Urbs Prima In Indis, translates from Latin to ‘The First City in India’. Bombay then, Mumbai now.

Bombay, the city of seven islands, boasts of a captivating history. Bequeathed to the British as a part of the royal dowry from the Portuguese Catarina de Bragança when she married King Charles II of England.

With seven islands of Bombay slowly amalgamating into one, Bombay, from a native town, slowly grew into a commercial city, as trade and commerce boomed.

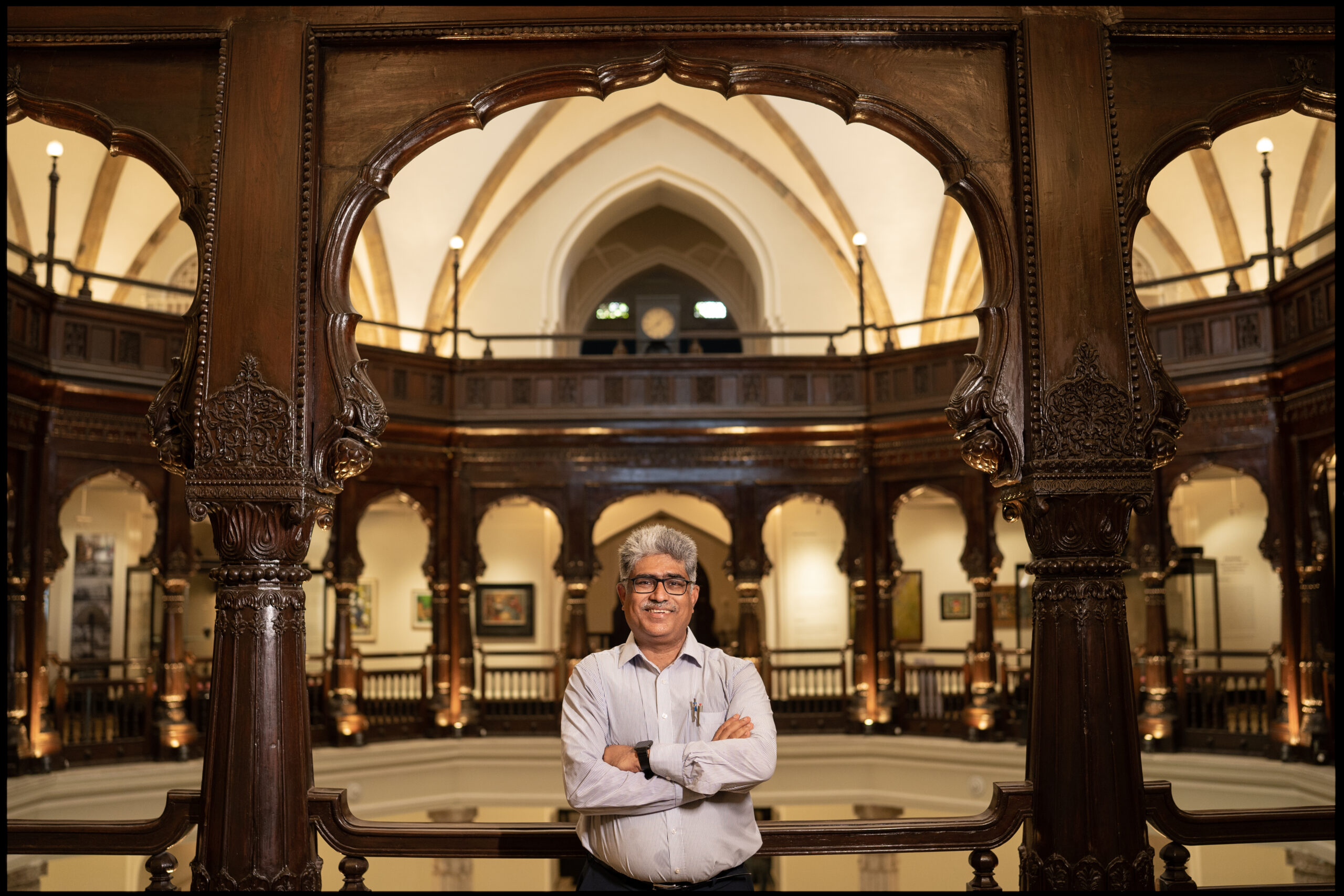

In conversation with restoration architect Vikas Dilawari, he traces the origins of the city and travels back to a Bombay that was, telling stories of the city from over a hundred years ago.

“Bombay is a hallmark city. When one came from England by streamer, Istanbul was the first city to have a blend of architectural styles of the West and East. Beyond the Suez Canal, Bombay was the first at the time to be at power with international cities. The finest city East of Suez.”

Vikas Dilawari at the Prince of Wales Museum, also known as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalya

Being a historian, from my perspective, Bombay remains one of the most interesting gothic cities in India, with layers of architectural styles talking about different time periods lived. The title of ‘City of Domes’ rightly describes Bombay’s old skyline, with Neo-Classical, Gothic Revival, Indo-Saracenic, and Art-Deco styles of architecture marking its cityscape.

Talking about the evolution of architecture in the city, Dilawari explains, “Before the setting of the Empire, with the East India Company, the architecture was subdued. Neoclassical architecture, trying to adapt to the climate using pediments, as seen in the Town hall. After mutiny, Bombay was under the Crown and the architectural language deliberately chosen was Gothic Revival.

