There’s somewhat of a collective anxiety in the way the world is hurtling towards the future; a social agreement on the value of gauging the act of living in gain and loss. Be it investment and career decisions, or the way in which we spend our time off on the weekend- there’s a general sense of measuring worth for every second of everyday. There’s value in such a worldview, but there is also loss. And the aspect of humanity that has suffered the most from it is the small moments; small investments of time and heart that a slower, calmer society allows.

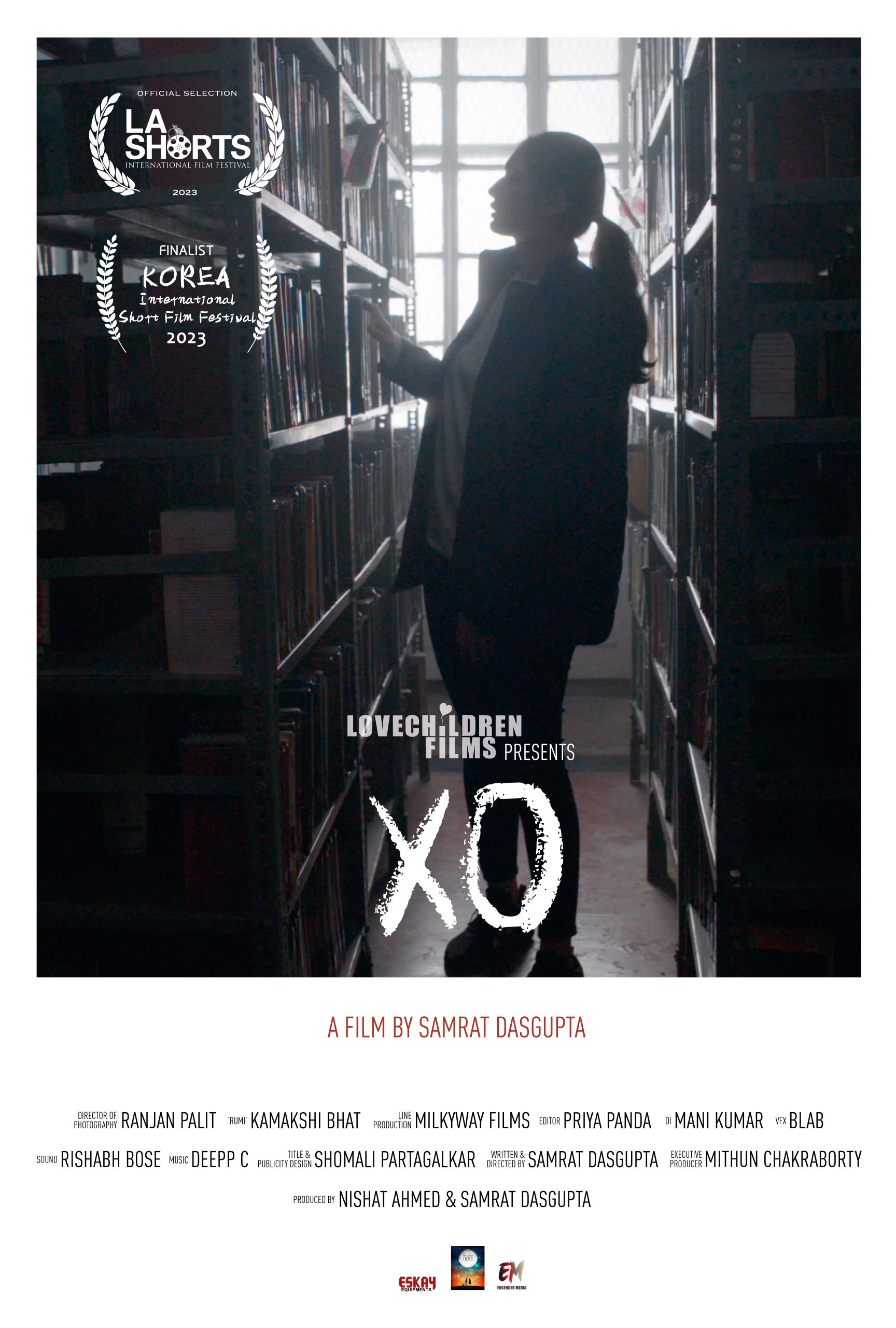

I like to call these little pockets of time ‘glimmers’- an open conversation with a stranger you’re sitting beside on public transport, a wrinkled hand that you held while guiding someone new in town who asked you for directions, a pen pal, and a small game of tic-tac-toe. The interesting thing about a country like India though, is that it allows you to time travel- where a calmer past coexists with a rapid present as we move geographies and cultural backgrounds. And XO, a short film devoid of screens and traffic noise and factory smoke, explores that little intersection of nostalgia and the present that can inhabit a small city of Bengal.

Stills from the movie XO.

