When thinking of food as performance, ‘around’ and ‘with’ the entity of time, one looks beyond the difference between how long it takes for something to ‘cook’ against being ‘eaten’. Interest lies in how the food demands that one spend a certain amount of time with it; to extract not physical but, for the lack of a better word, metaphysical pleasures. The gratification is not limited to flavour enhanced by prolonged proximity with aromas and techniques, but in other ‘truths’ being made evident which may have nothing to do with gastronomy.

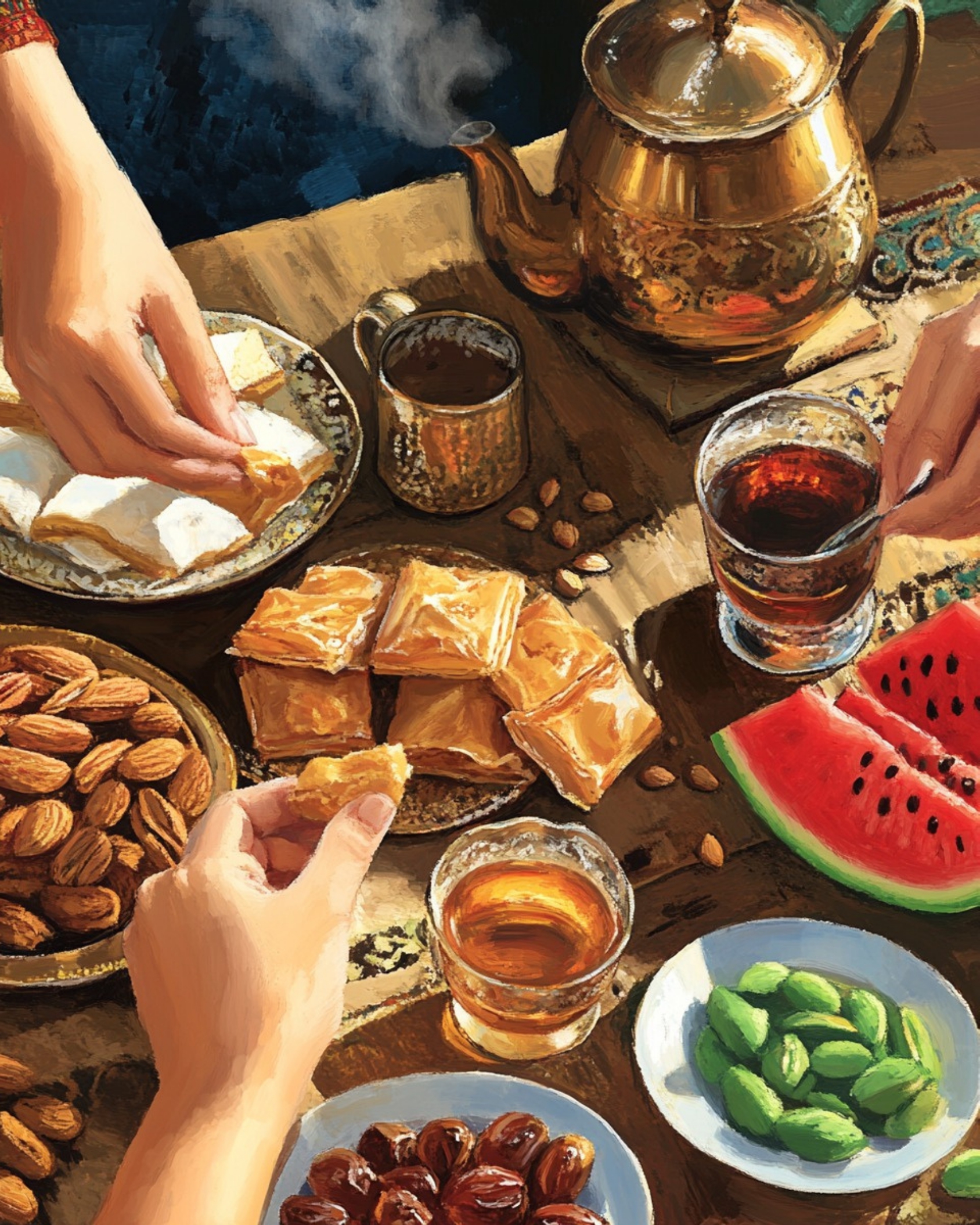

For instance, Iranian ajîl-e Moshkel-goshâ or ‘problem-solving nuts’ is a trail mix eaten by friends and family on the Yalda or Chellah night. The more they talk, the more they eat. At the end of this long, winter solstice night, the community feels closer — many of its problems seem resolved. In Iran, this is accompanied by recitation from the Divan-e-Hafiz and Shahnameh. All this could be done sans nuts and seeds, but something would be lost from the experience — and it won’t be flavor or nutrition.

The special experiences of Yalda — conversations over nuts and seeds.

One might think a seed’s destiny as something edible will be fulfilled only after a significant passage of time; but as Jenny Lau puts it in Chewing on Seeds, “[Any] seed bearing agricultural society is also a seed-eating culture.” Such practices are built on the premise of delay, prolongment, boredom, thwarting instant gratification, and a general manipulation of the experience of time.

We have memories of splitting open melon or sunflower seeds during hot summer afternoons. What impulse pushed us into the hard labour of using tongue and teeth to get to the kernel until our jaws ached? What significance did it hold for otherwise prim and proper grandmas? With foods like these, a tear opens in the fabric of time. One lets go of the mechanical way of being around each other and savours the company more than the snack.

