At Eudaemon, Manik Handa is making formal men’s clothing with the precision of a German with his cars, an Englishman with bureaucracy or an Italian with wine. For him, ‘time’ does not supersede ‘perfection’, which is why a single shirt can take up to three weeks to deliver. Even after that, if a customer is unhappy, they are willing to apologise and begin again.

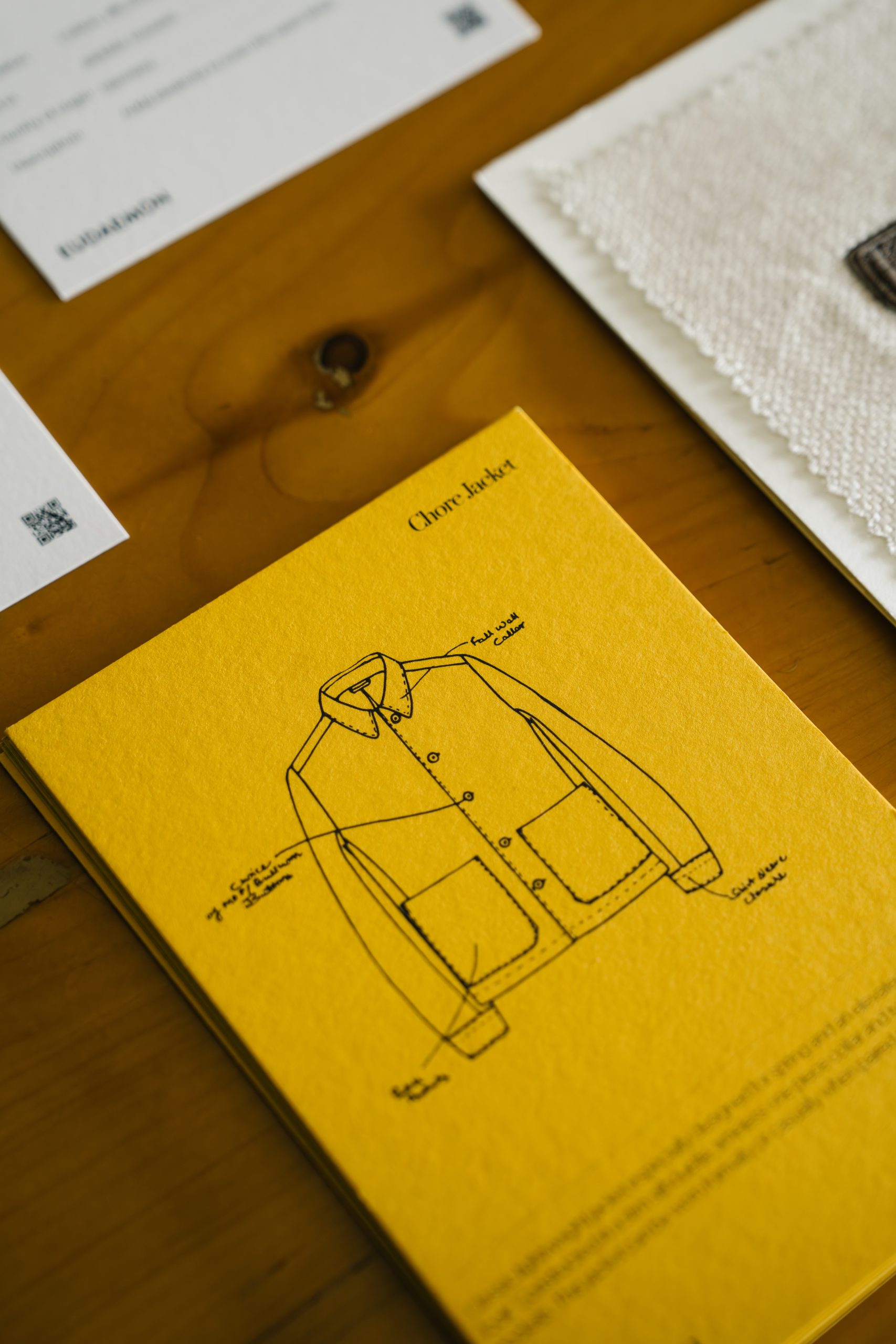

When a client walks into the open concept, 3000 sqft store in Gurgaon, they are privy to the cutting, sewing, measuring of fabrics, details on cuffs, waists, buttons, and seams being done by a team of 25 craftsmen. The brick floored space with curtained, easy-to-access compartments, allow both the makers and the customers to participate in the ultimate experience of customisation. As Manik puts it, “It’s like a live kitchen,” however you can shop only after booking an appointment, there are no racks of clothing, and everything is bespoke, handmade and personalised.