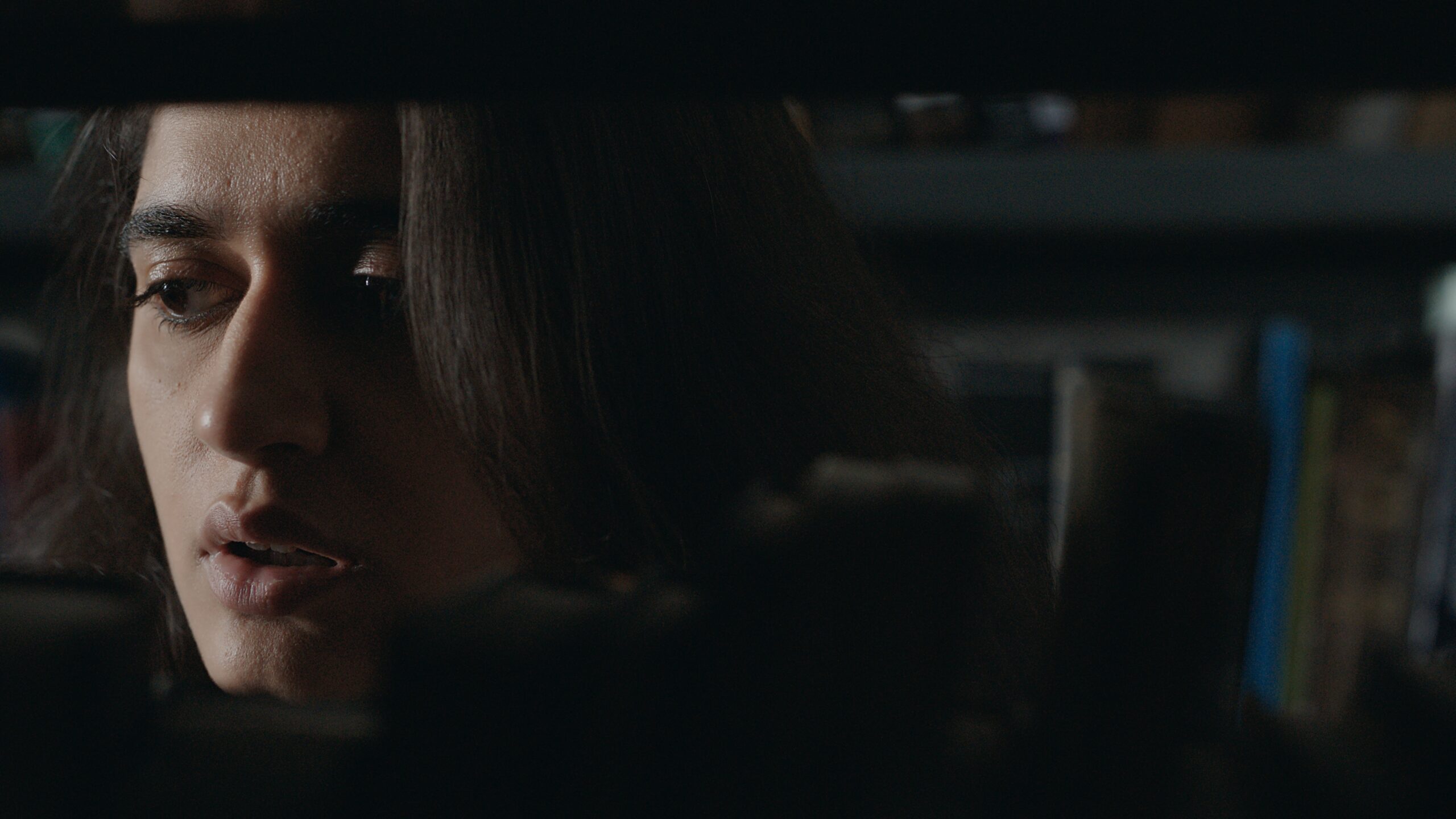

Now, one would be right to assume that these ‘glimmers’, as we will call them, are sometimes fleeting while at other times instigators of the opening of a valve inside you that you hadn’t even realized was jammed. Samrat Dasgupta’s XO talks about the potential of a glimmer to do the latter. With a runtime of about twenty-five minutes, XO stretches time as if it was a 10-year-old on summer vacation, while encapsulating days long events into the narrative. And it does so through quietness. That is, there’s barely any dialogue that gives a verbal language to Rumi and her thoughts and feelings and minutes are spent on a scene where almost nothing happens, but a small twitch on Rumi’s face or a small look of longing she attains as she reads Neruda’s 20 Love Poems on her commute. Dasgupta’s film is defined by these moments and silences, which have been personified intricately in Kamakshi Bhat’s Rumi. It’s a film rooted in nostalgia, inhabited by a particular kind of slowness that an individual finds stuck on cobwebs in the back shelves of old libraries, the kind of home someone with a pre-smartclass childhood can taste in the smell of chalk.

Stills from the movie XO.

The subject matter of XO is of a subtle nature, one that demands your full attention and immersivity, and requests you to leave any expectations outside. It creates a trajectory for feeling- loneliness, desire, connection, and loss. So that once the trajectory is completed by both Rumi and the viewer, they’re left with a lighter heart and a desire to skip next time they walk. Rumi’s isolation sets the tone for the beginning, her hesitation to give in to her desire to participate in a game of Tic-Tac-Toe with a mysterious stranger in the corner of an old, dilapidated library, indicating to a guarded and closed-off psyche. It is her decision to play anyway that sets things in motion. There’s a slight swagger in her walk now, a smile on her face and something that excites her. There’s