“Age of Prison”, an absurdist digital play produced by Alfaaz Productions, curiously paints a Jackson Pollock-esque imagery of freedom of expression. Directed by Ankit Verma, starring himself and Rashmi Mann, the play begins with two prisoners in a dark room, with an omnipresent voice questioning and commanding them. Essentially, the work serves as a metaphor for the complexities surrounding freedom of expression, particularly in light of events during the pandemic. Artists and creatives faced scrutiny, legal actions, and censorship, often without valid grounds. The play explores the arbitrary nature of such oppression, symbolised by two individuals unjustly imprisoned, unaware of their supposed crimes.

Each chapter delves into different facets of their struggle, reflecting on themes like happiness and the pursuit of freedom. The play deliberately avoids a concrete interpretation, inviting audiences to bring their perspectives. Its conclusion, where one prisoner is electrocuted and roles switch, underscores the unpredictability and cyclic nature of oppression, suggesting that anyone could find themselves in similar circumstances. Through this, the playwright aims to highlight societal control’s pervasive and relentless nature and the potential for individuals to become ensnared in its grip.

For me, the dream sequence stands out prominently in the play, as its visual impact resonates strongly without the need for verbal explanation. Orchestrated by the jailer, it serves as a journey through a spectrum of emotions, transitioning from tranquil melodies to chaotic dissonance, interwoven with a plethora of conflicting thoughts and perspectives. Each shift in tone is accompanied by a corresponding alteration in colour, evolving from calming blues to the ominous hue of red, symbolising the influence of malevolence.

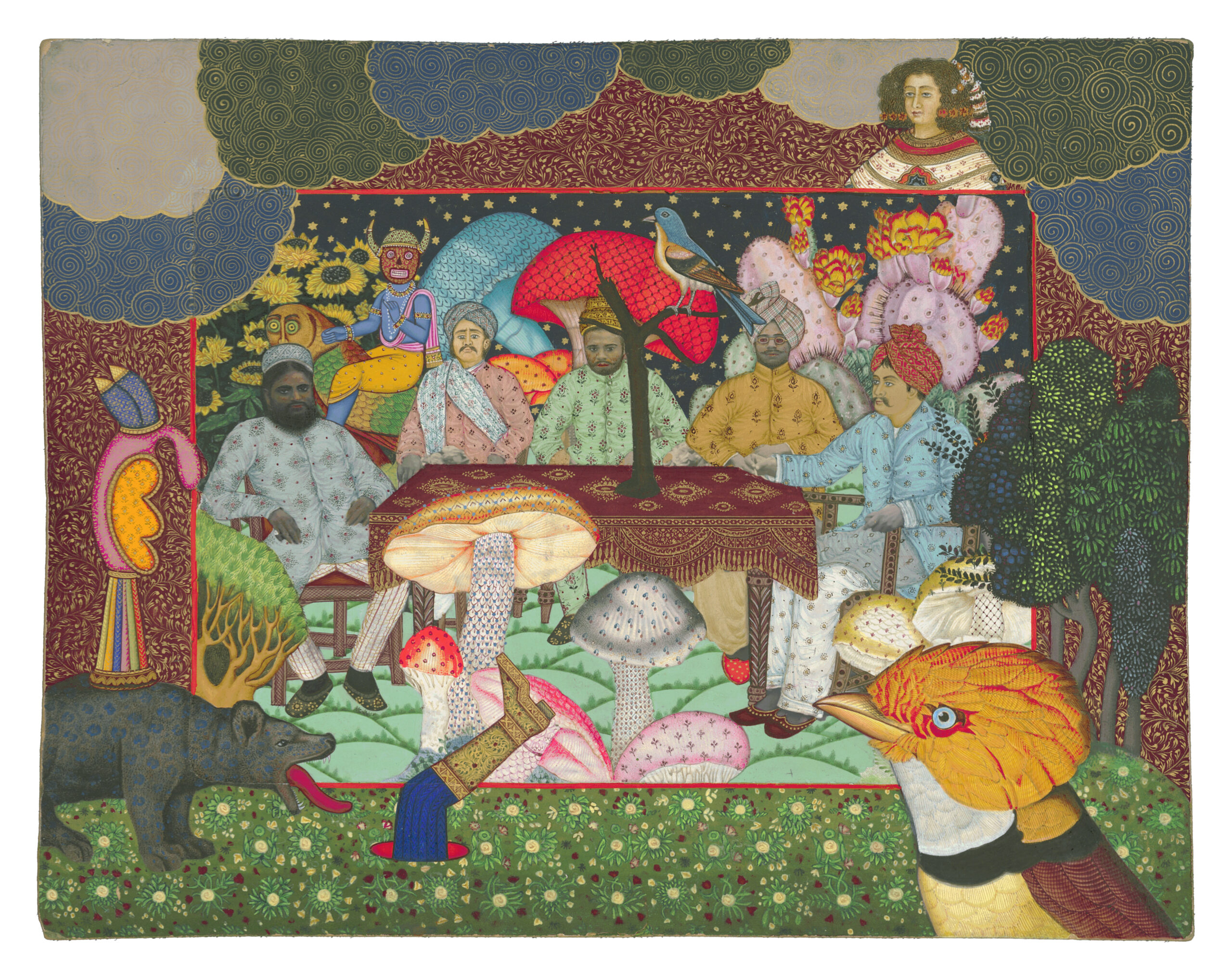

In frame: Ankit Verma and Rashmi Mann

In essence, the jailer manipulates the prisoners’ perceptions, moulding their worldview and emotions to his whim. This manipulation serves as a metaphor for the pervasive influence of authority figures, societal norms, and external forces, which shape individuals’ perceptions and feelings towards the world around them.