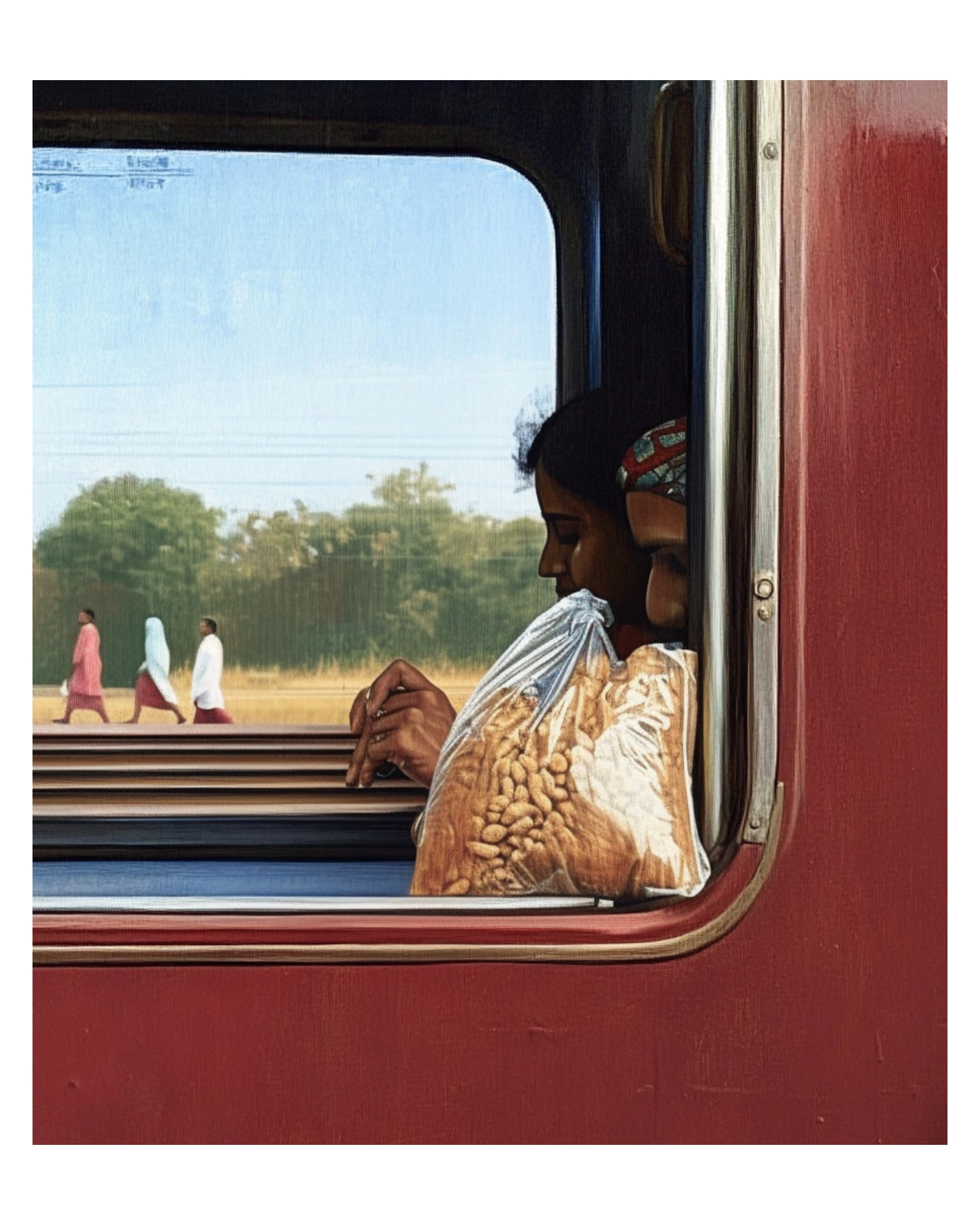

When cracking peanuts with your family on a cosy winter night, the dwindling stock, as shells pile higher, and kernels are consumed, does not give the satisfaction of a meal completed. It tugs at one’s heart, in a nostalgic way, marking the time of separation. Once the nuts are eaten, it is time to disperse. While roasted peanuts are delicious, you would often hear people going for ones still in shells because ‘What is the point if you don’t get to crack them?’ For North Indians, the peanut skin and husks are a core memory. One could not take a train to an ancestral village without spotting mounds in some corner or the other of the compartment. The scenery of green plains passes by and peanuts add to the contemplative charm of the experience. It is something to do without the pressure of accomplishing anything. At the end of a pack, you may find yourself hungrier than when you started!

The makings of a complete travel experience — bagful of peanuts, ready to be shelled.

The urban equivalent of similar experience would be the popcorn while watching a movie, or chewing gum while riding the subway. It is an unspoken rule to not have a proper meal in a cinema hall. Rather build an appetite for the usual ‘movie and dinner’. Similarly, the commute feels faster as long as your mouth keeps chewing on gummy nothingness. One almost understands a movie better while munching on something. But this ‘something’ must not concentrate the cognitive power upon itself too much. It should be ‘food’ enough for the mouth but leave the mind free. Candy floss also plays with impressions of time. As you watch the pink, glossy, sugar webs spin round and round and become a wisp, then a thread and eventually a cloud; mere minutes may have passed but the swirling spectacle makes it seem longer. As you put it in your mouth, it dissolves within seconds. A sugary taste is left behind, but the moment is so ephemeral that if it were not for the aftertaste, you would think it did not happen at all. That time has not passed and nothing has occurred. You can feel the absence of time in the presence of the act.

Such food acts are universal and timeless. Ching Ching Tan, a lecturer in Communication Studies at San Jose University writes about the V-shaped chip which develops between the two front teeth of many people in China over years of cracking seeds. In Oh, Small Peanuts she connects the habit or hobby to healthier snacking, controlling anxiety, and an excuse to get together. Most of all she connects it to wanting to be close to family and to her separation from her homeland.