Interiors of Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum

The skyline of the city was first marked with towers, turrets and spires. Victoria Terminus was the first building to have a dome, after which domes featured in most of the important buildings.

Then came the Art-Deco movement, and domes lost their place to a more modern architectural movement.”

Over the last three decades, Bombay has seen a decline of heritage structures, many of which have crumbled with time, while others are given a new life through conservation architecture. A revival to the city’s old glory is underway, with heritage conservation slowly coming to the forefront. Many iconic institutions and historic structures have been restored to their former splendour by conservation architects striving to preserve the heritage of the city.

Having restored 50 heritage buildings in the city, Dilawari talks to me about how conservation is all about sensitivity. “In conservation we follow the rule of minimum intervention, and aim to respect the vision and creation of the architect of the edifice.

The idea is to keep our egos to the minimum, and bring back to life what the original architect has created, with minimum modifications to original structures. We need to respect historicity and the architect’s inspiration whilst integrating present day amenities, without disturbing the original architecture and interior details that give it its character.

The biggest compliment to me sometimes is…what have you done?”

The erstwhile emblem of the BDL Museum which was formerly the Victoria & Albert Museum

Indo Saracenic meets Art Deco at the Prince of Wales Museum

Most recently, the Victorian and Art-Deco Ensembles of Bombay were declared UNESCO World Heritage sites. These ensembles entail a collection of nineteenth century Gothic Revival public buildings and twentieth century Art-Deco private buildings in the Fort precinct in Bombay. A walk through this area of the city can take you back in time, demonstrating how the architects have restored these edifices without taking away their original character.

Speaking about restoration, Diwalari sheds light on three decades of his work, and the challenges he has encountered. A conservation journey that began in 1995, Dilawari believes in quality over quantity. His first project was restoring the interiors of the American Express Bank housed in the Oriental Buildings in Fort. Then came the Amarchand Mansion, where he restored an entire wing painstakingly. This was followed by the Rajabai Clock tower at the Bombay University and many other notable structures of the city.

Mint and gold walls, artefacts and chandeliers at Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum

On asking him about the most difficult heritage structure he has restored, Dilawari talks about the fire-damaged Corporation Hall of the BMC Headquarters in Fort.

”With keen attention to detail, we revived the damaged building using the art of gilding with real gold. The original colour scheme revealed upon scraping layers was mint green and gold, as seen in a lot of Victorian buildings of the time. The hall was successfully restored to its former glory in 2002.

This was the most challenging project, but the completed work was applauded and recognised worldwide. The greatest complement I received was from the team who restored the Windsor Castle in England which had burned down with fire as well. Their team appreciated our work greatly and was truly amazed at how we completed this work at one third the cost.”

Having restored the two most significant museums in the city, Bhau Daji Lad Museum and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, celebrating 150 years and 100 years respectively, Diwalari goes on to talk to me about his journey through museum restoration, and his research methodology.

Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum

“The BDL Museum is a brilliant example of passion for conservation. Tasneem Zakaria Mehta has been instrumental in the museum’s restoration from then till date. In 2003, a team of us – Mrs. Mehta (BDL), Mrs. Bajaj (sponsor), Ms. Desai (consultant) and I went on an educational program to see around 20 museums in the UK.”

It’s interesting to note that the Bhau Daji Lad Museum was the former Victoria and Albert Museum in Bombay. “We studied the museum inside out. Scraping layers of paint, we found the quintessential Victorian museum green and gold. The museum was embellished as it was done originally, with gold gilding.

It was my first project of comprehensive conversation from the inside out, and it is the only building to have won the UNESCO award of Excellence in Bombay. “

Another structure that he has beautifully restored, in my opinion, is the Flora fountain – which in many ways is considered the symbol of Bombay. At the heart of the city, the stone statue of Roman goddess Flora shines with her spirit of flowers of fertility.

At the junction of five main streets beyond the fort walls of the Bombay Castle that once stood, the fountain stands at the Hutatma Chowk (the Marty’s square) at the centre of Gothic Bombay.

Dome at the Prince of Wales Museum

An anonymous cricketeer writes about Flora,

“The Centres of the world are well etched in the mind: the New York City’s Time Square and the Paris’ Champs-Èlysées, London’s Piccadilly Circus. Even now I feel a curious magic about Bombay’s Flora Fountain. We called it the heart of the city and so it was.”

Diwalari considers the restoration of Flora Fountain, a pivotal project in his restoration career.

“The water engineering proved to be the most challenging in the conservation process. We systematically opened areas to understand the flow of water, and restored it to a fully functional fountain.

While working on the railing and stone paving, we found tram tracks, which we decided to leave exposed. In my opinion it is important to conserve that kind of history, as the coming generations wouldn’t know what trams are and how the city once functioned,” he finishes.

Bombay remains a city of curious histories, that are unravelled layer by layer, with every restoration. The rich cultural heritage of the city breathes through its architecture. The city structures tell stories of every decade that is lived, and restoration brings back these stories, giving them life and meaning, in an ever-changing metropolis.

Words by Anushka Gupta

Photographs by Aditya Pandey