Clothes are tailored to correspond with occasion, personal choices (tempered by cautionary expertise) and personality. Manik shares that, “For the first meeting the client is with us for two or three hours. We usually take the measurements, and try to understand what that person enjoys, what they are like; because I think if you have the right attitude, you will be able to carry any garment. Once the person feels these people understand what I want they don’t want to go anywhere else.”

A brick-floored atelier with curtained compartments, designed for a seamless bespoke experience — where craftsmanship comes to life, one appointment at a time

This trust in the brand’s services is further cemented by Manik’s curious injunction of ‘Don’t Shop’. As he explains it, “There are customers who tend to order a lot. They will say ‘Give me 20 shirts.’ Now, if one shirt goes wrong, you can absorb the cost. If 20 shirts go wrong, then dude, you’re doomed. So we tell them to go slow, to get only what they need to begin with.” It sounds environmentally conscious but he shies away from the buzzword which ‘sustainability’ has become, making it clear that Eudaemon’s ‘trend-resistant’ philosophy is a consequence of hindsight, “To be frank, the idea was to make something so good that it is hard to part with. Over time we realised that this is the most sustainable way; rather than having a buffet of clothes in a store where 58-60% remain unsold and end up in landfills. We also give a lifelong service wherein we make sure that if an item has to be repurposed we do it. We make classic garments from a total of 30 styles that are reworked based on client preferences. For me, the foundation of sustainability is in fulfilling the value of a thing.”

He worked with Zegna for eight years and owes his initial training in the industry to the company but once he felt the calling to begin his own venture, he quit, “I felt I could envision and deliver a great product which India has a wide space of, it was a great opportunity. Luxury has been a part of the country for centuries; however, men’s wear luxury brands in India can be counted on your fingertips.”

Now that he has created a homegrown Indian brand, how much of its raw and moving elements are Indian? “When we were starting Eudaemon, we went to 30 cities in a span of six months, stayed in different places to find the right factories which could work for us. However, we found all the factories in Italy. I used to travel there often, spend a lot of time on a friend’s couch. This went on for four years, after which we started our own factory here. We do field jackets, we do smart casuals, we do suits, and these are mostly made up of merino wool, the finest is woven in Italy. We work with linens and cottons as well. So there are a few linens and cottons which we source from India. We have also been working with somebody in Auroville who does vegan wool, but it’s all experiments right now. We would love to use more and more things which come from India, but we have not been able to achieve that so far. Our canvases and threads are German. But the artisans are all Indian. I can happily say that our product quality can be compared to any other global clothing brand,” he says.

A team of 25 craftsmen meticulously cuts, sews, and perfects every detail, from cuffs to seams, in plain sight

He believes there is space for at least two more stores; but more stores mean more clients and more orders, with a delivery time of three-eight weeks centralisation and up-skilling of craftsmen is a necessity, a challenge Manik admits they have to confront. He says, “We plan to achieve centralisation in six-nine months and then hopefully we will venture out either to Bombay or to Bangalore or to Delhi. As for making sure that our people are being trained and staying with us, it has not been a problem. Production is at the heart of our work and we treat it accordingly. However, with the centralised production facility we intend to start a school of sorts where we are training people to ensure a reduced delivery time of 10 days and kick-ass quality.”

When talking of profits and widening the customer base via catering to women or getting into Indian wear, Manik has the same response: “It is challenging, all the notions people in this industry have about profit and mass production in the shortest amount of time possible, but for me, there are two ways of doing it. Either you do ‘quantity’ as fast as possible and sell it to as many people or you do ‘quality’. We never had a collection before but if you look at the website, we started last year. We are very good at saying ‘this fabric goes extremely well with this style’, so when customers see that, they can envision it better.” Although, he jokingly admits to women wearing Eudaemon jackets which they have poached from their partners and looking better in them; it points to the increasingly androgynous clothing trends growing internationally.

If Eudaemon is moving slow compared to fast fashion, it is also lasting long. Its competition is global, its client is cosmopolitan but its roots and craftsmanship are Indian. Truly, as the brand states, ‘God is in the details’.

Words by Ayesha Suhail.

Images courtesy Ashish Negi for Svasa Life.