a presence, and she slowly starts creating space for it inside her, one cross at a time. And when that presence disappers, just as suddenly as it came in, Rumi’s loss becomes the viewer’s loss. And because she feels it- she has the time to you see; her world is slower- the viewer feels it too. It is this space to feel that we forget to give ourselves, because of how measured our approach to our time is. It is this space that XO creates for the viewer, as an unexpected gift.

Stills from the movie XO.

The Indian New Wave was born and perfected by Bengali cinema, and XO is reminiscent of that tradition of somberness; that realistic approach to storytelling that perhaps began with filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak, and which has been since carried on, added to, and dissected by many filmmakers since. And even though the socio-political themes and drama of New Wave cinema is not included in Dasgupta’s subject matter, the narrative and visual grammar echoes that reality induced, mundane representation of life. Which is why seeing Ranjan Palit’s name in the cinematography section of this film felt the same as fitting the square peg in the square hole. Palit is a master at visualizing feelings and has a roster to prove it. With films like Celluloid Man, Saat Khoon Maaf, and The Texture of Loss done and dusted, Palit’s work in XO at the age of 70 is just another feather in a cap that has started looking more bird and less cap at this point.

XO reached the final selections of the Korea International Short Film Festival 2023, and is an Official Selection in the LA Shorts International Film Festival, 2023. As you watch Rumi pick up the chalk and make another ‘x’ on the rusty shelf of the library, an old and scratchy song might play in your head. For me, it was Kishore Kumar’s ‘Na tum hume jaano, Na hum tume jaane’, and I was filled with a sense of calm. I wonder which song plays in yours, reader.

Words by Mansi Arora

Images Courtesy of Lovechildren Films.