayas, effects of climate change are felt keenly. Summers are getting drier and winters warmer, both of which adversely affect the vegetation that the goats depend on. Over the years, these climatic variations have also led to changes in the undergrowth of the goats which in turn affects the quality of wool that’s produced.

A Changpa shepherdess spins pashmina yarn while another grazes the prized herd of Changra goats.

Changpa men tend and graze the flock.

Having witnessed the aftermath of the disaster in 2013, Behl went back to the region twice over the following decade to document the harsh realities of living in Changthang and the mounting challenges the local tribes face in order to carry out a profession that’s been part of their families for over generations. Faced with uncertain climatic conditions, hardships and other competitive pressures such as cheaper imports of wool from China; the younger generations are leaving behind this nomadic life and choosing instead to move to nearby cities. Parents are also torn between educating their children or teaching them to carry on their traditional way of life. As more and more members of the tribe migrate from Changthang there are fewer and fewer people left to produce pashmina.

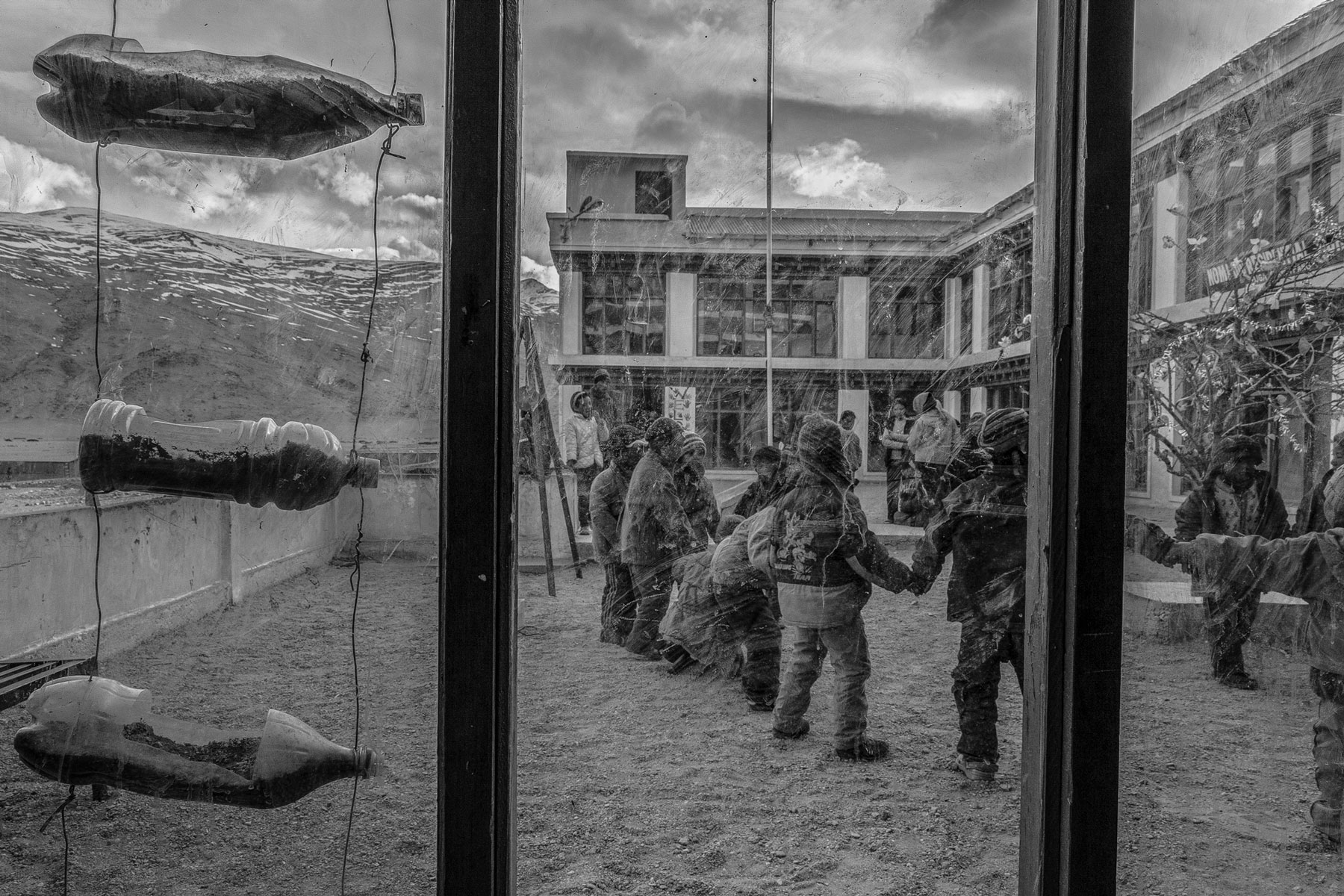

The Nomadic Residential School in Puga village. The school provides housing and education to over 120 children between the ages of three and eighteen.

Titled ‘The Silent Disaster’ Behl’s black and white photographs capture the intimate relationship between the tribe and their goats, and the precarious fate of the world’s finest wool.

Words by Chaitali Patel

Photographs by Siddharth Behl