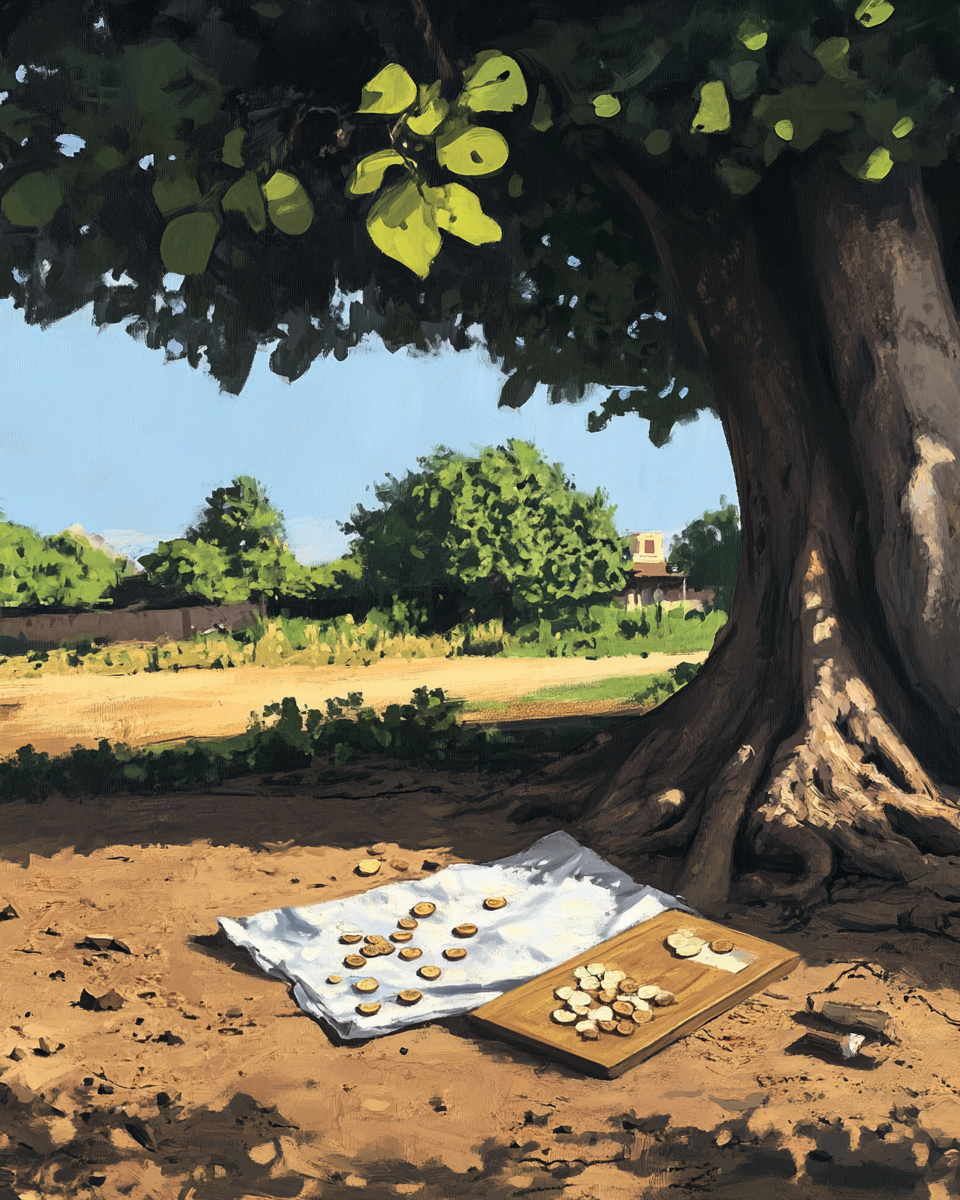

The sweet accompaniment of time with our favourite foods — popcorn at the theatre, and the patient drying of fruit under the sun.

The Russian habit of eating semechki or sunflower seeds has also taken curious cultural turns throughout the centuries. Introduced by Peter the Great in 1698, the habit took root. Even today, sombre as it is, Russian soldiers carry sunflower seeds in their pockets to control anxiety and kill time. At one point, the Russian intelligentsia despised the Bolshevik soldiers for spitting seeds in the streets of St. Petersburg; an act of callousness against ‘old Russian values’. In Turkey, these seeds are called fakir kokaini or the ‘poor man’s cocaine’. The repetitive chewing and spitting creates a trance like state wherein it is easier to forget the troubles of life. The cyclical nature of the act, the delay of gratification, the simplicity of the snack and the rebellion of being at leisure makes these ‘food acts’ stand apart from the usual flow of nourishing oneself. The time spent, in any concrete way, may seem unproductive, but there is a depth of history which time-pass foods bring to daily routines.

As I write, I carelessly chew on nuts. Dorothy Parker once said, “I hate writing, but I love having written.” I could not imagine writing without the motion, anticipation, and pleasure of aimless munching.

Words by Ayesha Suhail.

Feature illustration by Ila Shree.