The sequence culminates in a moment where the prisoners are directed to sleep, an action presented as an imperative rather than a choice. In earlier iterations of the play, audiences were prompted to select between a dream or a nightmare, yet regardless of their choice, the outcome remained unchanged. This symbolic gesture underscores the idea that even in situations where individuals believe they possess agency or autonomy, they are ultimately subject to the control of higher powers or unseen forces.

The portrayal of claustrophobia within the play is masterfully executed through a combination of visual and auditory elements, evoking a palpable sense of confinement and unease in the audience. Firstly, the use of pinched frames creates a visual sensation of constriction, framing characters and scenes within tight, confined spaces. This deliberate framing choice serves to emphasise the physical limitations and suffocating nature of the environment, heightening the audience’s perception of claustrophobia.

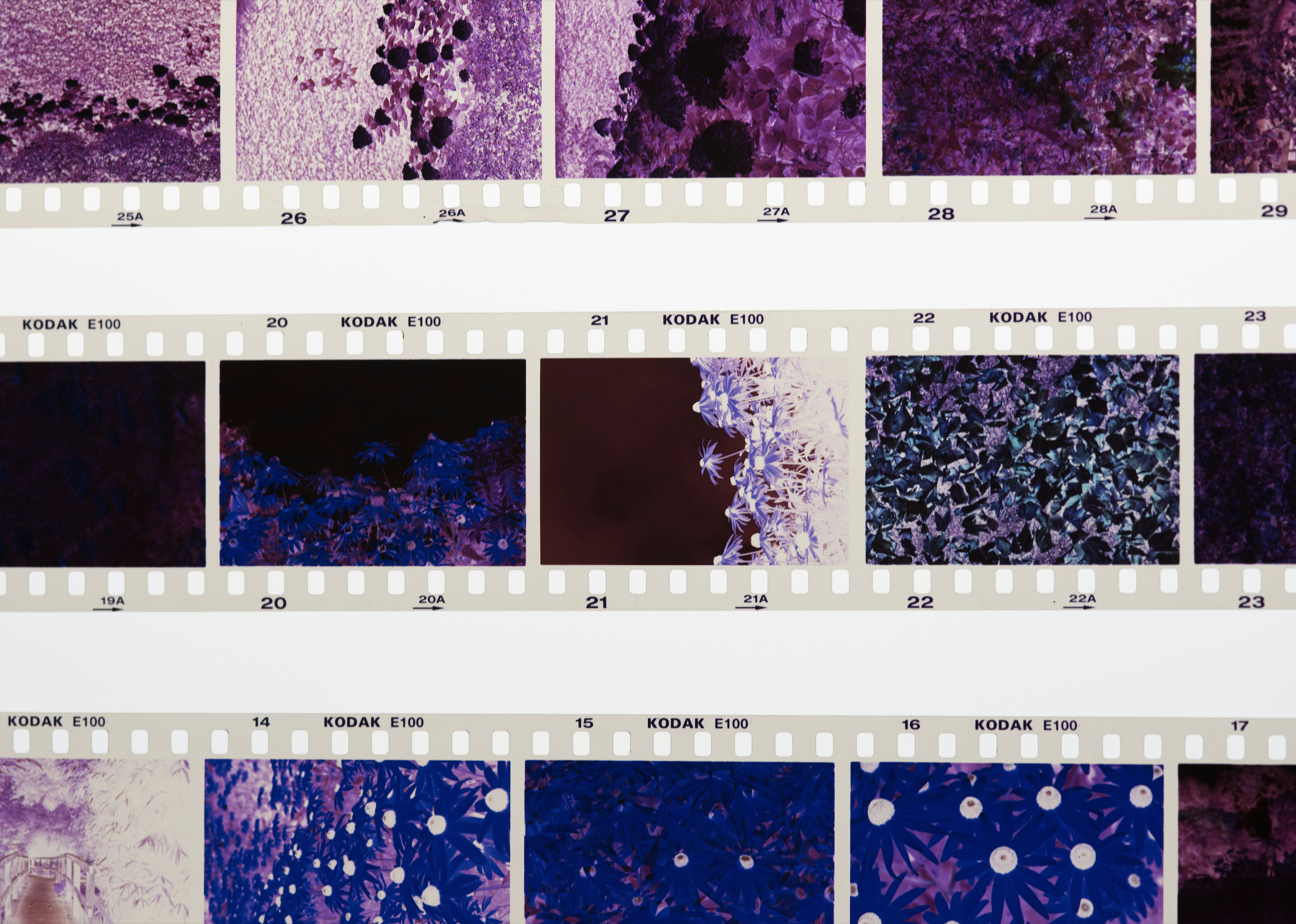

Stills from ‘The Age of Prison’

The creation of a dark atmosphere contributes to the sense of enclosure and isolation within the space. Dim lighting or shadows cast by obstructions further obscure the surroundings, intensifying the feeling of being trapped within a confined area. In addition to visual cues, the play employs sounds echoing within the space to enhance the perception of smallness. This auditory effect amplifies the feeling of being hemmed in, as though the walls themselves are closing in on the characters and the audience alike.

The intimacy of watching a play remained intact throughout the screening, the digitised version provided more accessibility for the audience and the play when it comes to archiving and preserving art. While the play was categorised as “absurdist,” it evoked reflections on the dystopian nature of modern interpretations of “freedom of speech.” Amidst the skewed semblance of hope, a genuine connection with the performers emerged, emphasising how the concept of “hope” has been diluted. “Age of Prison,” with its blend of optimism and surrealism, provides a poignant exploration of speech and its constrained evolution in contemporary society.

Words by Esha Aphale.

Image courtesy The Age of Prison.